Orange-juice containers, newspapers, six-pack cardboard carriers, plastic and paper bags, green compost bins, pill bottles, rain gear, old New Yorker magazines, and running shoes fill Greg Samson’s home, often to waist level. The area around Samson’s stove is clear enough so he can cook turkey patties or fry up some chicken—what he calls the limit of his culinary repertoire. As we talk, he describes a moldering turkey wrapper that had recently been sitting on the countertop for a few days and attracted his attention. “I can’t think of a plausible scenario in which I would need that,” he says.

A few years ago, Samson (not his real name) unplugged his refrigerator. It had, he says, “got out of hand.” He didn’t empty it, and he hasn’t opened it since. I was introduced to Samson because he volunteered to participate anonymously in a research study on hoarding; we meet at his office—he didn’t invite me into his home. In fact, it has been years since he has let in any visitors. But he shows me pictures of the belongings that have encroached upon every inch of his three-bedroom shingled Victorian. I ask him gently if he has thought about getting someone to help him clean out the fridge. “It wasn’t a conscious decision,” he says. “The thing is, there’s stuff that I have to do before we’re ready to deal with the refrigerator. It’s not a logistical thing of getting rid of it. That’s not the problem.” He pauses, thoughtful. “It’s me, in my head.”

Samson first noticed that he had trouble throwing things away when he was an undergraduate at Harvard. He started his freshman year at the precocious age of 15. Like many college-age boys, he was messy, but his belongings were accumulating in a way that, even to him, was out of control: books, papers, and clothes piled up around his dorm room. It took him days longer than anyone else to move out at the end of the school year. “I guess it was a baby hoarding habit forming,” says Samson, a tall, bearded 67-year-old with a ready smile and cheerful blue eyes.

Comic Con on the Couch: Analyzing Superheroes

Is Our Disconnect From Nature a Disorder?

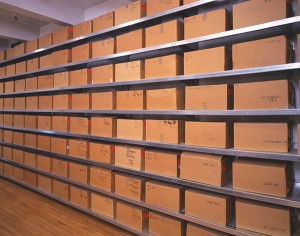

Until recently, not much was known about hoarding behavior. But we have long heard stories. The fourth circle of hell in Dante’s Inferno is reserved for “the hoarders and the wasters.” Dante’s hoarders spend their lives acquiring wealth and material possessions—represented as giant boulders—and are forever doomed to push the crushing weight of the rocks against the opposing force of wasters. In March of 1947, the infamous Collyer brothers died in their Harlem brownstone, trapped beneath 140 tons of detritus—the deaths and the home itself were so gruesome that East Coast firefighters today still use the term Collyers’ Mansion to indicate a home that’s dangerously full of flammable stuff. Andy Warhol was a hoarder; his four-story Upper East Side town house was so jammed with items that the only rooms with paths through them were the kitchen and the bedroom. When he died, in 1987, he left behind 610 cardboard boxes that he called time capsules. But it wasn’t until 1993—just 20 years ago—that Randy Frost, a psychology professor at Smith College, authored the first systematic study of the problem.

In the mid-’90s, Frost began collaborating with Gail Steketee, dean and professor at the Boston University School of Social Work, on hoarding-specific studies as an extension of their research on obsessive-compulsive disorder. They expected to find just a handful of hoarding cases. Instead, they were inundated with calls for help from thousands of families. In researching this story, I was struck by how frequently personal tales of hoarding come up in casual conversation. Friends confided that they feared a family member—a parent, an aunt, a cousin—was a hoarder. In the small office where I work a few days a week, one writer told me at lunch that his mother had been a hoarder; when he and his brother were in college, they could never go home on holiday breaks, because there was no longer any place for them to stay.

Many of us face, to some degree, some disorganization. We struggle with the desire to keep things because we think we may need them later, or because we want to preserve the memories associated with them. We look at the dusty boxes in the back of our attics and promise ourselves that we’ll purge the old golf clubs and outgrown clothes. This all may help explain the national obsession with recent reality-television shows like A&E’s Hoarders and TLC’s Hoarding: Buried Alive.

It turns out that up to an estimated five percent of Americans—nearly 15 million people—suffer from hoarding disorder. “Here is a brand-new disorder, something we didn’t recognize before,” Frost told me. “We know nothing about it. And I’ve been doing this for 20 years. The field is wide open.”

Today, psychologists, neurologists, and other behavioral researchers are looking at genetics and scanning hoarders’ brains. They’re trying to understand how hoarders think, and how to help. In 2011, Frost and Steketee wrote Stuff: Compulsive Hoarding and the Meaning of Things. Later this year they are publishing a new volume of collected research, Oxford Handbook of Hoarding and Acquiring. In May, the Mental Health Association of San Francisco is hosting its 15th Annual International Conference on Hoarding and Cluttering. That same month, the disorder will become its own category in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, also known as DSM-5, the bible of psychiatric diagnoses. A listing in the DSM confers upon a disorder a new legitimacy—and with that comes increased public awareness, more funding for research and treatment, and, for better or worse, a likely uptick in diagnoses.

It took police and workers many days to find each Collyer brother after they died in their overstuffed Harlem home. (PHOTO: PUBLIC DOMAIN)

IN THE 1990s, HOARDING was lumped into the category of obsessive-compulsive disorder because a significant number of OCD patients tended to hoard. But clinical psychologists now think the two are distinct. OCD is a disorder of obsessions: unwanted, intrusive thoughts and urges that you know are irrational and struggle to get rid of—the need to wash your hands every 10 minutes, for example, or the desire to get a pair of shoes lined up “just right” in the hallway. The response to those thoughts and urges? Distress and anxiety. While hoarding can come with some distress and feelings of loss or depression, those thoughts tend to occur only when it comes time to throw things away. In fact, the acquiring phase—the taking of items from a store or garage sale or flea market to one’s home—has been described as pleasant by hoarders. Frost says that no OCD sufferer would feel that way. The use of brain scans to understand OCD and hoarding is in its early days, but research shows that different areas of the brain are associated with each disorder.

Hoarding does appear to be at least partly genetic. Frost thinks the information-processing part may be passed down. Fifty percent of sufferers grow up with a hoarding family member—Greg Samson’s father, for instance, had some hoarding tendencies (and there are the Collyer brothers). Carol Mathews, an associate psychiatry professor and the director of the Obsessive Compulsive Disorders Clinic at the University of California-San Francisco, is studying the family members of people who hoard—family members who do not hoard themselves—to find out whether they also have trouble with sorting and categorizing. “We have very early evidence that they might, although to a lesser degree,” she told me.

Psychologists have also posited that the instinct to collect and hoard may have once had evolutionary advantages—that hoarding could be an adaptive behavior that allowed individuals to survive and achieve reproductive success when competing for limited resources; behaviors like hoarding or excessive cleanliness can be interpreted as an extreme on a continuum of avoiding harm, or of planning for the future. But Frost says evolutionary theory is just that—a theory—and that the hoarding of food, common among many animals, is not something researchers typically see in human hoarding behavior.

Andy Warhol. (PHOTO: COURTESY ANDY WARHOL MUSEUM)

Scientists do agree that the disorder has three (rather obvious) defining characteristics: the excessive acquisition of things that appear to be of little or no value; the inability to discard possessions; and the disorganization of those possessions, which clutter up living spaces and make them impossible to use for their intended purposes.

Though we don’t yet have any data comparing hoarding across cultures, and clinicians have seen cases of hoarding in just about every country, Frost suspects that the disorder is more widespread in the Western world. There is no question that the continuous acquisition of stuff is the backbone of American culture. According to Sandra Stark, of the Peer-Led Hoarding Response Team at the Mental Health Association of San Francisco, “Seventy percent of home-owning Americans cannot park cars in their garages because there’s too much stuff; one in 10 has a storage unit.” More than 20 years after the artist’s death, Matt Wrbican, the archivist at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, had made it though just 19 of the artist’s 610 time capsules. The boxes were filled with everything from restaurant bills and airline utensils to Chubby Checker records and a single mummified human foot from ancient Egypt. In San Francisco alone, nearly $6.5 million is spent by landlords and service agencies each year on hoarding-related issues, which include eviction and the removal of children or the elderly due to health and safety concerns. Hoarding has been identified as a direct contributor to up to six percent of all deaths by house fire.

When Andy Warhol died, his possessions filled 610 boxes, so-called time capsules. (PHOTO: COURTESY ANDY WARHOL MUSEUM)

In Greg Samson’s house, constant vigilance is requited to keep items from covering the old floor heating vents. Samson has owned his 100-year-old Victorian in the hills above Berkeley for a quarter of a century, and in that time it has transformed from an absentminded-professor type of place, cluttered mostly with books and papers, into a dense repository of stuff obscuring every available surface.

In 1994, Samson started dating a woman I’ll call Jeanne, who he met through a personal ad; they were both older, self-described “difficult” people with previous long-term relationships behind them. They quickly fell in love, but he avoided having her over to his house. According to Samson, his new partner’s high-school-age daughter told her, “He’s got a weekday wife. You’re the weekend date. I’d check that out—he’s probably got a whole family in there.” He adds, with a good-natured laugh, “The question arises fairly quickly: ‘Why aren’t we going to your house?'” The clutter was bad enough by then to pose significant navigational challenges, but people could still come inside. Samson recalls a visit his brother made around that time. “He said, ‘Wow, Greg—you’ve got a lot of problems.’ But then he added, ‘But you’ve also got some really great books here.'”

Both Samson and Jeanne were solitary people by nature, but they were attracted to each other and happily companionable; eventually, they decided to get married. They contemplated cleaning out his house so that she could move in. When I ask Samson what happened, he is slow to answer. Finally he says, “I didn’t get it together.”

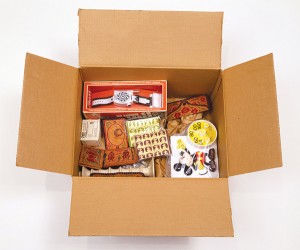

A look inside one of Andy Warhol’s time capsules. (PHOTO: COURTESY ANDY WARHOL MUSEUM)

Jeanne now lives in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, about two and a half hours from Berkeley. On Friday evenings after work, Samson drives there to spend the weekends with her. She never comes to his house; his bed is piled too high to accommodate more than one person. Her daughter doesn’t live far from Samson, so when the family spend time together in the East Bay, Jeanne stays at her daughter’s house. The couple doesn’t talk at length about Samson’s hoarding, and few outside his immediate family know about his problem.

“She’s a real tidy person, so it must have been difficult for her on some level, even though she didn’t make a big deal of it,” Samson says of telling his wife. “I imagine she took it in and decided to compartmentalize it, and to figure out what is possible to have with this guy, given this. What if I were a paraplegic or something? It’s kind of like that—it didn’t mean that was the end of the relationship. She accepted that about me, pushed it aside, and said, ‘Okay, what about the rest?’ There was hope that I would improve, but we figured something else out. We both have our way of life.”

I first meet Samson in a conference room at the major Bay Area corporation where he has worked for 12 years as a computer programmer. After most of his coworkers have gone home, we take a walk over to his cubicle. Water bottles, crumpled papers, and stacked files, folders, manuals, envelopes, and magazines crowd the work space that holds his two computer monitors and keyboard. On the floor by his chair, shopping bags, a recycling bin, bottles of juice, and a gym bag take up most of the available real estate.

“I’ve had supervisors tell me that I need to clean up,” he says. “And I get that I have a messy desk.” But as Samson sees it, the same items that are in his cubicle are in everyone else’s: papers, files, lunch, gym bag. He is unsure, then, about what bothers his coworkers. Is it the papers around the monitors? The pile of manuals behind him? The bags on the floor? Is it all of those items, or is one worse than the others? “I don’t see these things the way everyone else sees them,” he tells me.

Items found in Andy Warhol’s time capsules. (PHOTO: COURTESY ANDY WARHOL MUSEUM)

CAROL MATHEWS OF UCSF has been leading research into hoarders’ cognitive patterns. She and others have conducted functional-MRI studies that attempt to mimic the emotional decision making associated with hoarding: sorting, categorizing, thinking about discarding personal items. In these studies, people with hoarding disorder show increased brain activity in the orbitofrontal cortex, a region of the brain associated with decision making, when they’re making choices related to material things. The extra “lighting up” of the region, scientists say, is due to greater emotional engagement with belongings. And more effort than normal is needed to complete a simple organizational task. A 2012 study from Hartford Hospital has also shown that when compared with people without hoarding tendencies, hoarders experience more activity in the anterior cingulate cortex—another brain area involved in decision making—when dealing with their own possessions, and less when thinking about other people’s things. In other words: It’s tougher for hoarders to clean up their own stuff.

Mathews’ pilot studies have also evaluated the brain during simple behavioral tasks that test visual memory, categorization, information processing, and other standard functions in contexts that have nothing to do with hoarding. When asked to identify objects’ most prominent characteristics (shape and color, for example), or to group objects based on shared characteristics, people with hoarding disorder had difficulty completing the tasks. They also had trouble remembering the sequence of things (say, a group of arrows and the direction they face), and performed poorly on tests measuring attention and response time. The results show, in essence, that people with hoarding disorder have the most trouble when categorizing things.

The data are preliminary, and the studies are ongoing. But these cognitive differences may eventually represent biomarkers for the disorder. In the same way high blood-sugar levels can indicate diabetes, these differences may be something that clinicians can detect earlier, and recognize as indicators of potential hoarding behaviors. Mathews says that if treatments can be targeted at these higher-level brain functions, hoarding behaviors may improve. Samson clearly has trouble with categorization. But the way he describes his inability to comprehend the difference between his desk and his coworkers’ desks reminds me of what Randy Frost said: that hoarders literally see and treat their stuff differently. The physical world of hoarders, Frost has observed, is much more expansive than what the rest of us perceive, and is often free of the rules that we are wont to impose. Even more intriguing, Frost told me that some of the neurological hallmarks of hoarding might indicate a giftedness in the aesthetic appreciation of the physical world, rather than pure illness. One of his patients had a pile that built up in the middle of her dorm room over the course of a week; she started perceiving shapes, colors, and textures, and it became a work of art—something with aesthetic value. “She couldn’t dismantle it, because that would destroy it,” Frost said.

St. Louis-based artist and photographer Carrie M. Becker created a miniature diorama of a hoarder’s house. (PHOTO ILLUSTRATION CARRIE M. BECKER)

In a National Public Radio interview a couple of years ago, Frost talked about the reasons hoarders might collect certain items: a decades-old newspaper because it could be useful in the future; an array of bottle caps purely for their fascinating physical characteristics; a seemingly insignificant postcard because it reminded the owner of a loved one or a specific event. Frost saw universality in the way the beliefs seem to be tied to information processing. “There are some problems with attention—that is, distractibility and sometimes a hyper focus, problems with categorization, the ability to organize things,” he explained. “People who hoard tend to live their lives visually and spatially instead of categorically, like the rest of us do.” One of his patients, Irene, would put an electricity bill on top of a pile; if she needed it again, she would remember where it was in space, rather than filing it away—mentally and physically—in a “bills” category.

“We don’t know the nature of the emotional attachments that people who hoard have to objects,” Frost told me. “How do they form, and why are they so? What are the vulnerabilities that lead up to it?” Finding answers to these questions through the kind of research that he and Carol Mathews and others are doing, Frost adds, will “lead us to learn how to break those attachments, and I suspect it will drive researchers for the next decade. They are important questions for understanding how to treat someone.”

Though the nature of the emotional attachment is unclear, it is clearly powerful and often unsettling. Not long ago, I met a woman named Lindsay Smith (not her real name), who works as a peer responder at the Mental Health Association of San Francisco. For the past year, she has visited the homes of hoarders and talked in front of support groups about her own ongoing recovery from hoarding. “When I help somebody, it feels good, because it takes the focus off my own problems,” she told me. “But if we can’t help someone, it comes at an emotional cost.” She adds, “If I don’t save them, who will? It’s the same way with the objects I have in my house: I feel responsible for them.”

Going home and looking at all of her belongings, she says, is emotionally overwhelming. “Every single object has a direct tie to my heart. It’s exhausting.”

“To me, the house is a very welcoming place, because it has all my books,” Samson tells me, describing how he feels when he arrives home from work. But the emotional connection to objects can also be debilitating. In the mid-’90s, Samson was in the process of changing jobs, and was cleaning out his desk until 4 a.m., when he came across a 15-year-old software-specification document that a supervisor had recently asked him for. Samson’s heart sank—the paper was important to the company. When he found it, he says, “a lot of progress came undone for me. I’d been giving myself this pep talk where I was telling myself, ‘Nobody needs papers that are 15 years old—get rid of them.’ Instead, I thought, ‘It’s a good thing I saved this.’ It was the wrong example of what I needed.” He sighed heavily. “It resonates more deeply with me than it does with other people.”

In shows like A&E’s Hoarders, ripping off the Band-Aid by throwing things away wholesale is likely a very ineffectual way to help. (PHOTO: COURTESY A&E)

TRYING TO CHANGE HOARDERS’ behavior has proven difficult. The cognitive behavioral therapy that works well with OCD patients—stimulating unwanted thoughts in patients, then helping them learn to refrain from compulsive rituals—has not been successful with hoarders. Recent studies by Randy Frost and others have shown some success with tailored cognitive behavioral therapy. But the treatment sessions require months-long commitment, trained clinicians, and home visits. “We’re trying to come up with interventions that work but are not so costly,” Frost told me.

On those reality shows, the speed at which on-screen interventions are performed and a hoarder’s house cleared out may make sense for hour-long episodic television, but it is misleading. The programs have elevated popular awareness of hoarding, but they have also debased the behavior with sensationalized language (“it reminds me of the Chain Saw Massacre“), screechy horror-movie music, dramatic camera angles, and a decided focus on the most extreme cases.

The effectiveness of treatment can depend on whether we can identify specific characteristics. Monika Eckfield, an assistant adjunct professor in the department of physiological nursing at UCSF, has noticed two patterns of behavior in the course of her research. She calls one type of hoarder an “impulsive acquirer,” someone who actively acquires things for the thrill of it and keeps items because they reflect personal interests; she calls the other type a “worried keeper,” someone who tends to be more depressed and anxious, acquiring things passively and keeping them as a safeguard against potential future need. A worried keeper spends considerably more time trying to sort and organize belongings than an impulsive acquirer, and also feels more frustration with his or her living space. Though some participants in Eckfield’s research exhibited aspects of both kinds of hoarding, more men, she discovered, fell into the impulsive-acquirer group, and more women into the worried-keeper group.

Eckfield has also been studying later-life hoarding and the attitudinal shifts that happen with age. Hoarding disproportionately affects older adults, and she has suggested that thinking about the disorder in terms of the two different subtypes can be helpful in targeting treatment. She met Greg Samson in 2009, when he spotted a flyer and volunteered to participate in one of her studies. “What was interesting about Greg was that as he’s getting older, he had the insight that a lot of the stuff he has, he would be happy to get rid of,” Eckfield told me. Many of her study subjects also had increasingly urgent thoughts about how they were living as they aged. As Samson contemplates retirement and moving more permanently to the home where his wife resides, he has made some mental progress. “I’m starting to realize I’m never going to read all the books that I have,” he says. “If I live until I wear out all my T-shirts, I’d live to be 500. So I need to start thinking about what’s realistic.”

Randy Frost has found the people who hoard tend to live their lives visually and spatially instead of categorically, like most people. (PHOTO: COURTESY A&E)

The desire to wrap things up before death, Eckfield thinks, could be a useful motivation. “But in reality, how do you actually go about doing that?” she says. “The slow culling of stuff is where the struggle really lies.” The actual sequential planning and carry through of what goes where, which clothes need to be hung up, which ones repaired, which ones given away to Goodwill—this is where the breakdown occurs.

Eckfield thinks Samson has been unable to get rid of his things because the volume is overwhelming, not because he doesn’t want to. “There’s a real need to identify those people who would really want to get rid of these excess things if they had a trusted person to help them,” she says. There are woefully few clinicians who are trained in the slow, steady encouragement needed for a successful intervention.

Samson’s sister also has some hoarding tendencies, though her case is not as severe. So she has turned out to be the ideal person to help her brother. He explains, “A lot of people will come in and say, ‘This is just trash. Here, let me take this out to the garbage.’ And I’m like, ‘Hey! Just a second. That’s my stuff!'” His voice cracks with emotion. But he tells me that his sister said, “I’m not going to do that.” She has gently suggested that he start with one box at a time: stuff he hasn’t looked at in, say, six months. Put those boxes in a corner. The boxes would add up, but then he’d know that was was left was what he did want to look at. Deliberate decision making somehow makes it easier to think about getting rid of unnecessary items; ripping off the Band-Aid by throwing things away wholesale, the way television programs often portray a “clean out,” makes it harder. “She’s onto something, and she understands how this whole thing works, and how I feel about things,” Samson says. “It’s a process. It’s irrational maybe, but that doesn’t make it easier. It’s like having an irrational attraction, or a revulsion, to something. You can’t necessarily explain those things.”

“Recovery” is an ongoing process, one that never really ends, Lindsay Smith told me. “It can be akin to dieting. If you learn useful habits, you can apply them. But as a lot of people know, you can go off a diet and balloon up and down. For hoarders, not having our own script makes it even tougher—we’re writing it as we go along.”