It can be hard sometimes to visualize an epidemic—especially one as historically big and devastating as HIV. That’s why some researchers have turned to maps, which can illuminate links between policy and public-health outcomes in surprising ways.

Patrick Sullivan is a professor of epidemiology at Emory University who previously worked in HIV/AIDS surveillance for more than a decade at the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). He can speak at length about the factors that have made the HIV epidemic difficult to address in the U.S.—including the challenges many people face accessing high-quality care in remote areas, the stigma many HIV-positive people still face, and the roles of income, poverty, and race in preventing and treating HIV.

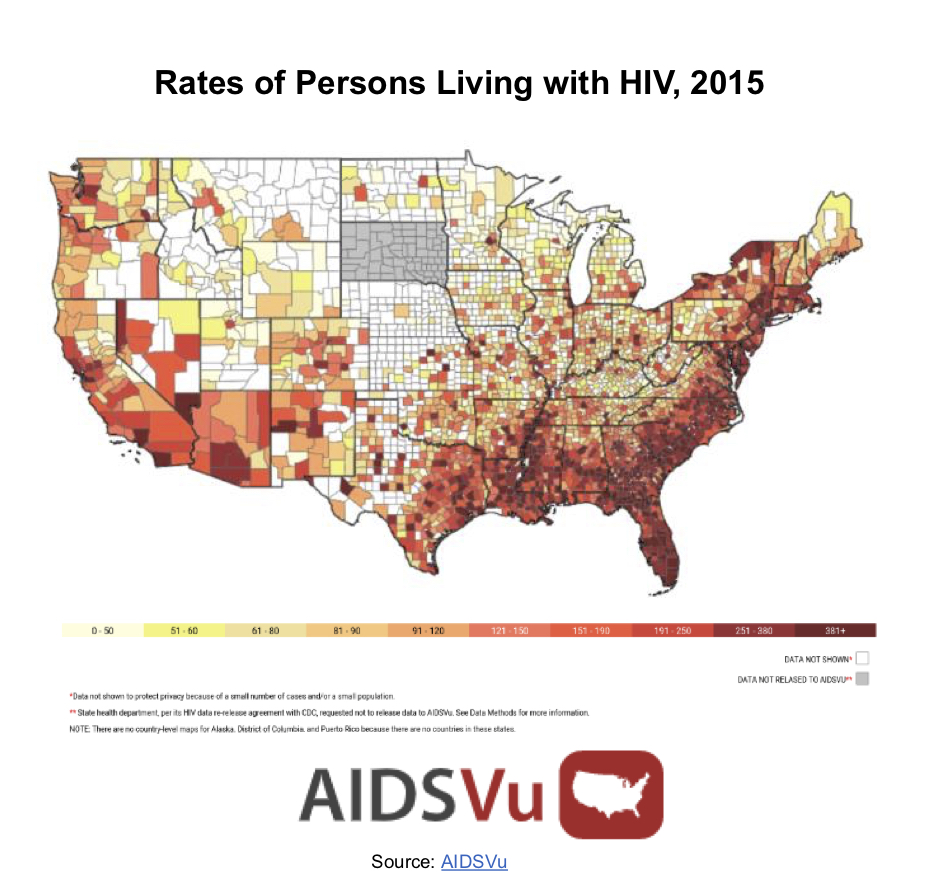

But then he says, “I’m going to show you a map.” Sullivan pulls up an interactive map from AIDSVu, an HIV mapping project he leads, and zeroes in on his home city, Atlanta. He points to the districts around the downtown area, colored in a deep shade of purple, which means a high rate of new HIV infections. This area is home to much of Atlanta’s gay community, as well as many African Americans and lower-income residents—communities that are often at higher risk for HIV.

“Every time we have a new HIV diagnosis, that is an infection that we failed to avert,” Sullivan says. He overlays a map of clinics that offer PrEP, a daily pill that prevents HIV infections. Only one of the clinics is located within the deep-purple zone. The rest of the clinics are located in more affluent regions that have lower rates of new infections.

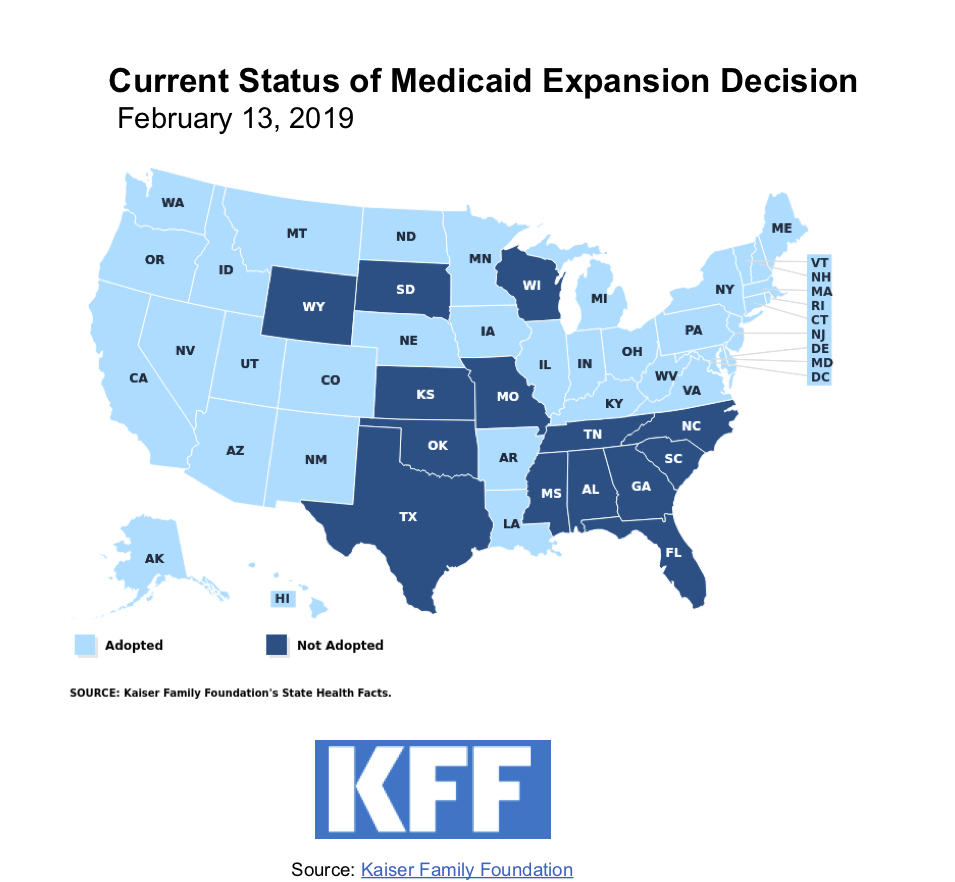

Another telling map from AIDSVu shows a sweep of red dots signifying new infections across the U.S., particularly concentrated in the American South, laid next to a map of states that declined to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. The swaths of color are largely the same.

These maps tell a story about HIV in America that words alone cannot. And much of that story takes place in the South. Home to one-third of Americans, the South accounts for more than half of all new HIV infections. Last month, the CDC released its annual HIV Prevention Progress Report, which looks at the steps we’ve made and the challenges still holding us back. According to the report, “persons residing in the southern United States” are a significant group of people at increased risk of acquiring HIV—along with people of color and men who have sex with men.

The reasons for the South’s disproportionate burden are complicated. Southerners tend to have access to fewer doctors, they travel greater distances for medical care, they have lower rates of health literacy and higher rates of poverty, and they often experience racism inside and outside the health-care system.

And then there’s the widespread lack of insurance.

Nine of the 14 states that have not yet adopted Medicaid expansion are found in the South, and the region is home to five of the seven states in the U.S.—Texas, Oklahoma, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi—where 12 percent or more of the population is uninsured. These are also many of the states that have seen a significant rise in new HIV infections in recent years.

HIV isn’t rising in the South because people there don’t know how or why to be tested for it, says Chris Beyrer, the Desmond M. Tutu Professor of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University and a past president of the International AIDS Society. Rather, he says, “It’s a function of the refusal of the red-state political leadership to expand Medicaid through the ACA.”

“It is so remarkable how the map of HIV has changed,” Beyrer says. In the early years of the epidemic, he points out, the virus swept large coastal cities. “Now the places we’re really most concerned about are East Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida. There, what you’re seeing is many more people living with the virus untreated, very, very low rates of PrEP access and PrEP uptake, and real problems in health disparities that are structural and social.”

In his State of the Union address on February 5th, President Donald Trump made a pledge to halt the HIV/AIDS epidemic by 2030.

To some, this was a surprising statement from a president who’d once asked whether HIV and HPV were the same thing. But the Department of Health and Human Services has been rolling out its plan to focus on the counties and cities that bear the overwhelming burden of HIV. The initiative aims to cut new infections by 75 percent in the first five years, and by 90 percent in the next decade.

More than half of all new infections in the U.S. happen in just 48 counties, as well as the District of Columbia and San Juan, Puerto Rico. The Trump administration plans to focus on these hotspots of new infections, alongside seven states with comparatively high rates of HIV in rural areas: Oklahoma, Missouri, Kentucky, Arkansas, Alabama, South Carolina, and Mississippi.

The administration’s new initiative will focus on diagnosing people with HIV and getting them on medications to help them manage their own health and become virtually non-infectious, while also helping those who are HIV-negative but at risk of contracting the virus get access to PrEP, the daily pill that dramatically reduces the chance of infection.

“It really is the right approach to addressing the HIV epidemic,” says Jennifer Kates, vice president and director of global health and HIV policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, who helped create the AIDSVu maps that cross-reference states that declined Medicaid expansion with maps of new HIV infections.

(Photo: Kaiser Family Foundation)

“It’s certainly not going to be an easy path,” Kates says. “The factors that are at play in the South do make it more complicated—and also it’s the region that needs [help] the most.”

In other words, the administration’s plan is a good start. But it can’t end there, experts say.

“There has long been bipartisan support around HIV/AIDS, and that appears to be continuing. And that is extremely welcome,” Beyrer says. “What there has not been support for, in a bipartisan fashion, is expanding health care for low-income and working Americans.”

In the same budget where the president requested funding for the new HIV initiative, he also made deep cuts to Medicaid and other social programs.

Medicaid is the largest source of coverage for people living with HIV. In 2014, half of all Americans living with HIV were on Medicaid or Medicare. Meanwhile, 14 percent, or about one in seven HIV-positive people, had no insurance at all, according to Kaiser.

Health insurance, whether privately or publicly funded, is “critical” to addressing the epidemic, Emory’s Patrick Sullivan says.

Yet just two weeks ago, the Trump administration argued that the ACA—which offered about 20 million Americans access to health care that they wouldn’t otherwise have—should be dismantled entirely. For those living with HIV, the ACA’s provision for pre-existing conditions meant the sudden freedom of being able to change jobs and, by extension, insurance plans—something they were terrified of doing before, Beyrer says, because “HIV is the mother of all pre-existing conditions.”

“The attempts to repeal [the ACA] have been enormously frightening,” Beyrer says.

Trump’s plan to lower the rate of infection, Beyrer says, is “long overdue” but “extremely ambitious.” This is the third national plan to combat HIV in the U.S., and neither of the two previous plans met their goals.

“It has been a very stubborn epidemic,” Beyrer says. In the past 10 years, new infections have fallen from about 45,000 a year to about 36,000, he says. Dramatically reducing that number in the next decade will prove very difficult—and may be impossible with simultaneous cuts to Medicaid or the repeal of the ACA.

“That said, Congress has rebuffed the president on all of his budgets so far,” Beyrer notes—and, historically, Congress has been a central force in addressing the HIV epidemic.

“But the Achilles heel is going to be access for those most in need. That’s why the South matters,” Beyrer says. “We have got to do better for the people who are being left behind. Without doing that, we’re not going to achieve these goals.”