It’s an uncommon relationship milestone to check your beloved spouse into a hospital psych ward. That is, nevertheless, the scenario writer Mark Lukach confronted in his third year of marriage to his wife Giulia, when she began a battle with severe mental illness. In stories Lukach has written for the New York Times in 2011 and Pacific Standard in 2015, he has documented his life as her caretaker and framed their family’s adjustment to her mental-health struggles as redefining and ultimately strengthening their relationship.

“When we sit down together to discuss medication dosages, or a timeline for getting pregnant, or the risks of taking lithium during pregnancy, we are essentially saying, ‘I love you,'” he wrote in 2015.

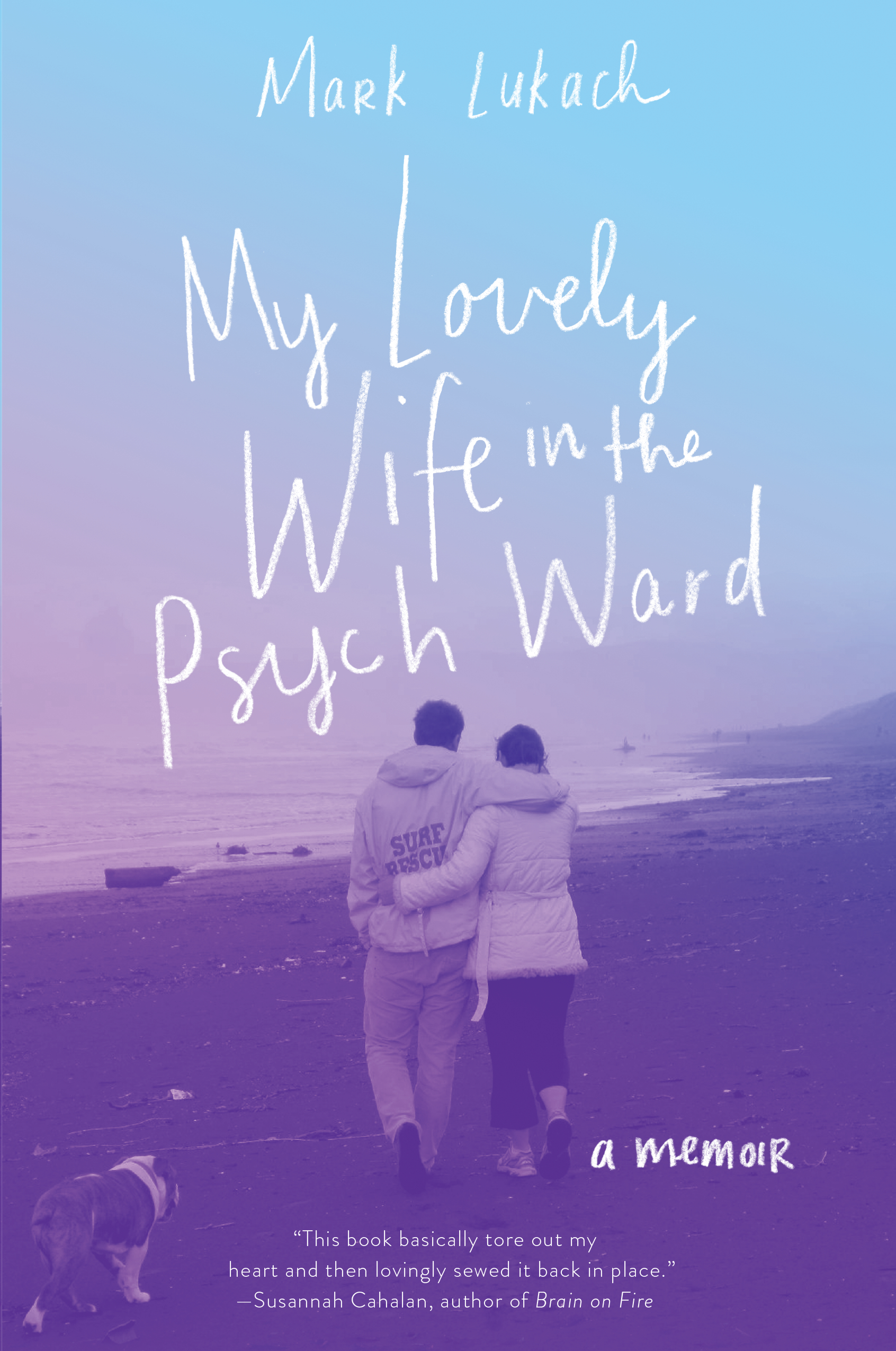

This month, Mark expands upon the couple’s story with My Lovely Wife in the Psych Ward. The new memoir, published in early May, reviews some of the earlier material Mark has written about—his and Giulia’s meet-cute; her two earliest hospitalizations; and the birth of their child, Jonas.

This time, Mark also introduces Giulia’s third hospitalization and foregrounds the couple’s fight to balance Giulia’s health needs with her independence. To help give his wife more control over her care, Mark flirts with a controversial body of research: anti-psychiatry.

Launched in the 1960s among United Kingdom researchers, anti-psychiatry resists medical psychiatry’s definition of mental illness and the treatments it promotes. The field isn’t recognized by all experts—when the University of Toronto, which has the largest psychiatry training program in North America, created the world’s first scholarship in anti-psychiatry last year, some academics protested. Ultimately, though, Mark incorporates just a few of the movement’s ideas into his and Giulia’s plan for her treatment in order to shift their approach to share decision-making more equally than before.

Ahead of the memoir’s publication, Mark spoke with Pacific Standard about the demands of being a caretaker, the family-wide impact of mental illness, and the writing process behind sharing some of the most intimate details of his marriage and family life.

What prompted your first piece about your wife’s health, the 2011 New York Times Modern Love column?

The Modern Love [piece] came out after my wife’s first hospitalization back in 2009. We spent most of 2010 recovering from that. Afterwards, she and I were just in such different spaces. She was like, “Oh my God, I’m better now, I just kind of want to be carefree and not have to deal with any ugly stuff anymore.” I was like, “You’re better now, so someone can take care of me because I had to pretend this wasn’t traumatizing so I could be the strong one.”

The conversation we had was something like, “I think I’m going to try writing this mostly so you can read it, because then you can get a little bit of an understanding of what it was like for me.” I spent a lot of effort trying to understand Giulia and her illness, but she was so consumed by her own illness that [she] had no idea of the behind-the-scenes challenges I was facing.

Another driving motivation for writing this book was how lonely I felt while caring for her. And I don’t just mean that because I didn’t have physical, tangible people around, but because there’s so little literature on caregiving experience for mental illness. There are a couple support groups, but they’re a little difficult, depending on your circumstances, to [access].

(Photo: Harper Wave)

How have your views on caregiving evolved in the last few years, including since the publication of the Pacific Standard article?

What that article doesn’t get into is her third hospitalization. Giulia and I came up with this plan for what we would do [if she had another psychotic episode], where I [would take] the most hands-off approach. That made for her shortest hospitalization, but an even more difficult caregiving burden for me. Once she got out of her third episode, we revived the plan [with one adjustment]. We were like, “Look, if a fourth episode comes along, Giulia recognizes she needs to go to the hospital fairly early on, because it’s not good to be around our child.” And it’s too much for me to try to let her be psychotic around our house when we have a little kid who’s asking questions.

You asked about “my view” [on caretaking], but I would say the better answer is more like “our view.” For the first time, it does feel like our view. For the first time, after the third episode, going through it and then processing it, our views have come to feel like they are a collaboration, as compared to my distinct experience of it and her distinct experience of it. Of course, our days and moments are so different. But we trust each other a lot so that we hold a similar approach to what we want to do.

What was the point after the third episode where you and Giulia found yourselves on the same page, where you said, “We tried a different power balance and some of it didn’t work”?

I think it was because of the tangible successes of her third hospitalization: It was her shortest by 10 days. Now, granted, she was psychotic at home for 10 days, so she was in a similar duration of psychosis, but as far as being in the hospital, it was much shorter.

The other big difference is that Giulia did not have to leave her job. The first time, I was presented with the choice to quit on her behalf or let them fire her, so I quit on her behalf. The second time, she took a very lengthy medical leave, which just ended up with her leaving her job. But the third time, she was able to return to work in a reduced capacity. That told us, something’s right here when you’re in the hospital for a shorter time and you’re still working where you like working.

I don’t know if those successes were because we approached it differently or because of the circumstances, but I do give a little credit for those successes to the fact that we approached the third hospitalization differently.

What do you think are some of the most important differences in the way you treated Giulia the third time around?

When I took her [to the hospital], we had spent about a week discussing whether or not she should be in the hospital. Those are difficult conversations to have when she’s intermittently psychotic. She can’t have those conversations when she’s having the paranoia and delusions. When she’s not in those intense bursts, she’s able to process it a little bit more.

In addition to describing your experiences of being a caregiver in the book, you mention feeling anxiety and depression. Has living through and writing about all of this changed the way you look at your own mental health?

It totally has. Writing this book was really hard but I think it was really important. There’s no question that Giulia’s hospitalization was a trauma, for her and for me. You better believe that writing about this was too—I had to go and relook that trauma in the face over and over again. It was super emotional for me and really draining. I’m a full-time teacher. I’d spend all day at school, come home and pick up our kid, and by bedtime that’s when I would start writing. A lot of nights I wasn’t up for it.

I still get choked up reading about certain things, especially when they pertain to Jonas, but I feel like [writing] it made me more self-aware and therefore in control about how I react to things related to Giulia’s health. I think it’s been big part of me becoming a better caregiver and husband for her. I really had to stew over it: What did I do right and what did I do wrong?

I was struck by how honest you were about some of the toughest points for your marriage. How did you and Giulia together decide which of these intimacies from your life you were willing to share?

I would write something, and she would read it and react to it, and my filter was, basically, if Giulia’s not comfortable with it, I’m not going to push it. If there’s a really important narrative reason for it, I might push it a little bit, I might modify some of the exact details to make it a little more palatable to her, but readers don’t need to know everything about us.

We fought about this a lot. But that was also important fighting. We learned how to communicate. The things we learned while working on this book together have forced us to be nicer and more patient with each other about so many other things. Of course we forget all the time and are impatient and mean to each other. But I think that it’s been kind of amazing—it was like one giant, long couples therapy session and we just had to hash it out.

This process also involved supporting characters beyond you, Giulia, and Jonas—from your extended family members, doctors, nurses, and social workers. What was helpful from those people, and what wasn’t?

My message for the professionals is that mental illness is a shared experience. I wish there was more overt appreciation and support from the professional mental-health world around that. I sought a therapist for myself, but I was never really supported or consoled beyond a few token moments about this being traumatic for me.

For friends and family: If you show up, know you’re not going to fix this, so don’t pretend that you can. The best thing you can do is listen when asked. If I want to talk, let me talk, and hear me out. But if I don’t want to, don’t force me to, because I’m already so exhausted by all this stuff. As hard as that is, you have to support a caregiver with a really open agenda. A caregiver might need to cut loose and be wild or silly; they might need to be really sad; they might need to be really angry; they might need to be specific and detailed; they might need to be vague. If you can have the patience to let them have that, it’s such a gift to a caregiver.

Who out there are you most excited to read this book and your story?

Anybody who’s feeling overwhelmed by a mental-health crisis. I’ve got some emails in response to [my writing] where I read the first sentence and I’m already crying. The person who’s like, “I’m in the ER, I’m Googling ‘psychotic wife,’ and I found your article.” I stop and pause—that’s why I’m doing this. They always end with: “I’m so scared but thanks for doing this. Thanks for giving me something I can relate to.” That’s the audience that I’m really excited to hopefully find this book. I’m not saying this is a blueprint at all, but at least there’s comfort in knowing that there are other people who have done [all this].

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.