Hollywood has been awash in sexual assault and harassment controversies lately. But even as the entertainment business finally reforms its culture in the wake of allegations against Cinefamily, Alamo Drafthouse, and Harvey Weinstein, many industry observers and insiders are still concerned by the amount of sexual violence that appears onscreen. According to decades’ worth of studies, exposure to sexual violence can increase men’s acceptance of violence against women and rape myths, and can decrease empathy toward alleged rape victims. In recent years, select television showrunners have pledged to rethink uses of sexual violence in scripts following controversial depictions of rape and assault on Game of Thrones.

Now, the Black List, an organization that produces an annual survey of Hollywood’s most in-demand screenplays (previous scripts include those for Slumdog Millionaire, Argo, and Spotlight) and hosts a database wherein industry professionals download and rate scripts from amateur writers, has analyzed its television and film scripts for sexual violence. On Monday, the Black List’s director of community Kate Hagen produced a summary of the results from this investigation—and they’re not good. The analysis found that, while sexual violence does not appear to be prevalent in scripts from burgeoning screenwriters, it is more common in crime genres and in scripts from male writers.

Hagen was inspired to initiate the study while reading an LA Weekly story on rape choreography for film and television. The story mentioned that the Motion Picture Association of America, which produces official film ratings, does not keep a tally on the number of films it flags for sexual violence. This left Hagen “absolutely dumbfounded,” she writes in the study summary. The Black List study she co-produced with Terry Huang, the organization’s director of product and data, sought to fill in some of these knowledge gaps.

The authors analyzed close to 45,000 television and film scripts in the organization’s database that were uploaded between 2012 and 2017. Writers and the database’s professional readers—who have screened scripts for production or management companies, agencies, or major studios—can attach topical “tags” to their scripts in the database. Looking for scripts that were tagged with “Rape & Rapists,” the only proxy for sexual violence and harassment in the database at the time, Huang found that about 2,400 scripts—approximately 5.3 percent of scripts submitted—contained these tags. (The Black List has since added “Sexual Assault” and “Sexual Harassment” to its tags list.) Feature scripts had a slightly higher percentage of “Rape & Rapists” tags, and episodic television had a slightly lower percentage.

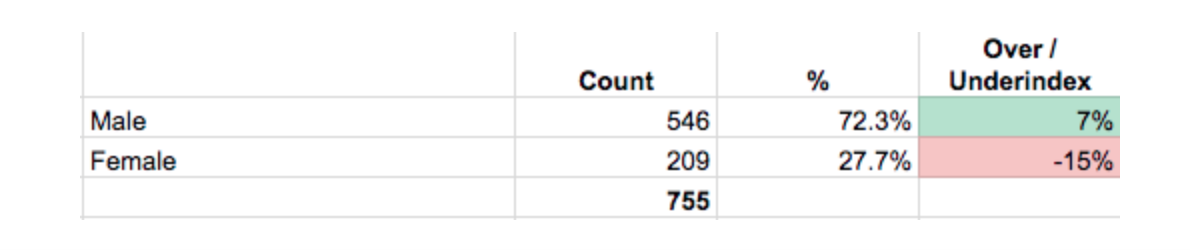

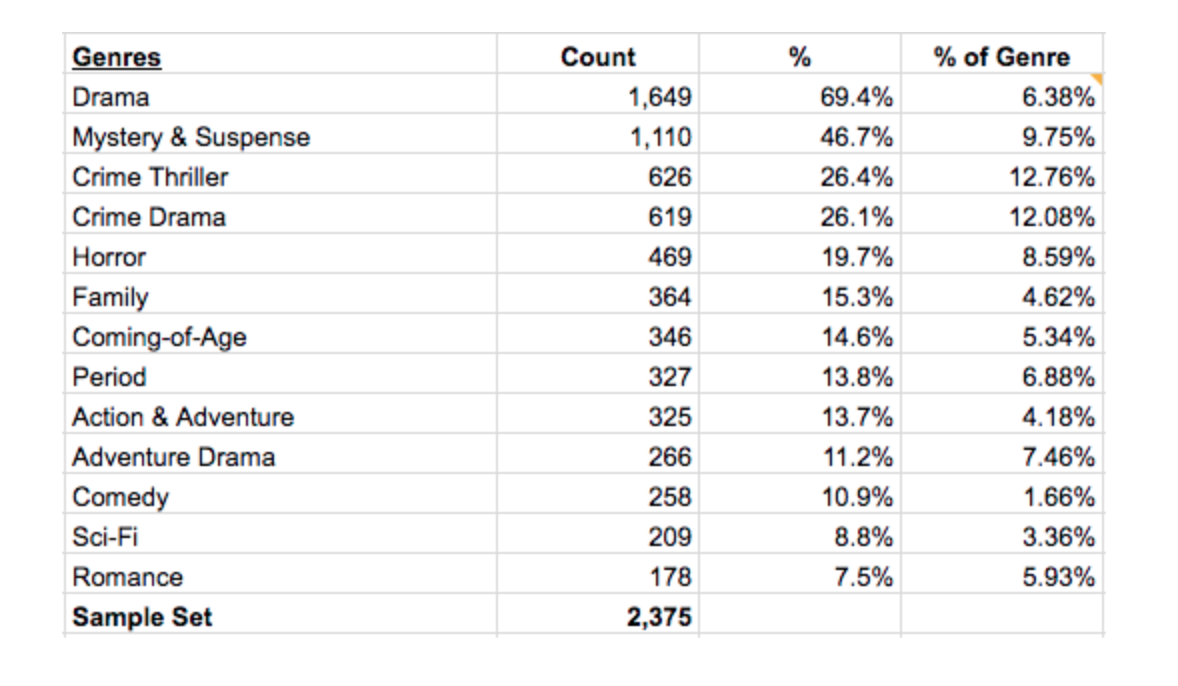

Analyzing scripts that were associated with the “Rape & Rapists” tag by the gender of the author and genre, the Black List found that the majority—72 percent—were written by men, and that crime thrillers and crime dramas had the highest incidence of the tag. Comedy, romance, and action and adventure-genre scripts had the lowest incidence of sexual violence.

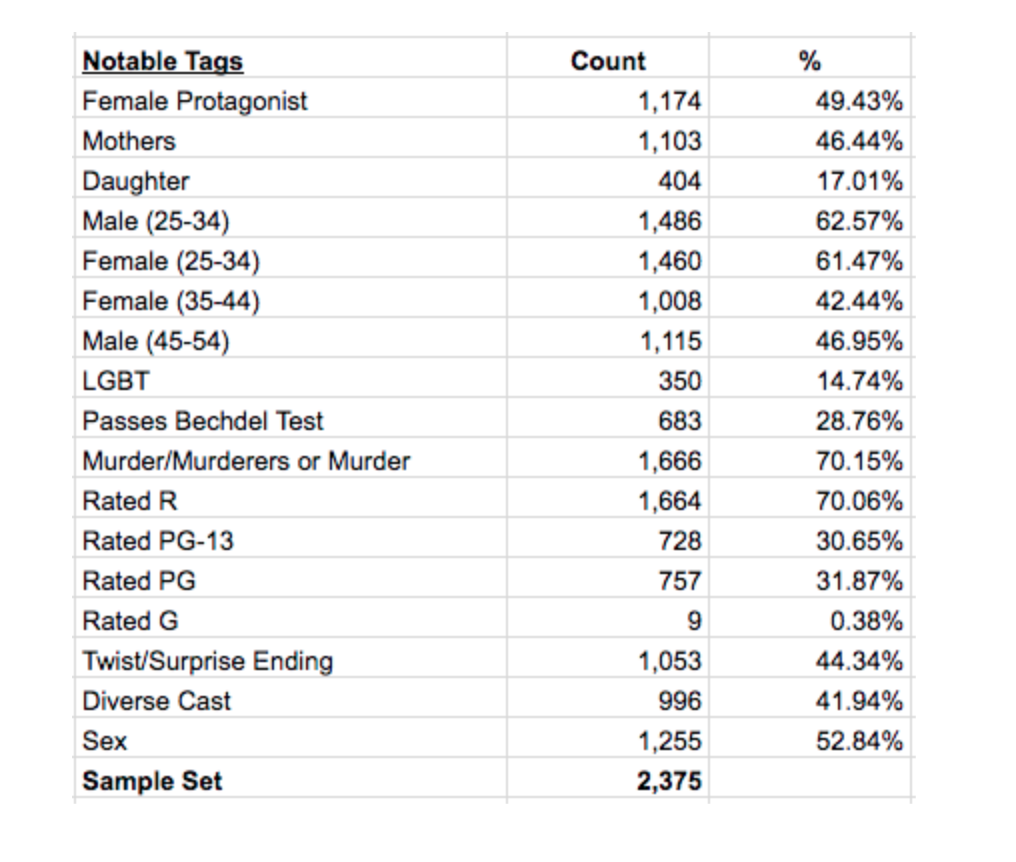

When the authors looked at tags that tended to overlap with the “Rape & Rapists” tag, they found that 70 percent of scripts with sexual violence were tagged “rated R”—the script’s predicted MPAA rating. Only 29 percent of these scripts contained the “Bechdel Test” tag—meaning that the story features at least one scene in which two or more women talk about something other than a man—though about half of them featured female protagonists.

In an email to Pacific Standard, Hagen, who has worked as a script reader, said she was not at all surprised that the majority of the “Rape & Rapists”-tagged scripts didn’t pass the Bechdel Test. “I think that speaks to how sexual violence sort of happens in a vacuum for some writers—a female character is raped, but she’s the only woman in the script, and we usually don’t get to see the aftermath of that violence. It’s extremely rare to see that trauma processed by the female character and another woman in the script in a productive way,” she writes.

In a second component to the study, the study’s authors sent out an anonymous questionnaire to its ranks of professional readers, asking for observations on sexual violence in the screenplay market. The questionnaire responses produced some eye-opening trends: many depictions of sexual violence are penned by male authors, and many scripts include “overly detailed, disturbing descriptions” of sexual violence. Readers offered some advice to writers: Scripts don’t work when sexual violence is the sole motivation for male or female characters (sorry, Sam Peckinpah) and/or do not depict the emotional aftermath to the violence.

Hagen argues in the study summary that, “when it comes to creation—the most incredible tool any of us have as writers—it is imperative that we rethink portrayals of sexual violence in any medium.” Noting that recent allegations of sexual misconduct in Hollywood have forced many victims of sexual violence and harassment to revisit painful moments in their lives, Hagen says that screenwriters do not need to compound survivors’ trauma with extravagant scenes that do not represent victims’ points of view.

And it’s not just survivors who are hurt by scenes of sexual violence: Social scientists have suggested adding a sexual violence category to MPAA classifications of “problematic content” because of such work’s effect on child psychology. Their suggestion came after studies showed that sexually violent media can change men’s feelings on violence against women and rape victims.

“With the news of the past few months continuing to snowball, I think a lot of viewers are going to be especially sensitive to inclusion of sexual violence in media, and I would hope that creators can recognize that, and make sure that their approach is a considerate one to all viewers, especially survivors,” Hagen wrote to Pacific Standard.