When Kenneth Williams was a child, his father beat him regularly with a belt. One time, he threw Williams against a wall, injuring his brain. Besides the trauma stemming from this abuse, Williams was also forced to witness similar violence against his mother and siblings. In school, Williams was diagnosed with severe learning disabilities, perhaps related to the brain injury, or from exposure to toxic chemicals and drugs. Although three experts examined Williams and determined that he met the criteria for the definition of intellectual disability, which should have protected him, the Supreme Court declined to stop his execution. He died on April 27th.

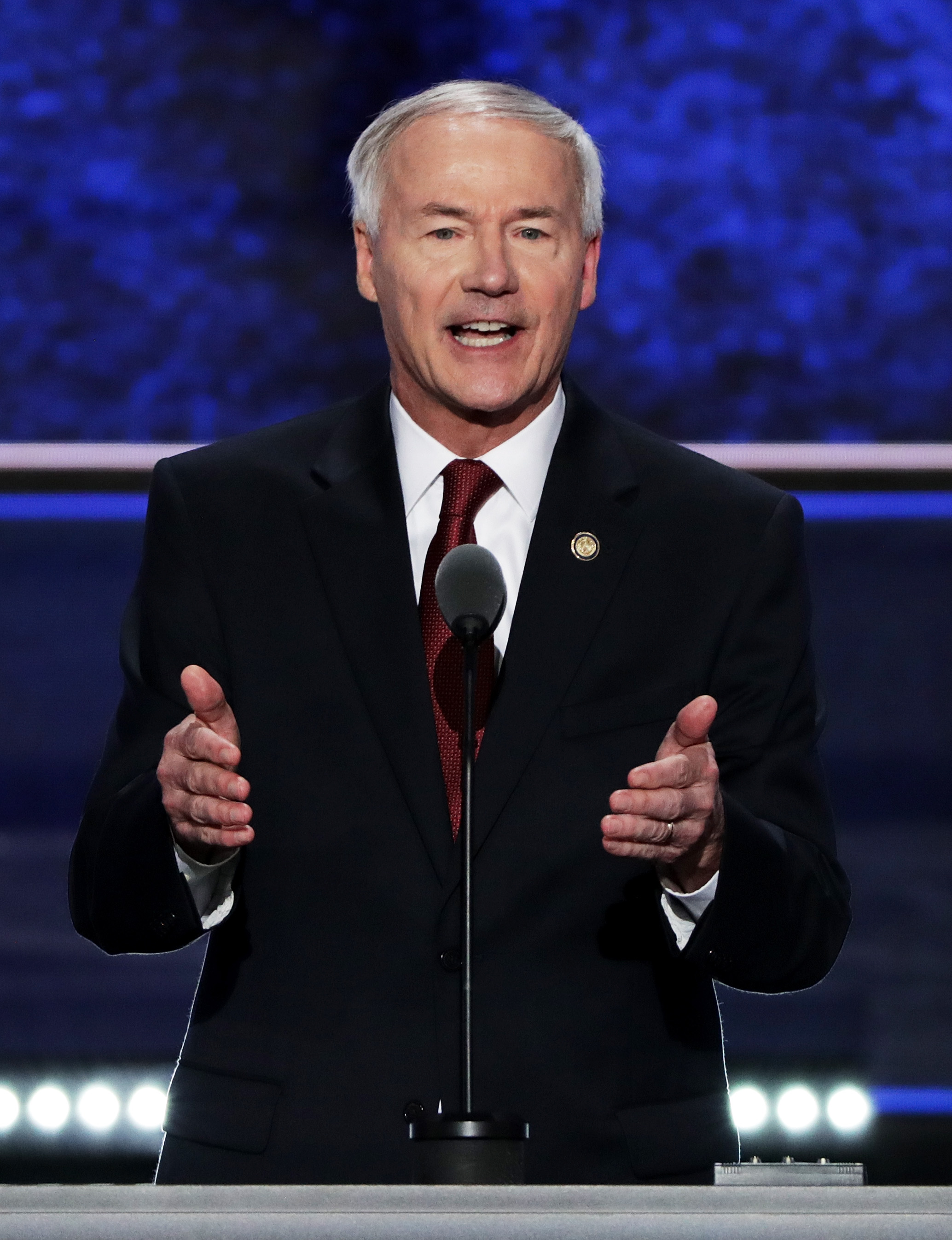

Williams was the fourth person executed by the state of Arkansas this April. Arkansas Governor Asa Hutchinson had signed the warrants of execution as he rushed to use up the state’s supply of lethal-injection drugs before they expired. All four of the executed men were disabled. Jack Jones was wheeled into the execution chamber because one of his legs had been amputated owing to diabetes. He also had bipolar disorder. Marcel Williams had been exposed to extreme trauma as a child, including repeated rape, and had intense post-traumatic stress disorder. Ledell Lee had fetal alcohol syndrome resulting in intellectual disability. Lee might also have been innocent.

After fervent efforts by lawyers and activists failed to stop the executions, I began to think about the fact that four of the four executed men were disabled. I started to talk to death penalty experts around the country, seeking an answer to what I thought was a simple question: What percentage of people sentenced to die in the United States are disabled? Our best guess: all of them.

As a concept, disability includes diverse types of conditions and needs, so maybe it’s not a surprise that there’s no comprehensive database to track all possible disabilities among America’s prisoners. We know, though, that a high percentage of prisoners are disabled, especially on death row. A recent American Civil Liberties Union report on the abuse of physically disabled prisoners estimates that 30 percent of all state and federal prisoners, and 40 percent of all local prisoners, have at least one disability.

Far from being an instrument of justice, the death penalty reflects and intensifies broader injustices resident in American society.

The numbers of disabled prisoners on death row is much higher. A study from the Fair Punishment Project of the 16 counties most likely to execute someone found that 40 percent of the prisoners on death row had “intellectual disability, brain damage, or severe mental illness.” Those are just a small slice of possible types of disabilities. Another FPP report determined that, in Oregon, “two-thirds of death row inmates possess signs of serious mental illness or intellectual impairment, endured devastatingly severe childhood trauma, or were not old enough to legally purchase alcohol at the time the offense occurred.” A 2014 study in the Hastings Law Journal examining the social histories of the last 100 Americans to be executed found “that the overwhelming majority of executed offenders suffered from intellectual impairments, were barely into adulthood, wrestled with severe mental illness, or endured profound childhood trauma. Most executed offenders fell into two or three of these core mitigation areas, all which are characterized by significant intellectual and psychological deficits.”

Denny LeBoeuf is the director of the ACLU’s John Adams Project, which provides direct representation in the capital trials for detainees at Guantánamo Bay. Before that, she ran the ACLU’s Capital Punishment Project for years. Over the phone, I ticked off all the disabilities present in the four executed men in Arkansas—fetal alcohol syndrome, bipolar disorder, diabetes, learning disabilities, and many incidents of severe trauma. “Nothing about what you just said surprises me,” LeBoeuf said. “We almost always find two of the big three: terrible trauma, cognitive disorder, and severe mental illness. To find someone who doesn’t have one of the three, well, I’ll tell you when that happens. I took my first capital case in the late ’80s, and I’ve not seen a single case without significant trauma or other mental-health mitigation.” Moreover, according to LeBoeuf, death row is “designed to break you,” and inmates tend to get little in the way of medical care, whether for physical or mental ailments. Diabetes and other conditions related to diet and exercise are common, LeBoeuf told me, though she doesn’t think anyone is tracking that kind of data on a national level.

Both LeBoeuf and Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center and a lawyer in capital cases, admitted that there’s a potential tension between the disability-rights community and the anti-death-penalty community. Defense lawyers want to portray disability as a mitigating factor, so their arguments often posit their clients’ lack of ability to understand their actions or control themselves. These lawyers know that most disabled people aren’t violent, but when it comes to keeping one’s client alive, all arguments have to be on the table. Disability-rights activists, meanwhile, are working to normalize disability.

Prosecutors are no less likely to apply stereotypes about disability to serve their purposes. As I reported while covering Moore v. Texas, prosecutors like to assert that any evidence of function means there’s no relevant disability. As Dunham puts it: “The prosecutors, over and over again, in imploring juries to return death verdicts, use pernicious stereotypes about disabilities. They say, ‘Well this person can’t be intellectually disabled because they can can drive a car, or they got a GED, or they fathered children.'” Dunham would like to see the alliance between the disability-rights movement and the anti-death-penalty movement emphasize treating people with dignity, no matter their level of functioning—in other words, recognizing the many competencies of disabled people without setting them up to be executed. Defense lawyers, Dunham says, emphasize “impairment and the inability to overcome. To the extent that the inability to overcome is associated with a disorder, it paints those who haven’t overcome in a negative light.”

(Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images)

There’s reason for hope. The state-by-state shift away from executing people with intellectual disabilities, Dunham tells me, happened thanks to collaborations between anti-death-penalty activists and disability-rights organizations. That effort culminated in 2002 with the Atkins v. Virginia Supreme Court ruling that people who met certain definitions for intellectual disability couldn’t be executed. Over the past few years, Dunham has begun to see similar collaborations focused on shifting norms related to mental illness and the death penalty.

LeBoeuf, moreover, is eager to try an approach that a few capital litigators have pursued. “I believe,” she says, “that we should increase litigation about reasonable modifications pre-trial and during trial. I don’t think that, for example, somebody who had a learning disability and severe trauma was capable of sitting through a full day’s testimony in court and processing it. Court is very stressful, the stress goes up when the consequences go up, and there are no more significant consequences than ‘the words these people are saying are going to determine whether I live or die.'”

Under the Americans With Disabilities Act, she says, a disabled person has a right to accommodations and modifications during any court process, a right that death-penalty lawyers have not consistently demanded be recognized. Court paperwork should be modified to be accessible to those who do not read. Verbal statements should be provided in writing or on a monitor for those with aural processing challenges. LeBoeuf wants to implement shorter trial days and more breaks for people with ADHD or brain injuries (just for example). “We should have more breaks,” she says, because we need to make sure defendants understand what’s happening in court. “If [the defendant] can’t answer a few simple questions, i.e. if he’s having mini-seizures, that’s kind of bad for his trial. He is supposed to be able to cooperate and consult with counsel. It’s also very mitigating!”

LeBoeuf’s voice grows excited as she contemplates this new legal angle, but then she catches herself and returns to my opening question—my reaction to the deaths in Arkansas. “Are we basically executing disabled people? Yes. Yes we are. We are executing poor people. We are executing people with bad lawyers.”

Far from being an instrument of justice, the death penalty reflects and intensifies broader injustices resident in American society. It’s time to add disability—all disabilities—to the many ways in which the death penalty discriminates. We can no longer help the four men in Arkansas, but it’s not too late to save the next life.