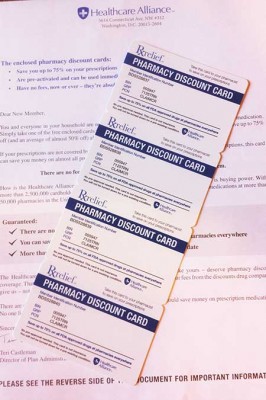

The Rxrelief discount cards. The letter suggests giving extra cards to “anyone who could save money on prescription medications.”

Obamacare and its muddying of the medical-cost landscape offers newly fertile ground for advocates, entrepreneurs, and crooks.

So against that backdrop of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, one of our staffers received an envelope—unsolicited—in the mail bearing resident code “HB-6357-14294” and containing “pharmacy discount cards” and a letter welcoming her as a new member of Healthcare Alliance. It’s one of those things that almost require you to examine with jaundiced eyes. The cards, which reportedly can open the door to discounts up to 75 percent, were “pre-activated”—not a surprise since the unsought membership itself came pre-activated—and could be used immediately. At least the program didn’t ask for any money up front, and the letter says the cards “have no fees, now or ever—they’re absolutely free.”

The letter looked reasonably official, and while you might mistake it for something important from your own health insurer, it still had a sufficiently commercial edge that you wouldn’t mistake it for a government or genuine do-not-ignore-me document. (Oh, that I could say that of some of the junk mail I got after re-financing.) And the four cards from “Rxrelief” enclosed, each featuring a presumably unique membership identification number along with alphanumeric identifiers for “BIN,” “GRP,” and “PCN,” all suggest some official rigor is involved.

And yet … I expect most Americans, barring those still awaiting Nigerian fortunes, would echo my wariness about the Healthcare Alliance, as a little chat with my good friend Mr. Google bore out. As I typed in “healthcare all…” autofill suggested “healthcare alliance pharmacy discount card is it a scam” among other choices.

Spoiler alert: it’s not. But the words “skeevy” and “shady” do come up in online forum conversations about the cards, and so too does the not-exactly-ringing endorsement of “it isn’t overtly evil.” Online forums, as this exercise demonstrated, are also giant echo chambers, where one person’s suspicions instantly morph into the next person’s facts, and concerns, say about personal privacy, lead to baseless calls for a class-action suit.

At the same time, some posters say they’ve used the cards and are pleased saving money, but it’s a rough neighborhood when people are aroused. After “Darla K” posted this at the Topix forum for Lexington, Kentucky:

I have used the RxRelief Card. Not in Kentucky, but in New York. It saved me almost 50 percent on eye drops. I was skeptical too, so I e-mailed customer service. Someone got back to me right away and told me it was no strings attached, totally free, etc.

I’ve shared the card with friends too, and all have had a positive experience. If they have our personal information, I haven’t noticed any effects of that.

“EEE” responded, “Wow, you sound like you work for RXRelief. Caveat Emptor. Big Time” while “Cele” reported, “I’ve been checking other sites. This ‘Darla’ pops up on ALL of them.”

A little more sophisticated digging does no favors for the program. The D.C. address for the Healthcare Alliance actually leads to a mail drop at a UPS store on Connecticut Avenue just south of Chevy Chase Circle. Lest that sound a little questionable, rest assured that this particular UPS Store is a hotbed of medical-related services, including the Mesothelioma Victims Center at #138 (also the home of the Nursing Home Complaint Center!) and the National Council on Interpreting in Health Care at #119.

While the maildrop is in D.C., the business itself—which operates under the names Healthcare Alliance, Rxrelief, and Script Relief LLC—is located in New York City. Dave Lieber, who writes the Watchdog column at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, phoned the company when he received a similar card last fall. He talked to Michael Loeb—this guy—in NYC, who explained about the maildrop, “It’s very convenient to get reply mail. We can’t in our New York office handle any reply mail directly. So we get it there, and it’s forwarded to us.” Can’t fault him for that; after all, I have a P.O. box, although oddly enough it’s in the same city I’m in.

The site scambook.com lists one complaint about the company, but the complaint echoes what I’ve written here: an unsolicited offer came in the mail. The same with Better Business Bureaus in various locales: a few complaints in the last two years, but mostly because something mysterious but quasi-official-looking arrived. I talked to my state’s Office of the Attorney General and the Federal Trade Commission, and after confirming that the program wasn’t touting itself as insurance, nobody at either office had anything untoward to report.

So I called Healthcare Alliance/Rxrelief/Script Relief, and while I’d expected to fight my way up the chain to eventually get somebody like Loeb to open up, instead I got a nonchalant but helpful customer service rep who identified herself as Desiree Smith.

How does the company make any money? They get a small amount, like a processing fee, from pharmaceutical companies when the cards are used; they’re aligned with this company to provide the discount the user receives.

Where are the cards accepted? At pharmacies the company has contracted with, and those negotiations also set the discount.

Who gets the cards? Some people opt to receive them, but others are drawn from sources (i.e. mailing lists) that identify likely users for the solicitation.

How many people use the cards? Smith said there are 800,000 cardholders, although the original letter says “more than 2,500,000 cardholders have saved $175,000,000 to date.” That comes to, by the way, $70 per cardholder, although I question whether a cardholder—I’m holding one now—equates to a card user.

And lastly, what do you do with my personal information? There is none – the cards are “completely anonymous” and the ID number is generic.

Hirka T’Bawa, a charter member at the StraightDope.com message board, explained the set-up from a pharmacy’s perspective:

As far as the pharmacy is concerned, you can use those cards just like an insurance card, we process them the exact same way. They give you whatever discount has been negotiated by the PBM (Pharmacy Benefits Manager). For most drugs and pharmacies, it would probably save you a little money from the cash price.

Or as forum moderator “stkitt” at HealingWell.com wrote two years ago:

The card works similar to insurance companies. It’s like a large buying group. Card holders pay pretty close to what the large insurance companies pay. The savings comes from the drug stores.

In fact, there’s a thriving little business model built on the cards, some that have a government imprimatur, some from pharma companies, some from nonprofits, and some from scrappy companies like Rxrelief. And if you’re not satisfied with the process or the savings, and people with insurance tend to already get cheaper meds already, don’t use the card.

I get discount offers all the time from third parties, offers that don’t make my antennae twitch. Sitting to my right, for example, is a flier for employee discounts from ADP, which handles our payroll. Oddly, while the sponsor for the discounts in this case is a health plan, CaliforniaChoice, the discounts are for things like amusement parks, dry cleaning, and Embassy Suites Anaheim.

So everything’s hunky-dory with these cards? Not necessarily. In determining that the FTC didn’t have a beef with these guys, the agency offered some examples of past discount card programs that had been scams or crossed a legal line somewhere.

Since I started writing this post earlier in the week, I received a glossy package from my new medical group telling me who my new primary care provider is and what wonders his practice offers me. Except I haven’t changed my provider and I don’t know yet if this is a scam or an honest mistake. And I routinely get a lot of solicitations—I’m looking at you, United of Omaha Life Insurance Company, and the FINAL Notification you sent both to my home and my P.O. box—that cross from hopeful to skeevy.

So I’m sticking to EEE’s advice. Caveat Emptor. Big Time.