You don’t have to tell your heart to beat or your lungs to breathe. These actions are automatic. But more than 1 million Americans are stuck with a pancreas they have to operate manually.

They have type 1 diabetes, meaning their pancreases don’t produce enough insulin, the hormone that regulates blood sugar. There’s no cure — only treatment in the form of regular insulin injections, which require diabetics to constantly monitor their blood sugar, or glucose, levels. Few diseases require this much attention, every day, all day.

A handful of researchers in America and Europe aim to change that with a simple-sounding solution: an artificial pancreas.

The ersatz organ is composed of three parts: a continuous glucose monitor, an insulin pump, and a bit of computer software — an algorithm — that acts as the brain, coordinating the other parts to regulate the timing and dose of insulin. A variety of glucose sensors and insulin pumps are already on the market. But those products are “feed-forward” devices, meaning a patient has to program them before meals or exercise to prevent dangerous glucose spikes. That’s especially problematic for the tens of thousands of children with type 1 diabetes, who generally aren’t very good at estimating how many grams of carbohydrates are on their plates.

The artificial pancreas project made a leap forward in 2007 when Frank Doyle, a University of California, Santa Barbara, chemical engineering professor, and his team of engineers developed an interface that allowed doctors to monitor how glucose and insulin levels were changing in the body over time, and let engineers watch their algorithm in action. That enabled research teams to test their algorithms more quickly and easily than ever before.

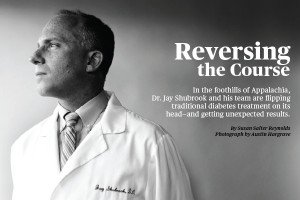

Dr. Jay Shubrook is flipping conventional insulin treatment upside-down — with startling results.

(Click the image to read the story.)

The interface, dubbed the Artificial Pancreas System, is now controlled by a laptop. But Doyle’s goal is to shrink the system into a mobile device for use by the patient.

Doyle’s system is compatible with different types of insulin pumps and glucose sensors, which has encouraged other researchers around the world to adopt it. Boris Kovatchev, a professor of neurobehavioral sciences at the University of Virginia who is working on his own algorithm, says Doyle’s interface was helpful in his clinical trials. Nonetheless, Kovatchev is developing another portable interface, which is currently in outpatient trials in Europe. He and Doyle are awaiting Food and Drug Administration approval to start outpatient trials in the U.S.

If the systems pan out, diabetics will be able to put their insulin supplies on autopilot. “We have a perhaps idealistic goal of getting the human out of the loop,” says Doyle. “We want this to be invisible.”

This article appeared in the May-June issue of Pacific Standard under the title “Digital Relief.”