The marathon-as-spectacle is, more than any other sporting event, built on the responsibility and rationality and general non-wickedness of other human beings. You’re at this long, winding, sweeping thing—event really is the best way to put it. It’s a stadium 26.2 miles long. And you’re allowed to be up close to the competitors—cheering them on, handing them water, sneaking onto the course and claiming you’ve won—at any point.

Marathon Day was Boston’s day to not be Boston. That is, the day that all the stereotypes of the city—loud, belligerent, belligerently drunk fans yelling loud, belligerently offensive things—get flipped around. It’s a Boston holiday—the Red Sox play at 11 a.m., then you go sit on a rooftop, drink what you want to drink, and watch the slightly more ambitious go past as part of their long run—and it’s only a Boston holiday. And it’s that way, at least in large part, because of the marathon and how it’s a race that’s everywhere and open to everyone. It’s naïve in the best and most basic way: people are good; we don’t have to worry about trusting them. As Boston University graduate Erik Malinowski wrote over at BuzzFeed:

If you’ve never run in, or even merely attended, the Boston Marathon, there are some unequivocal facts you should know. First, it’s an extremely open event, in the sense that the only thing separating you—well, you and a couple hundred thousand of your fellow spectators—from the planet’s most elite runners is usually nothing. Sometimes, it’s one of those easily moveable steel police barricades, sometimes it’s a piece of race tape, sometimes it’s the stern hand of a volunteer. But sometimes it’s nothing, and people are always running from one side of the course to the other. You have to time it like you’re running across the street in Rome. Runners come by out of nowhere and you don’t want to be the guy who accidentally tripped the lead runner when he was a mile or two from history.

And now that’s gone. Maybe not next year, maybe the openness of it all will return in 364 days, but right now, a day after those bombs went off and this eight-year-old died and people lost their limbs, it has to be different. Marathon violence now exists in this country.

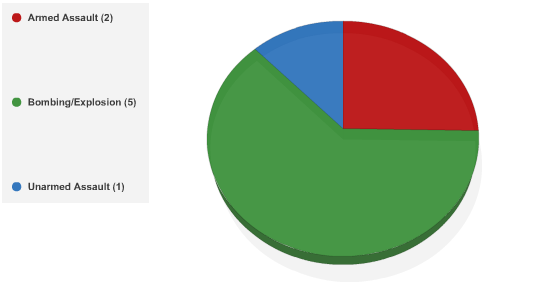

According to Popular Science, the Global Terrorism Database reveals that there have been eight at-marathon attacks since 1994—and only one of them was fatal. Most of the attacks targeted governments and police, while one (a 1994 attack in Bahrain) targeted citizens, leaving three people injured. The type-of-attack breakdown is below:

The attack in Sri Lanka killed 15 and injured 84, while three attacks in Northern Ireland and one in Cyprus resulted in no fatalities or injuries, and one of two attacks in Pakistan (both in 2006) injured four. These numbers are generally uninteresting, especially when related back to what happened in Boston, but they at least show that marathons-as-terrorist-targets isn’t a totally new thing.

“Someone can walk up in the middle of the marathon disguised as a runner or a spectator,” Lou Marciani, director of the National Center for Spectator Sports Safety and Security at the University of Southern Mississippi, told the BBC, “and we have no way of knowing.”

Marciani mentions all the other things—the openness, the vastness, the relative ease of running in the race as a bandit runner—as difficulties in establishing security at marathons. There’s a large, inter-connected team of coordinated groups—emergency responders, university workers, etc.—but they still can only do so much. At the National Sports Safety and Security Conference and Exhibition this July, Marciani expects Boston to be a main topic of discussion.

“This will expand our idea of what a venue means,” he said.

He’s right—but, at least in Boston, the Marathon had been doing that forever.