Hill 57 stands at the western edge of Great Falls, Montana, toffee-colored and treeless beneath a gray winter sky. The weather is unusually mild for mid-January, and tufts of grass poke through patches of melting snow. At the foot of the hill, a small blue warehouse has been converted to a tribal cultural center. The building’s dirt parking lot is packed full of cars and pick-up trucks with license plates from across the state.

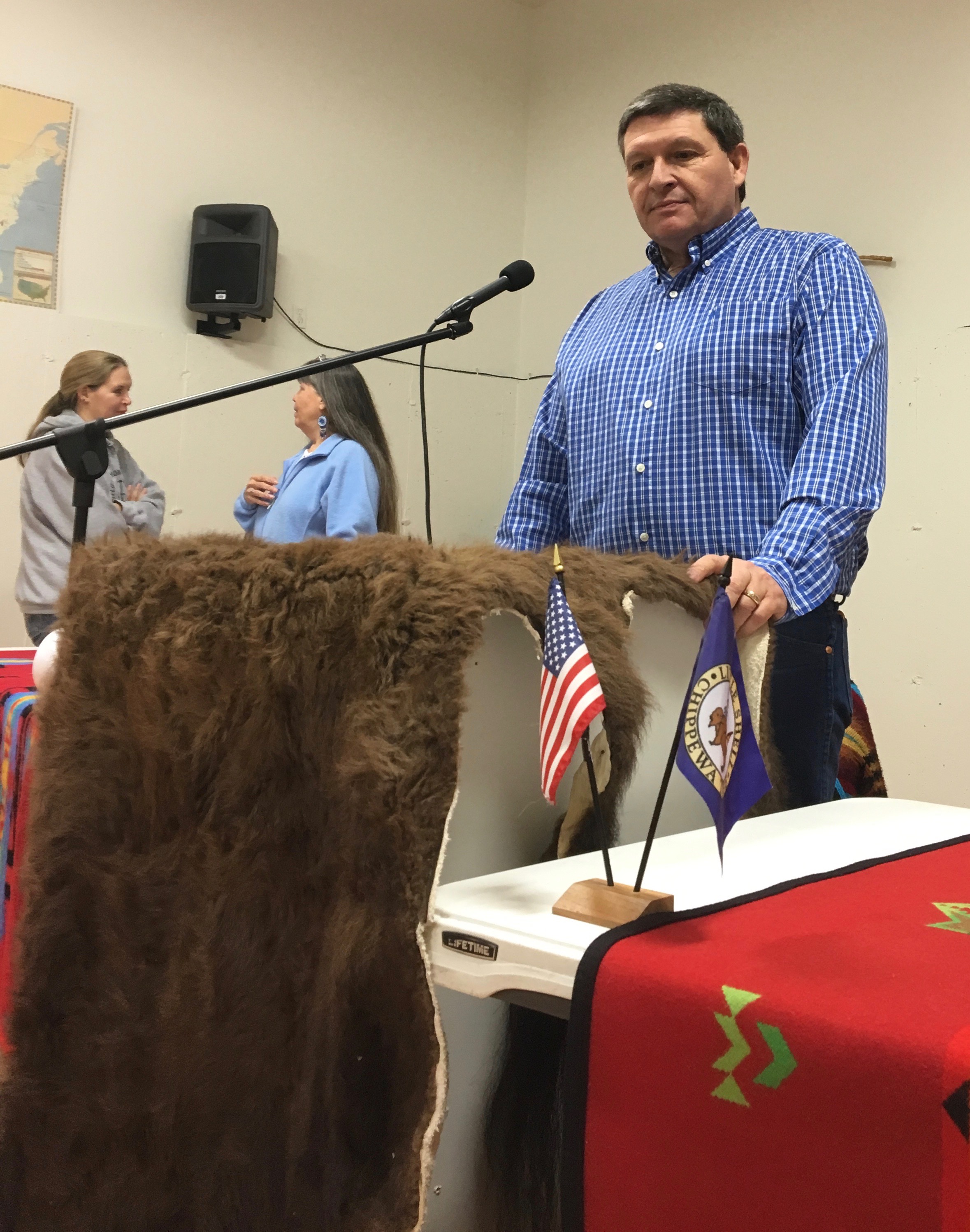

Inside, more than 50 Little Shell tribal citizens have gathered for their first council meeting of the year to discuss their 130-year fight for federal recognition. A dark brown bison robe covers a podium at the front of the room, where Mike LaFountain is preparing to open the meeting with a traditional Chippewa song.

An elk-hide drum in one hand, he searches for his drumstick inside a backpack with the other. “I know it’s here somewhere,” he says. Sitting nearby, Council Chairman Gerald Gray offers him a different stick, which LaFountain accepts with a grin.

Finally, Gray holds up a microphone.

“We’re Little Shell,” he whispers. “We make do.” A laugh ripples through the assembly and LaFountain’s voice, booming and undulant, fills the hall.

The 5,300 enrolled members of the landless Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians have had to make do with no land and few resources for a very long time. Hundreds of tribal citizens began squatting here, at Hill 57, after being cleared from their lands by military force in the 1890s. They camped within a railroad right-of-way where local authorities were less motivated to evict them because the rail company was neither an owner nor active occupant of the land. Today, such homelessness persists in many native communities, where unemployment rates are two to three times the state average of 3.7 percent.

Through these years, the United States has never established a government-to-government relationship with the tribe and has denied its members access to rights and services, such as health care and housing, which the U.S. is required to provide federally recognized American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes as compensation for the loss of ancestral lands. In 2000, Montana recognized the Little Shell, as have the other 11 tribes that reside in the state, but the federal government remains unmoved.

After four generations of struggle, however, there is now reason for hope. In the last Congress, a bi-partisan recognition bill passed the House of Representatives unanimously and came one vote short in the Senate. As a new Congress gets underway, a fifth generation of Little Shell people intends to finish the job.

After concluding his song, LaFountain invited his fellow tribal members to begin this work with a prayer. “I ask creator and all our holy ones up there, our ancestors, to let people see our way,” he says. “It’s our right. It’s our right to be who are.”

In the U.S., there are 573 federally recognized and more than 250 unrecognized tribes; the differences in federal support received by these tribes are like day and night.

“The United States has a trust responsibility to recognized tribes, so these tribes can receive services through the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Indian Health Service,” says Kevin Washburn, who served as assistant secretary of Indian affairs from 2012 to 2016. “The U.S. also has obligations to protect their sovereignty from intrusion by states and other entities.”

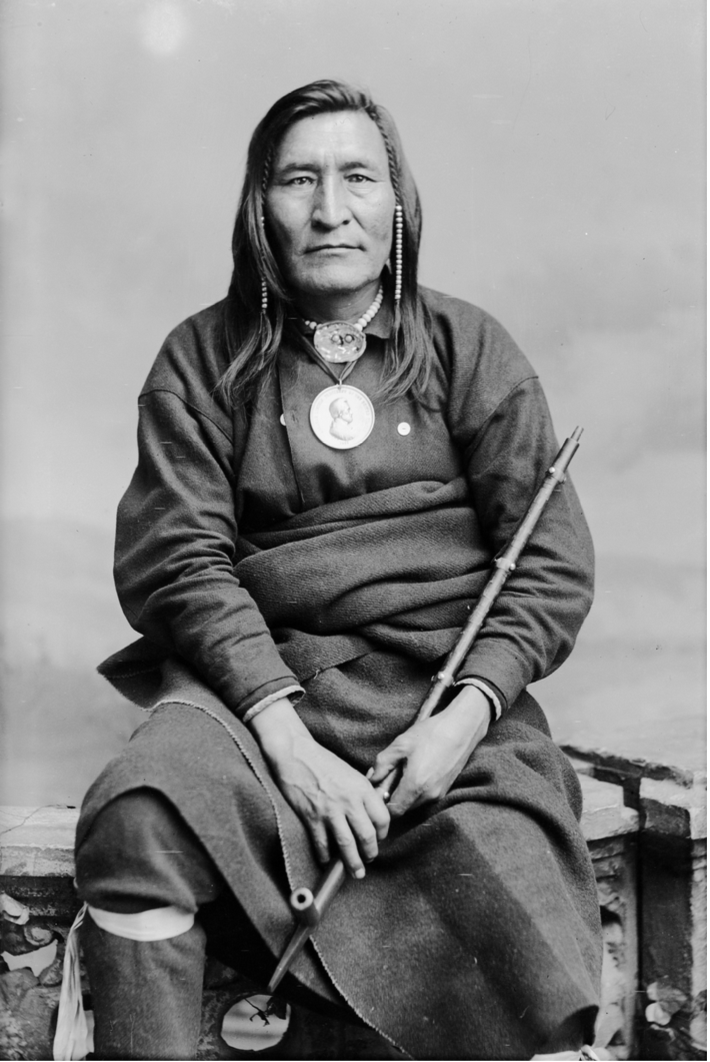

None of these legal benefits apply to unrecognized tribes. For the Little Shell, a polyethnic people primarily of Chippewa, Cree, Assiniboine and Metis (mixed heritage) descent, these rights have been denied since at least 1892. In that year, Chief Little Shell, the eponymously named tribal leader, refused to accept a federal offer of 10 cents per acre for 10 million acres of land, to which they had claim, in north central Montana. That year, the average price per acre in neighboring North Dakota was $3.68.

Congress eventually ratified the treaty, known as the McCumber Agreement, in 1905, without Chief Little Shell’s consent. He opposed it due to inadequate compensation and because of a decision by U.S. negotiators to purge more than 1,400 “half-breeds” from his proposed list of 3,200 tribal citizens who would, according to the treaty, be permitted to settle at the Turtle Mountain Reservation in North Dakota, the historical homeland for followers of Chief Little Shell and other tribal leaders.

This and other federal actions forced Chief Little Shell’s landless followers and their descendants to scrape together a living on the fringes of cities in central and western Montana as woodcutters, shepherds, and domestic servants, among other occupations. “We literally lived in shanty towns and were called garbage Indians,” Gray says.

That de-facto policy of political and economic exile remains intact today. Whereas recognized tribes receive federal support and may form their own governments to protect the interests of their citizens, the Little Shell are on their own. Even now, Gray estimates that a sizable majority of Little Shell families are laborers employed in lower wage jobs.

(Photo: Gabriel Furshong)

“The only way to correct these historical wrongs and restore our dignity is for the United States to once again admit that we are a tribe. All we are looking for is acknowledgment.”

Like all unrecognized tribes, the Little Shell could achieve this goal one of two ways: through the federal acknowledgement process at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which requires tribes to provide extensive historical documentation proving their continuous existence over time, or by an act of Congress.

The tribe first tried the BIA route, submitting a petition to the agency in 1978. At that time, the bureau’s program for tribal recognition was in its nascent stage. “My hope was that the BIA process would provide a scholarly confirmation of the Little Shell’s right to recognition,” says Little Shell Tribal Historian Nicholas Vrooman. But 40 years later, the bureau has yet to render a final decision.

For this reason, the tribe has aggressively pursued a legislative solution over the last decade. Prioritizing Congress over a federal bureaucracy, though, is like swapping a tortoise for a snail. Since 1996, Congress has passed just two tribal recognition bills, including a measure last year that recognized six Virginia-based tribes with a combined 4,400 members.

Montana’s congressional delegation is determined to improve on this record. Senator Jon Tester, a Democrat, first introduced the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians Restoration Act in 2007 and has re-introduced the bill in seven consecutive congressional sessions. Senator Steve Daines and Representative Greg Gianforte, both Republicans, have also championed the bill. “Their case is unique and the Little Shell is important to our state’s heritage,” says Julia Doyle, Daines’ press secretary. “That’s why there is a long history of entire delegation support.” The bill would ensure that federal laws applicable to recognized tribes would apply to the Little Shell and require the federal government to acquire trust title to 200 acres of land for the tribe.

Gray, who, at 52, currently lacks health insurance, believes these legal and material benefits will dramatically improve the lives of his people, but his primary motivation is otherwise.

“People often ask what recognition means to me, and my answer is dignity, plain and simple,” he says. “I spend a lot of time arguing with folks in Washington, D.C., that we are real Indians and a real tribe. There is something deeply painful about having to justify our identity to outsiders.”

This process of identity justification is even more painful when one powerful outsider can effectively refute the history of an entire tribe.

(Photo: Charles Milton Bell; Courtesy of Nicholas Vrooman)

In late December, Gray was in Washington, D.C., meeting with lawmakers when he received an urgent call from a lobbyist letting him know that the Little Shell recognition bill was minutes away from passing.

Gray stepped outside the office building into a light rain pelting the sidewalk. He pulled up C-SPAN’s live feed on his phone and watched as Daines stepped up to a podium on the Senate floor. He held his breath.

“I felt so optimistic that it would finally happen.” Gray recalls. “Then, the air went out of the balloon.”

On what was expected to be the final day of a bitterly partisan Congress, which passed less than 2 percent of the bills it introduced, Daines pointed out that the Little Shell bill had already passed the House and the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs by unanimous consent.

“The Little Shell Tribe has waited for lifetimes. They should not have to wait another year to get this done,” Daines said defiantly. Then, he called for final passage of the bill by unanimous consent, “in the fashion of all the previous votes on this bill, with strong bipartisan support.”

Senator Mike Lee, a Utah Republican, had other plans. Citing the “sacred nature of tribal recognition,” he objected to passage on grounds that, in 2009, the BIA had determined that the Little Shell’s petition for recognition was inadequate. Daines offered a lengthy rebuttal, stating that the BIA had remanded that decade-old determination and was still examining the tribe’s case. But Lee’s objection was sustained. The bill failed.

When asked for comment on this story, Conn Carroll, Lee’s communications director, sent an email that repeated the senator’s claim that the Little Shell case has already been decided. “The Little Shell Tribe went through that process and they were denied recognition by the Bureau of Indian Affairs,” he wrote.

Information from the BIA, however, contradicts this statement and, instead, comports with Daines’ position on the matter. In an email, Nedra Darling, public affairs director for the office of the assistant secretary for Indian affairs, confirmed that the tribe’s petition remains active and that the bureau is currently awaiting supplementary information from the tribe.

This unusually public disagreement between two Republican senators, both from politically conservative Western states, reveals a great deal about the challenges that remain in the new Congress, which convened last month. In the Senate, legislation rarely proceeds by regular order, through committee hearings and floor debate toward a simple majority vote. Why? Because, according to Senate rules, that process requires two ingredients frequently lacking in an uncompromising political climate: a 60-vote super majority and 30 hours to debate a single bill. For this reason, only the most significant national bills, such as defense appropriations, proceed by regular order.

To pass the Senate, then, narrowly focused legislation like the Little Shell bill have to hitch a ride through regular order on a larger bill or pass by unanimous consent, where one objection is enough to kill a bill. Enter Lee, a third-term senator with a long track record of opposition to laws that benefit American Indians.

(Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images)

“I suspect that Senator Lee’s particular problem is not with the Little Shell, but with special treatment of Indians under federal law,” says Arlinda Locklear, former directing attorney for the Washington office of the Native American Rights Fund and the first Native women to argue before the Supreme Court.

Locklear points to several prior occasions when Lee has opposed bills to strengthen native communities and tribal sovereignty. He voted against reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act, which allows tribal governments, under certain circumstances, to prosecute non-Indians accused of violence against tribal members. He also opposed the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Reauthorization Act and has been a fierce critic of the Antiquities Act, which was originally passed to protect native religious and cultural sites.

A member of the unrecognized Lumbee Tribe, based in North Carolina, Locklear worked with Gray to reverse this trend in the waning days of the last congressional session. In December, they met with three members of Lee’s staff in a colorless conference room at the Russell Senate Office Building. “We put considerable effort into answering Senator Lee’s questions,” Locklear says, but, in her view, the meeting felt like “a classic Washington game of whack-a-mole.”

“We would give them material and they would ignore it. Then, they would give us a new set of questions,” she says. “After three or four rounds of this, it became clear [Lee] was running out the clock.”

For some of Gray’s members, the clock is now running dangerously short on time. “It’s frustrating,” he says. “I have to think about all the elders who may never see recognition in their lifetime. Generations are dying waiting for this bill.”

Dan Pocha, 66, is one of the elders on Gray’s mind. He sits in the back row of the tribal council meeting at Hill 57. His short-handle mustache is bright white, and his long dark hair is fading to match. The fourth of nine children, he has attended funeral services for four siblings. Recently, he lost his aunt, Dorothy Songer.

(Photo: Earl Wooldridge; Courtesy of Nicholas Vrooman)

“She died waiting for the day that never comes,” Pocha says. “Sometimes, I wonder if our opponents think, ‘If we just wait long enough, we’ll outlive these people.'”

After Lee’s actions last Congress, Montana’s congressional delegation now seems especially determined to end this wait. Gianforte has already re-introduced the recognition bill into the 116th Congress, and both sides of the aisle remain supportive. If not for the partial government shutdown, the bill might already have passed the House.

Tester and Daines have also re-introduced the bill, which unanimously passed the Senate Indian Affairs Committee again on January 29th. Yet they differ on how to deal with Lee. Daines thinks there’s a chance he will change his vote. According to Doyle, Daines will “be looking at all legislative avenues, whether that is through a stand-alone bill or a larger legislative vehicle.”

Instead of going through Lee, however, Tester wants to navigate around him. “The path is not to bring it forward as a stand-alone bill but rather as part of a larger package,” says Dave Kuntz, Tester’s deputy communications director. “It could be a bill that funds the Department of Interior,” which has jurisdiction over the BIA, while “another option is an Indian Affairs committee package.” This approach would probably lead to a simple majority vote, making Lee’s objection irrelevant.

Whatever the means, Gray feels increasingly certain about the end. He believes the bill will pass and that his tribe will stop making do and start making plans. With the resources made available through the bill, he hopes the tribe can expand their land holdings at Hill 57.

“People always pushed us to the outskirts of town. They didn’t want us hanging around downtown. So, I want to come back here and make this a vibrant area,” he says.

He imagines a new tribal headquarters, a clinic operated by the Indian Health Service, and an enlarged cultural center with educational programs for youth. He wants Little Shell children “to be able to see something that they belong to, something that is their own.”

“I think it will make people feel proud and want to do more themselves for the Little Shell community,” he says. “You always want to do better for the next generation.”