Are we ready for a national park commemorating the atomic bomb?

A bill to create just such a park, the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, passed the House and is in the U.S. Senate now, with the idea of linking the three places most associated with the development of nuclear weapons into a collective unit open to the public. And the idea is doing better than it did in the last Congress, when the House voted it down.

All told, there are currently 401 sites being administered by the National Park Service, 59 of them “official” national parks like Yosemite and Yellowstone (or Kobuk Valley and Pinnacles) and the balance national seashores, battlefield parks, monuments, recreation areas, and the like. With a few possible exceptions, like Civil War battlefields, all provide a simple narrative—this is majestic, this is fun, this is important, or even pushing the boat out a little, slavery is bad.

The narrative is a little trickier when we talk nukes, even if we’re talking history with a capital “H.” The goal of the Manhattan Project project would be neither to praise nuclear weapons nor to bury them, but to preserve some key sites and “provide for comprehensive interpretation and public understanding of this nationally significant story,” according to the bill spearheaded by Washington state’s Sen. Maria Cantwell.

Adding to the complexity, the three (initial) locales are in three widely separated states, some of the sites are still umm, contaminated, and facilities currently held by the Department of Energy would remain in their remit, with the Park Service offering public education.

The idea of commemorating the bomb’s development at this level has been around for at least a dozen years, and in 2004 Congress directed the departments of the Interior and Energy to study the idea and report back. Two years ago Sunday, the Department of the Interior did so, recommending that Oak Ridge, Tennessee; Los Alamos, New Mexico; and Hanford, Washington, be folded into the prospective park. The Congressional Budget Office in May estimated the start-up costs would come to about $21 million over the next four years.

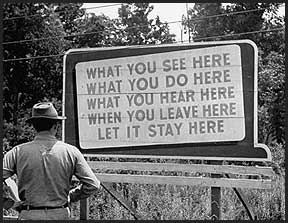

There was a time that Oak Ridge didn’t want to toot its own horn. (PHOTO: PUBLIC DOMAIN)

In a sense, a de facto Manhattan Project park already exists in its constituent pieces. There’s a now 64-year-old Museum of Science and Energy at Oak Ridge, and an interpretive center at Hanford, and the Bradbury Science Museum and Los Alamos Historical Society (the latter alongside the Atomic Heritage Foundation) do yeoman’s work in New Mexico. At Hanford, Reactor B—Easy-Bake Oven for the world’s first plutonium—became a National Historic Landmark five years ago.

In addition, two decades ago DOE designated eight different sites as “signature facilities,” six of them at the three putative park locales. The other two are the metallurgical lab at the University of Chicago, where the first controlled fission reaction occurred, and the Trinity Site 210 miles south of Los Alamos, where the world’s first atomic bomb—dubbed “Gadget”—was tested. The National Park Service already takes care of the ranch house a few miles from Trinity’s ground zero, even though the public is only allowed to visit this particular National Historic Landmark two days—make that one day, thanks to budget cuts—out of the year. In a sense that’s OK; writer S.L. Sanger described it as possibly “the most nondescript of all spots in America where something truly momentous occurred.”

The DOE has long argued these facilities have “extraordinary historical significance”—at the World Heritage Site level—and “deserve commemoration as national treasures. There’s both a certain irony and a certain completeness in suggesting World Heritage status. In 1996 the U.S. abstained from voting to include the Hiroshima Peace Memorial on the list since it was a “war site” and it presumably would lack the historical context of why the U.S. felt compelled to drop the bomb. But at the same time, the State Department suggested an “alpha to omega” proposal that would twin the Hiroshima with Trinity or the University of Chicago lab as a joint World Heritage Site.

Writing about that controversy in a chapter for the book A Fearsome Heritage, Australia’s Olwen Beazley cites conversations he had with a U.S. representative to the World Heritage Committee who cited the brouhaha the Smithsonian had just had over an exhibition of the Enola Gay, the B-29 that dropped the bomb on Hiroshima. At the time, Tom Crouch, curator at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, asked: “Do you want to do an exhibit to make veterans feel good, or do you want an exhibition that will lead our visitors to think about the consequences of the atomic bombing of Japan? Frankly, I don’t think we can do both.” With that mess under its belt—the Smithsonian blinked, canceling the exhibit until a less controversial one could go up—Beazley writes that the U.S. was not against the Hiroshima nomination per se, “but was just trying to protect political interests at home.”

It’s not difficult to imagine the federal government facing similar contortions this time, even with the passage of almost two decades more. “The primary issue in both chambers,” the president of the National Trust for Historic Preservation opined in the Los Angeles Times last month, “remains the concern that preserving and interpreting the Manhattan Project sites would inappropriately celebrate the atomic bomb and the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the close of World War II.” Even with passage of the bill those with ideological axes will have their grinders poised for quick work.

Criticism might this time come more from the left, which in the 112th Congress opposed the Manhattan Project park idea as a form of nuclear cheerleading. “The ‘Bomb Park’ is a mistake. We should not spend another $21,000,000 more to ‘spike the nuclear football,’” former Congressman Dennis Kucinich said last year. “We are defined by what we celebrate. We should not celebrate nuclear bombs.” He argued that any park instead should mark efforts toward nuclear disarmament, and not “admiration at our cleverness as a species.” Given that President Obama is a partisan of both disarmament and the park proposal, perhaps we can acknowledge history and yet still have a future.

As the Smithsonian’s Arthur Molella wrote a decade ago in History and Technology: An International Journal, “Once literally hidden cities, they remain steeped in Cold War culture and ideology, yet they face uncertain futures as weapons production needs change, hazardous waste dangers become more apparent and homeland security is threatened.” But in the end, he saw these facilities as a boon for understanding “the Bomb,” even as anthropologist Janice Harper, in Anthropology in Action, wondered two years later if any nuance might be glossed over in “just another roadside attraction.”

In his new book, The Archaeology of Science, behavioral archaeologist Michael Brian Schiffer argues that there are things to learn from places like Los Alamos beyond the cultural or social navel-gazing that inspires dissent. That practical bent is also observed by Douglas Mercer, who wrote in Museums & Social Issuesthat Reactor B specifically could be a sort of ground zero for talking about nuclear clean-up, “the vita activa of long-term stewardship.”

The just-passed 150th anniversaries of the battles of Gettysburg and Vicksburg suggest that even divisive topics can be dealt with soberly and honestly with the passage of time. Maybe the same will be true now of some more recent, and radioactive, history.