Medicare is wasting hundreds of millions of dollars a year by failing to rein in doctors who routinely give patients pricey name-brand drugs when cheaper generic alternatives are available.

ProPublica analyzed the prescribing habits of 1.6 million practitioners nationwide and found that a tiny fraction of them are having an outsized impact on spending in Medicare’s massive drug program.

Just 913 internists, family medicine, and general practice physicians cost taxpayers an extra $300 million in 2011 alone by disproportionately choosing name-brand drugs. These doctors each wrote at least 5,000 prescriptions that year, including refills, and ranked among the program’s most prolific prescribers.

Many of these physicians also have accepted thousands of dollars in promotional or consulting fees from drug companies, records show.

While lawmakers bitterly disagree about the Affordable Care Act, Medicare’s drug program has been held up as a success for government health care. It has come in below cost estimates while providing access to needed medicines for 36 million seniors and the disabled.

But this seeming fiscal success has hidden billions of dollars lost to unnecessarily expensive prescribing over the program’s eight-year history.

The waste is exacerbated by a well-meaning benefit written into the drug program, known as Part D: low-income patients pay less than $7 per prescription regardless of a medication’s cost. The unintended consequence is that doctors can dole out name brands with little fear of pushback from patients about price.

Taxpayers spent $62 billion last year on Part D—more than a third of it on this low-income subsidy.

Dr. Hew Wah Quon is one of Medicare’s top prescribers. From a worn office in Los Angeles’ bustling Chinatown, he churned out $27 million worth of prescriptions from 2009 to 2011, data show.

All of Quon’s patients in 2011 qualified for the low-income subsidy, sometimes called “Extra Help.” He mostly prescribed name brands, such as AstraZeneca’s Crestor, for high cholesterol. Crestor costs more than $6 a pill; the leading generic costs as little as 20 cents.

If Quon had prescribed the way other internists do in California, choosing drugs so that his average cost was similar to theirs, he alone could have saved Medicare $5 million in 2011, ProPublica’s analysis shows.

“Boy, this doctor is a walking economic disaster,” said Dr. Jerry Avorn, a Harvard medical professor who has written about the risks and benefits of prescription drugs.

When first contacted by ProPublica last year, Quon defended some of his choices but abruptly ended the interview and has since declined to comment. Others who prescribe similarly said they believe name-brand drugs work better.

Health programs run by the U.S. military and the Department of Veterans Affairs control costs by strictly limiting the name-brand drugs doctors can prescribe. Some of the nation’s leading private health insurance plans do as well.

But Medicare, which pays for one in every four prescriptions nationwide, hasn’t asked Congress for the authority to put similar checks in place.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the federal agency that administers those programs, declined to make an official available for an interview and would not answer specific questions.

“By law, Medicare must cover items and services that are reasonable and necessary,” a CMS spokesperson said in an email. “Within those rules, doctors and their patients are free to make medical treatment decisions that are best for the patient.”

In the past, agency officials have said that while Part D is a government program, private insurers are responsible for running it. They normally decide how to manage their drug plans but cannot increase prices for the poor.

ProPublica’s analysis is part of a broader look at Part D oversight. An article in May found that Medicare has failed to take basic steps to investigate doctors who prescribe large quantities of dangerous, addictive, or inappropriate medications.

Some, including the investigative arm of the Department of Health and Human Services, say CMS also needs to do more to stop waste—by investigating doctors who prescribe very differently than their peers. Others say it should establish penalties and bonuses to encourage more cost-effective habits.

“At some point, I think we have to hold prescribers accountable for their prescribing,” said Dr. Nancy Morden, an associate professor at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, which has studied Part D. “I just don’t see how that’s different from holding them accountable for the quality of care in the exam room or in the operating room.”

Numerous studies show that generics, which must meet rigid Food and Drug Administration standards, work as well as name brands for most patients. Although some medications do not have exact generic versions, there usually is a similar one in the same category.

Many of the 900-plus primary care doctors who favored name brands shared another trait: financial ties to the companies whose pills they prescribe.

Since 2009, 48 percent of them have received at least $1,000 for speaking, consulting, and other promotional purposes, according to data ProPublica compiled from company websites. Eleven have accepted $100,000 or more, the data show. Quon has received more than $7,000 in speaking fees and meals.

Among a random sample of doctors who prescribed generics more frequently, only 15 percent accepted drug company money, and the amounts generally were less.

Dr. Jeffrey Grove, a Florida physician who chooses generics 90 percent of the time for his Medicare patients, said it’s irresponsible not to consider cost.

“I don’t care that the government pays for it,” said Grove, president of the American College of Osteopathic Family Physicians. Grove was at the 2003 ceremony when President George W. Bush signed Part D into law.

“How many people could we insure that are uninsured right now if those physicians were practicing responsibly as well?”

KING OF THE NAME BRANDS

Quon’s office, right outside downtown Los Angeles, is wedged between a bank and a budget hotel. His name is half-peeled off the front window. On the waiting room walls, smudges mark where legions of patients leaned their heads.

Yet in 2011, nearly 80,000 prescriptions flowed through this unassuming space and his other office in Monterey Park, a largely Asian city nearby.

Quon, 62, was the nation’s top prescriber that year for a dozen brand-name drugs and second-highest for another 13.

High on his list was Crestor, the most potent of a class of cholesterol-lowering drugs known as statins. Quon prescribed it 5,250 times—more than twice as many as any other doctor in Medicare. About 70 percent of his 948 Medicare patients filled a prescription for it.

Doctors typically find that generics such as simvastatin, the most-prescribed drug in Part D, work well to treat the risks from artery-clogging cholesterol. Crestor is usually reserved for stubborn cases because it costs 30 times as much.

Quon also liked Lovaza, purified and concentrated fish oil. It is marketed by GlaxoSmithKline to help reduce very high triglycerides, a fat in the blood linked to heart disease. At more than $90 per prescription in 2011, Lovaza’s price dwarfed that of over-the-counter fish oil supplements sold for a few dollars per bottle. Quon prescribed it 4,700 times, tops in the country.

Dr. Steven Nissen, chairman of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, said that while high triglycerides are a risk factor for heart attack and stroke, there is no scientific evidence that Lovaza lowers the odds of either event. Even GlaxoSmithKline says on the drug’s website that, “It is not known if Lovaza prevents you from having a heart attack or stroke.”

Nissen said it is “absolutely inconceivable” to treat so many patients “with a drug approved only to treat a relatively rare disorder.”

Another Quon favorite is Forest Laboratories’ Bystolic, which treats high blood pressure. He prescribed it 2,225 times, second-highest among Medicare doctors. Several drugs in the class, known as beta blockers, are generics and cost less than $10 per month. Each of his Bystolic orders cost $58.

The FDA has said Bystolic had no proven advantage over generic beta blockers. In 2008, it warned Forest Labs that its ads overstated the drug’s benefits.

Quon’s prescriptions for Crestor, Lovaza, and Bystolic alone cost Medicare $1.3 million in 2011. Overall, his patients received name brands 75 percent of the time, compared to 23 percent for all California internal medicine specialists, including Quon. The average cost of Quon’s prescriptions was $129; the group’s was $65.

Medicare data show a consistent pattern for Quon since at least 2007.

“He is a big brand user. That’s his style,” said David Wong, whose C.T. Pharmacy is down the block. “He’s famous.”

The prescribing habits of Quon and other primary care doctors with similar devotion to name brands collectively cost Medicare more than $1 billion in 2011. Nearly a third of that could have been saved if their prescribing had the same average cost as their peers.

Other specialties showed comparable patterns, but ProPublica’s analysis focused on primary care doctors because they treat a variety of illnesses and prescribe a range of medications that have generic alternatives.

In June, the HHS inspector general issued a report on potential waste and abuse in Part D. Among a group of “very extreme outliers,” the report cited one doctor with an “unusually large number” of Lovaza prescriptions whose costs in 2009 were 151 times more than average.

The inspector general did not name the doctor, but by matching statistics in the report to Medicare data, ProPublica was able to identify the doctor as Quon. No other physician met the criteria.

FOR THE POOR, PRICIEST PILLS

Part D was created amid a partisan fight over who should run the program—the government or private industry. But it was accepted that no matter who was in charge, poor Medicare enrollees would need extra help paying their drug bills.

Today, this special subsidy has ballooned into the program’s biggest cost, hitting $22.8 billion in 2012, according to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), a group that reports to Congress on Medicare. That’s up 35 percent since 2007.

The growth has been fueled in part by the meager co-pays set by Congress.

For the more than 11 million who get the subsidy, generics cost no more than $2.65. Even the most expensive drugs cost the patients $6.60 or less.

Medicare reimburses drug plans for the difference between these amounts and what other enrollees pay.

With little incentive to be cost conscious, these patients and their doctors often use name brands when generics are readily available, studies show.

For others in Part D, typical co-pays for brand-name drugs—$40 to $85—deliver a strong push toward generics, which generally cost less than $5.

A MedPAC analysis found that if low-income patients were prescribed generic drugs in the same proportion as other Medicare enrollees, the program could save $1.3 billion a year in just seven drug categories. A separate study this year by the Bipartisan Policy Center, a Washington think tank, says savings could be greater across the program, perhaps as high as $44 billion in a decade.

“I really think that you need both the carrot of lower cost for the generic side as well as the potential stick of higher costs on the brand side,” Bruce Stuart, then a MedPAC member, said at a meeting last year. Stuart heads the Peter Lamy Center on Drug Therapy and Aging at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy.

Experts say that if patients had to pay higher co-pays for name brands, they would likely ask for something cheaper.

There’s no sign that the rules for Part D’s low-income subsidy will change anytime soon, however. Last year, MedPAC urged Congress to modify the co-pays to spur greater use of generics. President Obama proposed raising brand co-pays and reducing generic ones in his 2014 budget, but Congress hasn’t acted on it—and likely won’t.

Former CMS administrator Mark McClellan said encouraging greater use of generics makes sense. But faced with angering either the powerful pharmaceutical lobby or advocates for the poor, he said, lawmakers may see no political benefit in pushing a change.

The drug industry’s leading trade group, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, opposes higher brand co-pays for the poor. And the group has a history of batting away proposals that might cut into the billions of dollars of profits drug makers earn from high-margin products in Part D.

When Congress debated Part D in 2003, the group lobbied to kill a Democratic proposal to let the government negotiate volume discounts on drugs. In 2010, it helped squelch efforts to allow imports of cheaper drugs from abroad as part of the Affordable Care Act’s expansion of Part D.

Matt Bennett, a senior vice president with the group, called Part D a “success for both beneficiaries and taxpayers.” In a statement, he said, “Improved access to medicines in Part D not only leads to better health outcomes for patients, but it also lowers other Medicare spending.”

It’s illegal to pay to doctors to prescribe, but the money drug makers give doctors to speak or consult on their behalf appears to be a good investment. In June, ProPublica reported that 17 of the top 20 prescribers of Bystolic, including Quon, received speaking fees in 2012 from the manufacturer, Forest Laboratories.

The pattern extends to Part D’s top name-brand prescribers. Two doctors, in Kentucky and New Jersey, have each received more than $225,000 in promotional payments from drug makers since 2009. A large chunk came from AstraZeneca, maker of Crestor, the doctors’ most-prescribed drug.

AstraZeneca spokeswoman Michele Meixell said the company doesn’t choose its speakers based on prescribing but on “expertise in a therapeutic area, experience and qualifications.”

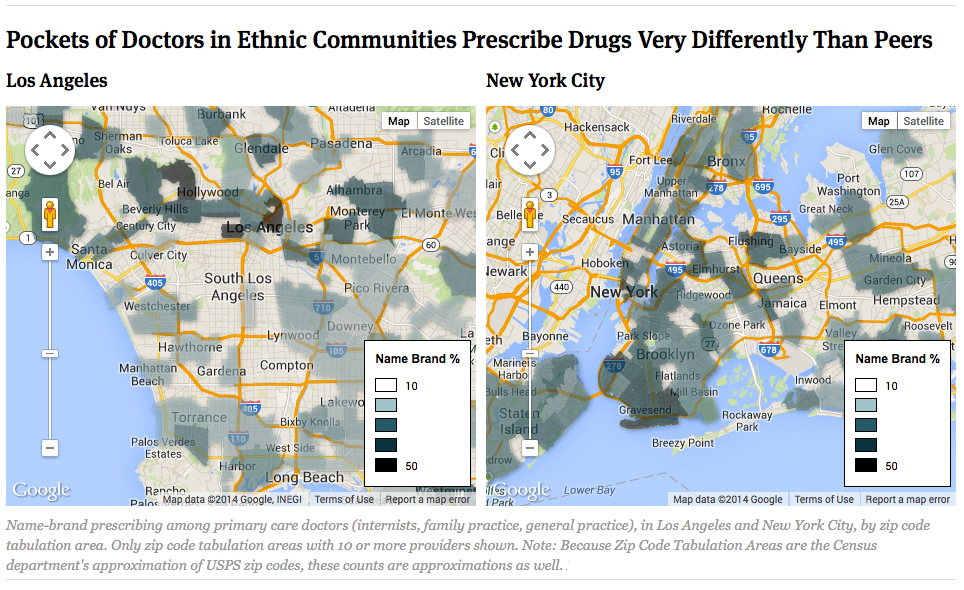

PART D’S ETHNIC HOT SPOTS

Along one mile-and-a-half stretch of Los Angeles’ Koreatown, seven primary care doctors have some of the highest rates of name-brand prescribing in the country. Nearly 3,000 miles away in Brooklyn, New York, a single building in a Russian community houses six such doctors.

By mapping doctors who favor name brands, ProPublica found unexpected clusters in ethnic neighborhoods in and around the biggest cities. The average cost of a Part D prescription in these enclaves can be more than 50 percent higher than that of surrounding areas, the analysis showed.

Researchers have previously noted regional differences in the way doctors prescribe drugs. But ProPublica’s analysis aimed to unravel which individual doctors drive name-brand prescribing and what, if anything, they had in common.

Many worked solo or in small groups. Often they received their medical training outside the United States, records show.

Doctors’ drug choices can be influenced by many things—their peers, patient requests, a chat with a sales rep, or studies in medical journals. In recent years, concern about undue influence has prompted many academic medical centers and large group practices to ban sales reps and to refuse free samples.

But many physicians in ethnic communities continue to embrace these relationships. When reporters visited offices in such neighborhoods of New York City and Southern California, drug reps crowded the reception counters as they unloaded rolling suitcases full of samples or waited to speak to the doctors.

Chinatown is one of the most densely populated parts of Manhattan. Outdoor fish markets crowd next to storefronts selling counterfeit handbags and pirated DVDs. Every block seems to have at least one pharmacy, and hundreds of medical offices are stacked above and around them. More than 90 percent of Part D prescriptions written in 2011 by these doctors were for the poor, Medicare data show.

The neighborhood is home to 20 high-prescribing primary care doctors who disproportionately favor name brands.

One of them, internist George Liu, is a founder and longtime leader of a prominent Chinese-American physicians’ association. In 2011, Liu wrote more than 9,000 prescriptions—47 percent for name brands. By comparison, all internists in New York used name brands, on average, only 27 percent of the time.

Liu, who specializes in diabetes, said he does his own research on drugs and doesn’t depend on sales reps. A “new drug has a reason why it’s on the market,” he said.

Liu has given lectures for the makers of his favored drugs, he said. Three of his top 10 drugs are made by Eli Lilly, which has paid him $123,000 since 2010. One Lilly osteoporosis treatment, Forteo, cost Medicare $1,140 for a month’s supply.

Liu said scrutinizing how doctors use name brands is an “incorrect way of looking at medical care.” He and his peers are saving Medicare money, Liu said, by staying open long hours and keeping patients from costly emergency room visits.

In an office nearby, Dr. Henry Chen praised Part D for making it easy for poor patients to get name brands. He said it’s wrong that state Medicaid programs for the poor and some private insurers force doctors to get prior approval before prescribing them.

Chen wrote more than 50,000 prescriptions in 2011, placing him among the top 100 prescribers nationally in Part D. Forty-five percent of his prescriptions were for name brands. He said picking a drug is like choosing how to get from New York to Washington.

“You could drive a Mercedes-Benz. You could drive a Rolls-Royce. Then you can drive a horse,” he said. All three would get you there, he said, “but the speed and the quality is different.”

Chen, who also has an office in Brooklyn, was paid $11,400 to deliver promotional talks for Eli Lilly and Merck last year. In 2011, he received more than $2,500 in meals from Lilly alone. Two of the drugs in his top 10 are made by Lilly and another by Merck.

Dartmouth researcher Morden said doctors in these areas are shifting the excess costs to others. “The other person one neighborhood over who’s getting a generic product is subsidizing the brand products for that whole neighborhood,” she said.

Not everyone in Chinatown defends such prescribing.

Dr. Perry Pong, chief medical officer of a local health center, was dismayed to hear that his colleagues stood out for pricey drug choices: “That’s bad. I’m ashamed of that.”

Pong said his center tells doctors to use generics first. But Medicare’s figures show some haven’t done so, and Pong said he couldn’t explain it.

‘THE LIGHT BULB GOES OFF’

Pharmacist Mark Greg mimics the time-tested tactics of drug company sales reps. Like them, he studies doctors’ prescribing records, arms himself with medical studies and even provides lunch.

The difference: Greg is pushing generics.

He works for Advocate Physician Partners, part of a Chicago-area hospital chain that gives doctors bonuses for meeting performance measures that include generic use.

Greg, the group’s manager of clinical programs, asks doctors to see things from the patient’s point of view.

“Would you want to pay $10 a day for the same benefit as you would get for paying 10 cents a day?” he said. “In many cases the light bulb goes off.”

At one Advocate clinic in Chicago, 11 primary care physicians prescribed at least 80 percent generics in 2011. One of them, Dr. Tony Hampton, had an average prescription cost in 2011 of $41—versus $89 among the 900-plus high name-brand prescribers in ProPublica’s analysis.

Hampton wrote more than 14,800 prescriptions in Part D, 13 percent of them for name brands. He said he gets very little resistance: “It’s just a few patients who need that little extra push.”

Across the country, private practices and government agencies have tackled the high cost of prescribing and determined that they can trim spending without sacrificing patient care. Some tightly control the drugs doctors can prescribe; others ramp up the co-pays on costly drugs.

Some with the lowest name-brand use have close ties to insurance companies, such as Kaiser Permanente and Southwest Medical Associates in Las Vegas, which is owned by UnitedHealth Group.

At both Southwest and Advocate, patients taking generics have met or exceeded national success rates for lowering cholesterol and controlling diabetes.

“You can be cost-effective and have high quality,” said Dr. Linda Johnson, medical director for primary care at Southwest. Johnson and others said only a small percentage of patients react negatively to slight fluctuations in their medications and require a name-brand drug.

Mitra Behroozi, executive director of the 1199SEIU Benefit and Pension Funds in New York, said her union’s health plan offers its 400,000 enrollees at least one option in each drug class, usually a generic, that is free. Members who want a name brand must spring for the difference, which can top $100 in some cases.

“We don’t pay for the latest, greatest if it’s not more efficacious,” she said.

The VA is likewise strict, often requiring prior approval for brands when generics are available. More than 80 percent of the 140 million prescriptions written annually by its doctors are for generics, said Mike Valentino, the agency’s pharmacy chief.

“We take out of the equation the marketing and advertising that drives so much of the prescription drug utilization in this country,” Valentino said.

The push has had a massive payoff.

Researchers have compared the VA’s prescribing to Part D’s. In a study that examined diabetes, cholesterol, and blood pressure-lowering drugs, they found name-brand use under Part D in 2008 was two to three times higher than in the VA.

Medicare could have saved $1.4 billion if prescription choices mirrored those in the VA, according to the study, published in June by the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Lead author Dr. Walid Gellad, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh, said that Medicare needs to follow the VA or create a system that tracks doctors and rewards or punishes them for their choices.

“There’s this big narrative that Part D has been this huge success because it’s come in under budget,” Gellad said. “My personal opinion is that we could have done a lot better.”

This post originally appeared on ProPublica, a Pacific Standard partner site.