On Saturday, November 18th, 1978, Jim Jones stood on a raised platform beneath the tin-roofed pavilion of Jonestown, microphone in hand, and addressed the members of Peoples Temple. About 1,000 members had followed him from Indiana, to central California, and finally to the small country of Guyana in South America. They’d trusted and believed in Jones’ socialist utopia and had sacrificed their time, possessions, money, and family in order to move to and build Jonestown, a socialist, agricultural commune. But that day, Jones told them that everything they’d fought for was ruined. The walls were closing in; there was no escape—a visiting congressional delegation, there to investigate reports of abuse, had left with defectors and then been gunned down on an airstrip six miles from the commune: Their utopia was ruined.

Standing in the center of the platform, Jones described the looming catastrophe and argued that suicide was the group’s only option. When followers protested, he insisted: “I haven’t seen anybody yet didn’t die. And I’d like to choose my own kind of death for a change.” (There have been challenges to the authenticity of the source of this speech, the so-called Jonestown “death tape,” but researchers have generally accepted the tape as an accurate, if fragmented and incomplete, record from that day.)

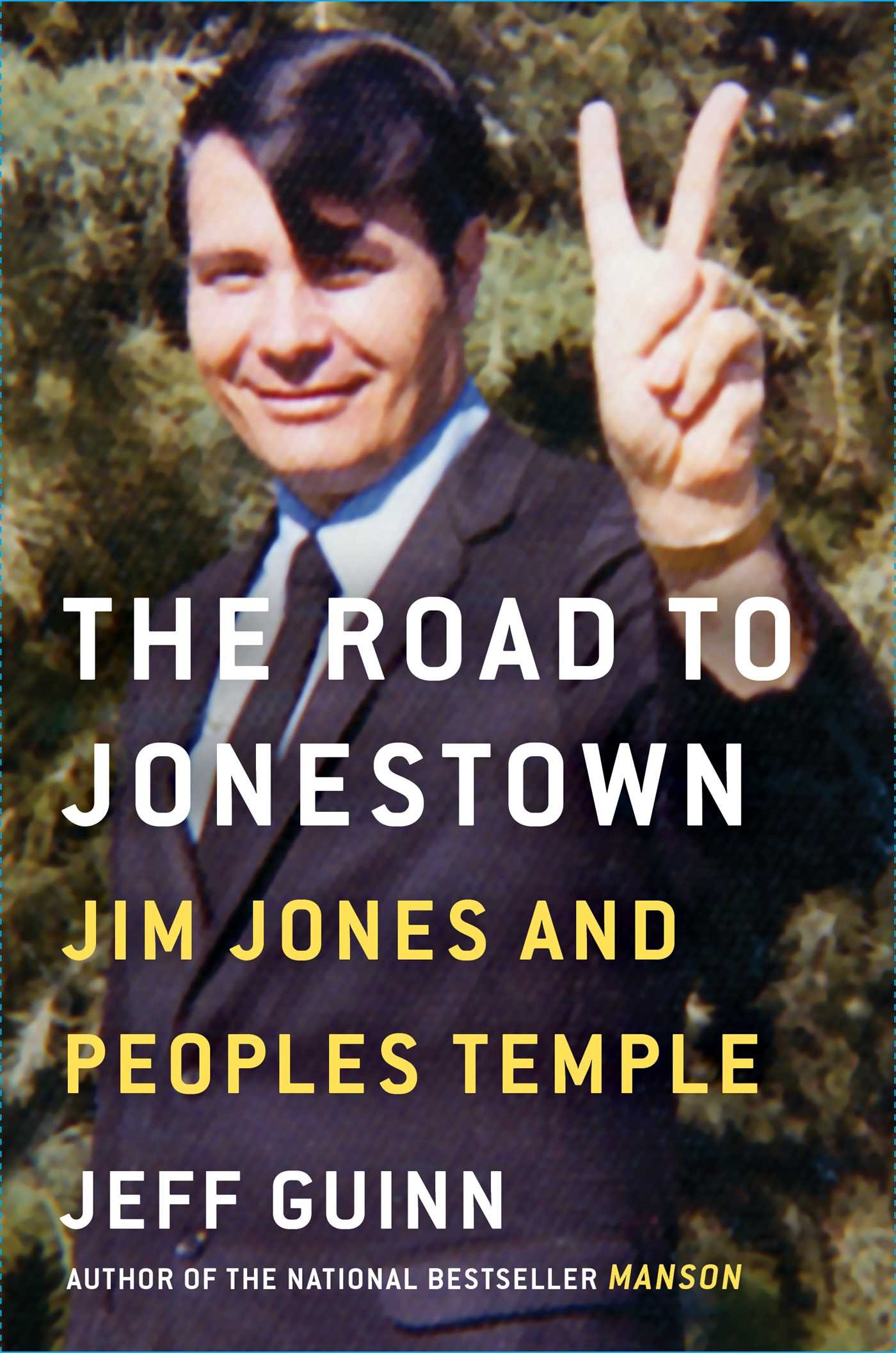

This is the moment that lives in our cultural memory, the moment instantly evoked by referring to “Peoples Temple” or “Jonestown.” But in author Jeff Guinn’s April release The Road to Jonestown: Jim Jones and Peoples Temple, this moment is the final chapter in a long, thoroughly researched examination of the events that led to that day and the followers that stayed with Jones until the end. Guinn gives voice to the shades of belief within the congregation: the followers who genuinely believed Jones was a god, those who saw past his showboating but remained in the church because of the work he did to fight entrenched racism, and those that stayed because they felt they had no other choice. In The Road to Jonestown, the members of Peoples Temple aren’t reduced to the body count, more than 900, found on the floor of the Jonestown compound: They are fully fleshed-out humans, filled with contradictions, beliefs, questions, and potential.

(Photo: Simon & Schuster)

The Road to Jonestown is a rare story about new religious movements (NRMs). Typically, these stories “uphold dominant religious and cultural norms, while marginalizing supposedly strange or deviant religious groups,” Wake Forest University religion professor Lynn S. Neal writes of cult narratives in popular television. Since 1958, media portrayals of cults have evolved from portraying an “exotic and mostly harmless” fringe movement in the ’60s, to solidifying an image of NRMs as uniformly dangerous by the end of the ’70s, on the other side of Jonestown. In a 1977 episode of Starsky and Hutch, for instance, Hutch had to save Starsky from being sacrificed by an NRM leader; The Simpsons and South Park both have multiple cult-centric episodes where characters must rescue family and friends from a mind-washing group; Criminal Minds’ 2008 episode “Minimal Loss” shows two agents going undercover in an NRM to investigate child abuse, and CSI‘s “Shooting Stars” portrays a UFO NRM (modeled on Heaven’s Gate) commits mass suicide. Throughout, stereotypical tenets remain the same—women are loyal followers; NRM leaders are charismatic, authoritarian men; they are deviant and dangerous; they live communally, practice free sex, and stock an arsenal of weapons (like the Manson family, who amassed a cache of grenades, swords, and automatic weapons at Spahn Ranch).

Though it bucks this long-running narrative, Guinn’s The Road to Jonestown is not an outlier in the current pop-cultural landscape: Over the past three years, there has been a resurgence in stories about NRMs that empathetically examine why societal outsiders might be motivated to organize alternative societies. With the release of Emma Cline’s Manson-based novel The Girls last year, along with the airing of NBC’s just-canceled show Aquarius, Lifetime’s Manson’s Lost Girls, the 12 chapters about Manson on Karina Longworth’s popular podcast, You Must Remember This, and Quentin Tarantino’s just-announced intention to direct a feature about the Tate murders, the Manson family is having a pop-cultural moment.

Meanwhile, pastiches of various NRMs can be found in HBO’s The Leftovers and Hulu’s The Path. Scientology has recently been dissected in Leah Remini’s series for A&E, Scientology and the Aftermath, and E!’s 2017 show The Arrangement, loosely inspired by the “romance” between Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes. This trend is not about to wane: Jake Gyllenhaal plans to helm an A&E anthology series about NRMs, beginning with Peoples Temple, and Taylor Kitsch is set to star in a show about the Branch Davidians. These are all expansive stories—80,000 words of a novel, 12 episodes of a podcast, 13 episodes of a TV show—in which writers ask a variety of questions, many large and overarching: Why does this NRM exist and why did its members join? Others are smaller, more nuanced: How complicit are these members in their NRM’s crimes, what keeps them on the compound, and what does the group offer on a day-to-day basis?

There is no easy gloss to these stories and their characters—necessarily, these stories are both barbed and thoughtful. Today, The Leftovers, The Path, and The Girls are, especially, inviting conversations about the circumstances that create NRMs. These titles are suggesting NRMs exist and members join in response to a society they perceive to be neither working nor welcoming: Their government is too caught up in bureaucracy to protect those too poor to protect themselves; parents are ignoring or abandoning their children; mainstream society is myopic and self-serving. At a time when government support systems are falling away and families are finding themselves divided along political lines, these works are giving “cult” characters the motives they’ve historically lacked in popular culture, even as they maintain an old link between NRMs and violence.

The Path on Hulu centers on the fictional Meyerist movement, a religious group that lives on a commune in upstate New York. Members are cultivated and encouraged to ascend the rungs of the movement’s ladder toward achieving personal enlightenment, the movement’s ultimate end-goal. These tenets might sound familiar, but immediately, the show complicates the prevailing narrative of NRMs as dangerous, isolated, and self-serving: The pilot opens with wreckage after a devastating hurricane. People stumble through the hulls of homes, looking for clean water, until a van pulls in and unloads the Meyerists, all wearing blue T-shirts with an eye emblazoned on the chest. The group hands out water bottles, pulls children from the wreckage, and provides medical assistance. The Meyerists seem to have a genuine interest in doing good.

Acts of benevolence can be interpreted many ways in a show about NRMs: Jim Jones fashioned the Peoples Temple into a socialist vehicle that could advocate for those targeted by racism. In her A&E docuseries, Leah Remini insists that joining Scientology felt like an active step toward bettering the world. In some cases, the promise of doing good has lured naïve followers into groups like Scientology (take L. Ron Hubbard’s oft-quoted maxim, “Others talk about a better world. We are making one.”) and Peoples Temple.

(Photo: Hulu)

The Path‘s central character, Mary Cox (Emma Greenwell) is one of many stumbling through the wreckage and is attracted to Meyerism because its members seem charitable. And the movement proves itself to be consistently well-meaning: Meyerism contains many tenets of an NRM: outsiders are “ignorants,” followers live on a compound, marital infidelity is deemed a “transgression.” Characters on the show invoke infamous NRMs like Peoples Temple—one character is jokingly called Jim Jones, another is instructed not to “drink the Kool-Aid”—and the Branch Davidians. But by referring to these events, the Meyerists place themselves at the opposite end of the NRM continuum. They insist: There will be no mass suicide, no slaughter in their movement. There will be safety and there will be homes.

One stereotype that The Path does nothing to push against is women comprising the majority of NRM followers, as well as those most willing to become complicit in the crimes committed by its leaders. As sociologist David Bromley pointed out in a Broadly story last year, NRMs tend to place an emphasis on “issues that are more female-oriented. [These women] like the stronger, more complete answers provided and the attention given to those areas of life.” In The Path, the audience proxy is Mary, who joins after her life is devastated by the hurricane. Before the hurricane, Mary’s life was on a downward track: she was an addict with an abusive father and no steady income—Meyerism provides her with protection. Sarah (Michelle Monaghan), a lifelong member, is unflinching in her support of Meyerism, no matter what lengths she has to go to in order to hide the transgressions of its leaders. After she finds out that the Meyerists’ leader, Cal (Hugh Dancy), has committed murder, Sarah works to cover up his crime so their movement can continue forward. In the world of The Path, women are more reactive than active, taking their cues from the men they live with and following their example.

In the world of The Path, women are more reactive than active, taking their cues from the men they live with and following their example.

Certainly, while recruiting, leaders like Manson targeted women he knew the world had broken, such as Susan Atkins, who had escaped an alcoholic father, and Linda Kasabian, a teenage runaway who was abandoned by the father of her two children: Both were later convicted with the Tate-LaBianca murders. But in infamous NRMs like Manson’s, women have actively pursued their movement’s objectives, from the girls Manson groomed to become murderers to Jim Jones’ wife, Marceline, called “Mother” by the congregation, who provided a softer hand in contrast to Jones’ firm dictates. Many saw her as operating from her heart, a position that reassured them within Peoples Temple, even as Jones’ leadership became more and more dictatorial.

“There used to be a view in the anti-cult movement that people who joined these movements were young, naïve, weak—even damaged,” sociologist Elizabeth Puttick told Broadly in a story about women’s roles in NRMs last year. “Although there was a small minority who fit this stereotype, especially in more traditional NRMs, most people who joined were ‘active seekers.'”

Emma Cline’s novel The Girls focuses on the strong women in a Manson-like NRM—and how they, and not just an enigmatic male cult leader, might draw followers.

The Girls, released in June of last year, follows a 14-year-old named Evie Boyd during the few months she spends as a teenager on a ranch with a “family,” headed by the messianic character Russell, that lives on a compound outside of Petaluma, California. But “it wasn’t Russell, so much as it was a girl” that convinces her join, she says early on in the novel. When Evie meets Suzanne, one of Russell’s devoted followers, Suzanne describes how she perceives Evie to her. It’s an offhand observation, but, for the first time in Evie’s short life, Suzanne makes her feel seen. Evie can disappear from her home and neighborhood for long swathes of time and no one will notice—but Suzanne makes comments when she stays away from the ranch for too long (this is one major discrepancy between The Girls and the real-life events the book is based on—Evie has a family and a place to go home to, but the Manson girls, often, did not).

(Photo: Random House)

Evie is lulled into Russell’s group because he had become “an expert in female sadness,” but it’s Suzanne that keeps her on the ranch. Suzanne cultivates the bond between them, feeding into the adoration she can sense from Evie, braiding her hair, paying her compliments, and teaching her the strange ways of the family. Suzanne serves as an antidote to Russell’s manipulations—he uses the girls as barter, sex for his fame—even as she participates.

Evie senses through whispers and absences that the women have internalized Russell’s directives, his anger against a non-forthcoming fame he felt entitled to, and become violent: She knows there’s a makeshift gun range, and she knows Suzanne has been practicing. Still, Evie doesn’t want to imagine her life without the family while her own family offers a flimsy support system. With Russell and Suzanne, Evie feels solid; she feels a rush of happiness when she’s able to contribute by swiping some money from her mother’s purse.

Expanding on the emotional underpinnings of life in an NRM, The Girls grows the Manson family beyond the cardboard-cutout version of their story, but it can’t undo what they did: However nuanced the portrayal, Russell’s followers still become murderers. A scene Evie isn’t present for, thanks to a final kindness from Suzanne.

To some extent, The Girls relies on a trope that still exists in titles about NRMs: linking religious ideology with violence. Portrayals of religious extremism on TV or in movies shrink the separation between that religion and its extremists; Showtime’s Homeland and Fox’s former show 24 both arguably rely on the fear of Islamic extremism to drive the plot. “Cults” similarly aren’t chosen for story fodder because of their happy endings: No matter what reason one joins an NRM, in pop culture, members often start to believe their leader’s ideologies and participate in whatever doomsday scenario he or she has constructed.

The Girls grows the Manson family beyond the cardboard-cutout version of their story, but it can’t undo what they did.

“Part of what hasn’t changed in the cult stereotype is the idea of the dangerous, charismatic leader, which has become more salient because religion is more associated with violence in the 21st century,” Neal says.

The core demographics for books like The Girls and shows like The Path may factor into the continued survival of the connection between religion and violence. According to a 2015 Pew study, only 41 percent of Millennials say that religion is very important to them, down from 59 percent among Baby Boomers. “People aren’t used to talking about religion and don’t know how to talk about it,” Neal says. Even as contemporary works about NRMs are revealing new psychological dimensions of its members, these characters are still being placed in situations that put them in harm’s way. In this light, these works’ empathy telegraphs as double-sided: Creators are doing more to help audiences understand motives behind joining NRMs, but still aren’t absolving them of a link to crime.

(Photo: HBO)

HBO’s The Leftovers, which just finished its three-season run, also perpetuates the trope of linking religion with violence. In the show, a group called the Guilty Remnant believes their secular society’s lack of religiosity caused the “Sudden Departure,” in which 2 percent of the world’s population disappeared with no explanation. In the wake of these disappearances, the Guilty Remnant—a mute, nihilistic group that chain-smokes and wears all-white uniforms—formed and began amassing members.

Members of the Guilty Remnant aren’t portrayed as the weak, susceptible prey. In the world of The Leftovers, everyone is vulnerable: If you didn’t lose someone to the Sudden Departure, it’s likely you lost them after. Because basic support systems have disappeared, seemingly normal people who would not have been lured into the group before find themselves drawn to its promise of both community and answers; even Laurie (Amy Brenneman), a psychologist and wife of a police officer, with a good life and surviving family members, joins.

The Guilty Remnant is not a perfect answer to the bottom that has fallen out of many people’s lives post-Sudden Departure. The group’s leader, Patti (Ann Dowd) is manipulative and violent; Laurie, Patti’s former counselor, believes in the Guilty Remnant’s mission and relies on it for a sense of purpose, but when a stunt turns to violence and threatens the life of her daughter, she leaves.

Members of the Guilty Remnant aren’t portrayed as the weak, susceptible prey.

Having left, Laurie finds a new mission: rescuing other members. Her son, Tommy (Chris Zylka) infiltrates the Guilty Remnant, looking for those wavering beneath the group’s dogma. But these members’ escape and reintroduction to society doesn’t happen easily. Once Laurie rescues a member, she has a hard time keeping them from returning. Tommy tells her that the Guilty Remnant is “giving them something. We can strip it away, but once it’s gone, we have nothing to put in its place.” So, at a meeting of Guilty Remnant defectors, Laurie offers an alternative to the group: Tommy tells a story about a man named Holy Wayne who passed on his ability to heal with hugs to Tommy. The story is a lie, but, to the group, it comes as a spiritual comfort: something to believe in again.

Perhaps the ultimate benefit to today’s more nuanced shows about NRMs, as flawed as they still are, is that they are prompts for discussion about the conditions that create them. If these more nuanced portrayals of NRMs “don’t give us answers, maybe it gives us possibilities,” Neal says. “It shows there’s a desire to be able to talk about these issues, amid controversy, and understand what motivates people in religious ways. These shows, helpfully or unhelpfully, provide a bridge.”

It’s easy to reduce Peoples Temple to the violent events of November 18th, 1978, but it becomes less easy when you’ve learned the names of his followers and the lengths they went to to preserve their lives, as readers of Guinn’s book will learn. Viewers of The Path may recognize that, from the outside, the Meyerists look like a dangerous cult, but from an interior view, their members genuinely fight to maintain their religion as forward-thinking and humanitarian. The “cult” narrative hasn’t been shattered by today’s works, but it has been complicated. These characters aren’t statistics. They aren’t ghost stories, whispered into the night over a flashlight. They are human stories, with all of their meaty, maddening contradictions.