If everything in the world has been photographed, then everything in California has been photographed 10,000 times. Having seen the state re-produced so many times, in all its corners, it can be hard to see anything with fresh eyes. Yet I know of no better way to re-capture the surprise the first settlers must have felt at seeing the California landscape than through the photographs of Carleton Watkins.

Watkins, who came to the state in 1851 during the Gold Rush, photographed California as if it were a new planet on which he was the first person to arrive. In his own lifetime, he was best known for his mammoth-sized photographs of Yosemite and the Sequoia groves, pictures which helped persuade Abraham Lincoln to place Yosemite under federal protection in 1864. All but forgotten by the time of his death, he’s come to be considered the most important American photographer before Alfred Stieglitz. He was also one of the greatest landscape photographers anywhere, ever.

But Watkins wasn’t just a nature photographer. Much of his work was done at the behest of mining and logging corporations. Flipping through an album of his work is an education in the birth of industrial California, as well as in the destruction of its environment. Taken together, his pictures tell an epic story about the birth of Western industry, and the destruction of the frontier—one which his own life strangely mimicked. Watkins came to California following his childhood friend Collis Huntington, and Watkins’ story is really that of two lives: one made into a giant by the unfettered capitalism of the Gilded Age, the other ruined by its patterns of boom and bust.

Watkins was born in 1829 in Oneonta, New York, a small town in the northern foothills of the Catskill Mountains. His father was the town carpenter. He also owned a hotel. The hardware store in town belonged to a man named Solon Huntington. Solon had a younger brother named Collis, who was one of Watkins’ closest friends when the two were growing up. They fished and swam together in the town stream. Watkins’ father lent Collis one of the rooms of his hotel. The relationship between the two would prove to be crucial in deciding the course of Watkins’ life. And, though he couldn’t have known it at the time, Collis was about to shape the fate of the entire American West.

In 1849, a four-cent loaf of bread cost 75 cents in San Francisco, a beer went for $2, and a shovel cost $25. And for a brief time, Huntington had a monopoly on good eastern shovels. That’s how empires get born.

Watkins looked up to Collis, who was older and had seen more of the world. As a teenager, Collis Huntington worked as a peddler, traveling across the South with a pack of hardware and trinkets to sell. The experience gave him a nose for money, and sharpened his abilities as a salesman. It also instilled a lifelong restlessness, as well as a measure of daring. When Collis heard about the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, he immediately made plans to go to California. Not that he wanted to be a miner; “I never had any idea or notion of scrambling in the dirt,” he would later say. Instead, he wanted to make money selling to the miners. Collis Huntington set out from New York with a cargo of rifles, medicines, socks, and kegs of whiskey. He knew that huge profits were waiting to be made in the boom. Prices for basic necessities were skyrocketing. In 1849, a four-cent loaf of bread cost 75 cents in San Francisco, a beer went for $2, and a shovel cost $25. And for a brief time, Huntington had a monopoly on good eastern shovels. That’s how empires get born.

When Watkins came to California, he was following in Huntington’s footsteps. He arrived in San Francisco in 1851, just after a fire had burnt it down—the first of many times. Watkins then went to Sacramento, where he worked in Huntington’s store, helping deliver supplies to miners in the camps. Later, he worked as a carpenter, and as a clerk in a bookstore. He learned photography by accident. A gallery owner he knew asked him to fill in for a missing employee. All Watkins was supposed to do was to collect money and pretend to take pictures of customers; the real portraits could be re-done when they came back to collect them. But Watkins turned out to have a knack for the machine, and soon apprenticed himself to another photographer in San Jose, after which he struck out on his own.

Watkins made connections in San Francisco society. He photographed assemblies, homes, and churches. Some of his first commissions were for legal cases. In 1858, he was hired to document the site of the Guadalupe quicksilver mine to be used as evidence in a court case and later took pictures used to settle land disputes in the East Bay. The following year, he prepared an album of images of the Mariposa estate belonging to John C. Frémont, the explorer and one-time Republican candidate for president, which were used to attract European investors to Frémont’s mines. Watkins’ professional breakthrough didn’t come until 1861, though, when he undertook his first trip to Yosemite.

The photographs Watkins took in Yosemite, 30 “mammoth” views and 100 stereographs on his first trip, and many more on subsequent visits, made his reputation as an artist. They were exhibited in New York, won a prize in Paris, earned praise from Oliver Wendell Holmes and Ralph Waldo Emerson, and helped persuade Congress to set aside Yosemite for posterity. Overnight, Watkins had become an expert on the valley. Frederick Law Olmstead asked for his advice on preservation, and Josiah Whitney incorporated his images into his work on the geology of California. He even got a mountain named for himself in the park. Watkins milked the connection for all it was worth. Soon, he was selling deluxe editions of the Yosemite views, for a hefty $150 each, out of his Yo-Semite Gallery on Montgomery Street in San Francisco.

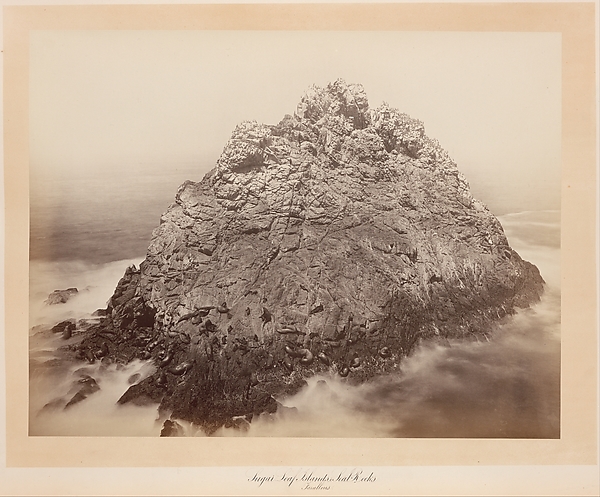

The Yosemite views brought Watkins international fame. Along with the rest of his nature photography, they are still the work he is best known for, and deservedly so, though it can be hard to understand exactly why unless you see them in person. Watkins’ work is best experienced face to face, although that doesn’t mean you can’t savored re-productions as well. Take his photograph of the Sugar Loaf Islands in the Farallons off the coast of San Francisco, one of my favorites of all his work. At any resolution, and in any medium, it’s a gorgeous image. Its composition is stark and simple. It calls to mind Timothy O’Sullivan’s great pictures of Pyramid Lake, yet Watkins’ picture is at once more austere and more alive.

The island rises out of the ocean as a pyramid of shattered rock, perfectly framed by a sepia sky. Around its base, waves dissolve into a feathery blur produced by the long exposure time. Further out, the ocean surface assumes an abstract, glassy calm. Seals perch on the islands’ base. Watkins’ camera registers them flexing on the barren rock. Higher up, a colony of murres and seagulls perches on its tallest crags, barely visible without a magnifying glass. In between, the granite is made vivid by a multiplicity of textures. Its gradient of tones—dark on the bottom from being splashed by waves, white on top from a layer of bird droppings—makes the island seem to be daily emerging out of the sea. The caption at the Metropolitan Museum says it looks like the fifth day of Creation; to me it could just as well be Mt. Ararat, when the waters started to recede after the flood.

All of this can be seen in re-production (especially with the Met’s handy zoom feature), yet none of it conveys the actual experience of confronting the work directly. Oliver Wendell Holmes said that, when viewing a good photograph, “the mind feels its way into the very depths of the picture” thanks to its “frightful amount of detail.” Seen in the original, Watkins’ work offers such a wealth of detail that one becomes lost. To look at one of the original prints for an extended period is to experience a sensation of floating simultaneously between vastly different scales of time. On one hand, Watkins’ camera sees the action of an instant; a seal arching its back, a wave breaking on the shore. On the other, it seems suspended in geologic time, witnessing the action of eons, of rocks cracking and splintering and granite mountains rising out of the sea before turning back into dust.

Seen this way, the photograph becomes a vision of sight beyond sight. Its intensity of observation seems preternatural. It transports the viewer and the viewed. Although it is rarely discussed, there is a theology to photography. It goes back to the ninth century, when the Irish Neoplatonist Scotus Eriugena said that all matter and all thought is light, and it continues in the film theorist Andre Bazin’s idea of the Holy Moment, through which film, by capturing a moment in time, also captures God in the act of creating. It might reach its highest expression though in Emerson’s notion of the transparent eyeball, which he imagined as an intelligence attuned to everything in its surroundings. That eye, which absorbs rather than reflects, is precisely what Watkins’ photographs summon. The reason why he was able to do it, though, remains an open question.

Part of it had to do with his instrument. The wet-plate collodion process Watkins used was an incredibly sensitive means of registering information about his environment. It works by using a mix of chemicals to create a photosensitive skin of silver atoms several microns thick. This skin is mounted on a glass plate and then fixed to produce the final image. You might think of the combination of plate and skin as a single solid-state memory device—one with a tremendous storage capacity. We tend to think of technological advancement as a linear process, but that isn’t always the case, especially for photography. In some ways, collodion negatives were far ahead of anything we have readily available in our digital age. It takes tens of thousands of digital images to approximate the depth of detail found in a single one of Watkins’ mammoth-size (18” x 22”) prints.

Wet-plate colloidal photography yields images of tremendous precision, but it comes with a major downside: The plates have to be prepared on the spot, and developed immediately after they are exposed. That means, wherever Watkins went, he had to have the makings of a complete laboratory and darkroom with him, as well as a stack of heavy (and fragile) glass plates. The camera itself—custom-built to his specifications, 30 inches on a side, three feet long, 75 pounds—added to the load. To accommodate this bulk, Watkins took a covered wagon with him on his expeditions, which he could also place on a railway flatcar for longer journeys. On his way to more remote locations, Watkins got more inventive. When he traveled to Yosemite, he took 2,000 pounds of equipment with him, loaded on a string of 12 mules.

Watkins was fearless about pushing himself to take photographs in barely accessible spots, from Yosemite clifftops to the peak of Mt. Shasta. By the mid-1860s he had mastered the technical side of his profession. He had also developed a great eye, and a gift for composition. Watkins knew how to balance foreground and background to create a powerful feeling of space, and how to position his camera in a way that made it seem to hover high above the ground to create an impression of cavernous depth. John Szarkowski once said that Timothy O’Sullivan’s landscapes were “as precisely and economically composed as a good masonry wall.” If Sullivan’s photographs are walls, the Watkins’ are windows punched through the picture plane and open to vast horizons.

Watkins favored straightforward compositions, which framed a single, central object or feature. Their simplicity yields unexpected riches. As Szarkowski says of Watkins’ picture of a tall strawberry tree standing alone in a field, “it is as simple as a Japanese flag, and as rich as a dictionary.” His talent appears to be sui generis. Uniquely for the 19th century, Watkins influenced painters, instead of being pulled into their aesthetic wake. While many photographers of his time tried to mimic the soft tones and diffuse light of impressionist canvases, Watkins reveled in cold precision and unorthodox perspectives. Painters of the American West like Albert Bierstadt and William Keith took notice, and used his photographs as models for their work.

Like his painter peers, Watkins usually preferred to picture landscapes without people. This has led some critics to accuse him of whitewashing California in his photographs, creating a pristine—and fictitious—nature devoid of human (and particularly native) presence. The truth is somewhat more complex. Watkins did occasionally photograph Native Americans, as in one image of a sweat house on the Mendocino Coast, a disquieting picture in which the lodge looks like a cross between caldera and an upturned tree. Watkins was also sensitive to the experiences of other newcomers to the West. He took a number of sensitive portraits of Chinese workmen, and is said to have had numerous friends in San Francisco’s Chinese community. (The exact extent of these relationships is hard to know. Only a few remaining documents by Watkins survive, giving us a very partial knowledge of his life—one of many reasons to await Tyler Green’s biography of Watkins, forthcoming from University of California Press.)

The perception of Watkins as largely a nature photographer is likewise misleading. When Watkins photographed the West, he was looking at a landscape caught in the midst of drastic change. In the years after the Gold Rush, industry and capital sought to exploit every natural resource available to it. Much of Watkins’ commercial work was done on behalf of these interests. One of his first jobs came from the owner of a mercury mine at New Almaden, south of San Jose. Later, Watkins would travel up the Mendocino coast, documenting the giant redwood-processing mills owned by the lumber baron Jerome Ford. In the Sierra foothills, he photographed the North Bloomfield gravel mines on behalf of its owners, who wanted to use Watkins’ pictures to attract overseas investors.

Watkins’ eye was equally drawn to Eden, and Eden spoiled. Some of the best pictures he ever took were of hydraulic mining, one of the most destructive forms of mining ever invented. By the 1870s, the business of gold mining had changed a great deal from the days of the original forty-niners. The days of individual prospectors were over. To be profitable, mining had to be done on a much larger scale. To get at the gold-bearing gravel locked in the soil, miners used giant, pressurized cannons to shoot jets of water at hillsides at 100 miles per hour. This procedure accelerated erosion to incredible rates. In a few years, the hydraulic mines dislodged an estimated 1.4 billion cubic yards of sediment, eight times as much as was moved in the building of the Panama Canal. The sediment caused rivers to rise and drowned farmland in thick layers of debris called slickens. So much sediment washed downstream, in fact, that the San Francisco Bay started to fill in, rising by as much as several feet in places. Mercury, used to extract gold from the eroded sediment, still leaches out of the Sierra hillsides during heavy rains. It will continue to do so for hundreds of years.

Watkins’ photographs from the Malakoff Diggings show this process in action. Whole mountainsides melting under the water cannon’s assault as if they were cakes left out in the rain. Another series of pictures, taken at the Golden Feather Mine in Butte County, demonstrate just how huge the investment of money and labor in California’s mining industry had become by the 1890s. There, Chinese Laborers diverted the whole Feather River into a gigantic flume so they could mine its riverbed for gold.

There is a hint in one of Watkins’ pictures that he missed the days when a man with a shovel could make his fortune on his own—as Watkins did. The only self-portrait we have of Watkins is of him as a prospector, panning for gold while his portable darkroom wagon sits behind him. This kind of nostalgia didn’t otherwise affect his work. He captured the emergence of the industrial West with a singularly dispassionate eye. That coolness may have had something to do with who he was working for. It may also have come from who he knew. Of all the forces working to re-make the Western landscape, none had a greater impact than the railroad. And no one had a greater role in bringing the railroad to California than his old friend Collis Huntington.

In the span of a decade, Huntington went from being a Sacramento shopkeeper to one of the builders of the Central Pacific Railroad. The Central Pacific was the western half of the first railroad to connect America from east to west. More crucially, from a business standpoint, it was the foundation for a transportation monopoly that would soon spread to dominate the entire West Coast.

Four men directed the railroad’s construction. They became known as the associates. Each of them had a different part to play in the building of the railroad. Leland Stanford was the figurehead. He had a tall frame, handsome head of hair and a booming voice, making him a plausible candidate for state-wide office. Mark Hopkins was the numbers man, keeping track of their accounts. Charles Crocker was in charge of construction, leading the work gangs in the mountains. Huntington’s role may have been the most important. He was the fixer, the influence peddler, the associates’ man in D.C.

The success of the associates had more to do with politics than with entrepreneurial skill. The rise of the associates, or the Big Four, as they were also known, involved a series of power grabs of escalating ambition. They turned local prominence in Sacramento into sway over the state-wide Republican Party, then parlayed that sway into Congressional influence, then used that influence to get their hands on wagonloads of federal pork. The way they made their fortunes had more in common with Russian oligarchs than with inventors like Thomas Edison or more conventional monopolists like John Rockefeller. Capital simply wasn’t that important to their rise. The initial stakes the partners put up amounted only to $1,500—an amount that was worth a lot in 1860 dollars, of course, but hardly a gigantic sum. What really mattered was access, and legislation.

Watkins was an artist, someone who discovered his vocation by accident but then pursued it with a restless and indefatigable enthusiasm. He knew he had the ability to see more than anyone else. He went to great lengths to see even more.

That’s why Huntington was so important. In a sense, the work of blasting tunnels in the Sierra Nevada was a sideshow, or, at least, only a means to an end. The real action involved the federal government. The railroad was a way to secure a river of public money, and then to transform that money into private property. Huntington knew who to bribe, who to spy on, when to pay, and when to lie.

Huntington was a master manipulator, equally adept at bamboozling English and German investors as he was at bending pliant senators to his will. That’s not how he saw it of course. When young men and women wrote to him asking for charity or seed capital, he would invariably write them long letters of advice about the virtues of hard work and self-reliance. He liked to make a point of being ostentatiously stingy, reprimanding one employee over a four-penny nail, and criticizing another for discarding a half-cent sheet of paper unused. “You can’t follow me through life by the quarters I have dropped” he would say, a bit rich for a man who thought nothing of spending $50,000 to buy a state legislature, or $100,000 to alter the placement of track on a map.

Huntington may have had a blind spot about himself, but he had an eye for art. On a trip to Paris in 1893, an art dealer offered him a number of canvasses for $2,000 each. Huntington liked one unsigned painting, of a girl playing a string instrument. He haggled the dealer down to $750. It turned out to be a Vermeer, the woman with a lute, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Huntington’s taste wasn’t limited to Vermeers: He also bought albums of Watkins’ photographs. He looked after Watkins in other ways as well, steering commissions from the railroad his way and making sure he could ride the rails for free. In the late 1870s, he hired Watkins to make a panoramic view of San Francisco from the roof of his Nob Hill mansion. Watkins later did the same for the other three members of the Big Four, photographing each of their mansions in turn.

It must have been odd work for Watkins to undertake, for as Huntington’s fortune rose, his own fell. Watkins never had a good head for business. His brief fame after the publication of the first Yosemite albums brought him a burst of income, but he spent most of that money on ambitious expeditions in pursuit of ever-more-elusive views. He didn’t do many portraits, the mainstay of most studios, preferring to live off of his landscape work. He wasn’t careful with his copyrights. East Coast photographers pirated many of his prints. In 1875, Watkins went bankrupt and lost his gallery and control over his negatives. A rival San Francisco photographer began publishing his views as his own.

After his bankruptcy, Watkins had to re-build his inventory from scratch, re-shooting the pictures that had made his name. In subsequent years, he kept getting work, but it was never enough to cover his expenses. In one of the few surviving letters we have from him, he writes to his wife Frances that “if this business don’t give us a living we will go squat on some government land and raise spuds.” By the 1890s things had grown truly desperate. Watkins’ eyesight was failing, along with his health. For 18 months, the family lived out of a railroad car. Huntington saved them by giving Watkins the deed to a ranch owned by the Southern Pacific in Yolo County. His son, named Collis, after his friend and benefactor, helped him process negatives, keeping the family afloat.

The final blow came a few years later. Watkins had tried for years to find a home for his archive of work—and with it, some recognition of his stature as an artist. In 1906, the curator of the Stanford Museum agreed to buy all his work and safeguard it permanently in Palo Alto. But just as Watkins was about to hand off his archive, the earthquake struck. Watkins lost his studio and all his negatives. The loss broke him utterly. He spent his last years in the Napa Hospital for the Insane. He died there in 1916, and was buried in an unmarked grave.

Seen from the vantage point of this blank grave, and the ruin that came before it, Watkins’ life feels like something out of Dreiser. Seen from its beginning—the summers in Oneonta, the trip West with his best friend—it reads like a story by Mark Twain. Neither version offers the full truth. Watkins was an artist, someone who discovered his vocation by accident but then pursued it with a restless and indefatigable enthusiasm. He knew he had the ability to see more than anyone else. He went to great lengths to see even more. Even to the tops of mountains.

In 1870, Watkins took his camera, tripods, chemicals, and plates to the summit of Mt. Shasta. As always, he had to develop his pictures on the spot. The climb was dangerous and the terrain hazardous. The only place to pitch a tent for his darkroom was on a small frozen pond of blue ice. Watkins knew that the glow off the ice was enough to ruin a good plate. That’s where I’d like to leave him—not yet a pauper or a giant, just a craftsman, spreading a blanket on the ground to keep out the light.