Immigration has long been a crucial issue for Britain—the island nation has a centuries-long, complex history with migrants. Recently, the topic has divided the nation politically: Before Britons headed to the polls last month for a general election, it was one of the biggest issues discussed on doorsteps nationwide. Concern about immigration’s impact on jobs, houses, and services, was the driving force behind why the country voted to leave the European Union by a majority of 52 percent last year, some pundits have argued.

Nevertheless, there remains a gap in the nation’s education and cultural sector when it comes to the topic of people movement. While other migrant hubs, like New York City and Paris, have museums dedicated to the study and history of immigration, the United Kingdom has been missing a similar institution for most of its history. That is, until the The Migration Museum opened in the city in late April. Though it’s currently based in a temporary arts space, the museum is seeking a permanent location.

The museum is the brainchild of the Migration Museum Project, an organization that stages exhibits and workshops across Britain to boost understanding around people movement. Immigration has not been completely neglected by the country’s cultural sector—19 Princelet Street, the Museum of London Docklands, the Huguenot Museum in Rochester, and the Merseyside Maritime Museum in Liverpool also examine migration—but no pre-existing museum looks at “the long story” of migration in the U.K., says Sophie Henderson, an immigration lawyer and director of the Migration Museum. “And not just the story of immigration, but emigration, because over hundreds of years it’s very much been a two-way story of people coming and going.”

In looking at this broad history, the museum realizes the hopes of academics who want the history of people movement to be more widely recognized as part in the national story and dispel misconceptions about migrants along the way. But its founders have a tall task on their hands: The space aims to get everyone to think about their migrant roots, but its challenge will be reaching those who feel far removed the experience of Britain’s newcomers.

The Migration Museum is currently based in Lambeth, a South London neighborhood across the river from the Houses of Parliament and near the headquarters of MI5, the U.K.’s spy agency. Occupying a few simple rooms on the top floor of a warehouse belonging to the London Fire Brigade, its space is far less imposing and grandiose than its neighboring institutions. The rooms look raw, untouched, and a bit unloved, painted white and crowned with dusty, exposed pipes along the ceilings. When I visit on a weekday lunch time, there is just a handful of solo guests making their way around the exhibits, in addition to a press group being given a guided tour.

Entering the Migration Museum past the fire trucks on the ground floor, these visitors are greeted with a quote from author and museum trustee Robert Winder’s 2004 book, Bloody Foreigners: The Story of Immigration to Britain. The excerpt outlines the interconnectedness between recent and longtime U.K. residents that the museum aims to explore: “Ever since the first Jute, the first Saxon and the first Roman and the first Dane leaped off their boats and planted their feet on British mud we have been a migration nation. Our roots are neither clean nor straight: they are impossibly tangled.”

(Photo: Roland Williams/The Migration Museum Project)

Politician Barbara Roche came up with the idea for the museum when she was working as immigration minister for former Prime Minister Tony Blair’s government. During her time in the post, she reignited the migration debate, giving a landmark speech in 2000 in which she called for more immigration at a time when the U.K. had seen a surge in net migration as a result of the expansion of the European Union, and an uptick in people seeking asylum in the country. Having visited migration museums in other countries, such as Ellis Island in New York, Roach—who is of Jewish heritage and grew up in multicultural East London—thought the U.K. needed a commensurate institution. “What we’re attempting to do is to plug a gap, starting on the premise that we all come from somewhere and the only thing that separates us is how long ago it was,” Roche says.

She teamed up with Winder, who suggested in a footnote in Bloody Foreigners that a museum might reduce widespread ignorance on the subject. Henderson joined the group after she got in touch with Winder about the same idea. “It’s important to tell the story [of migration] because what we tend to think unites us is that people, whatever community they come from, generally love a story,” Henderson says.

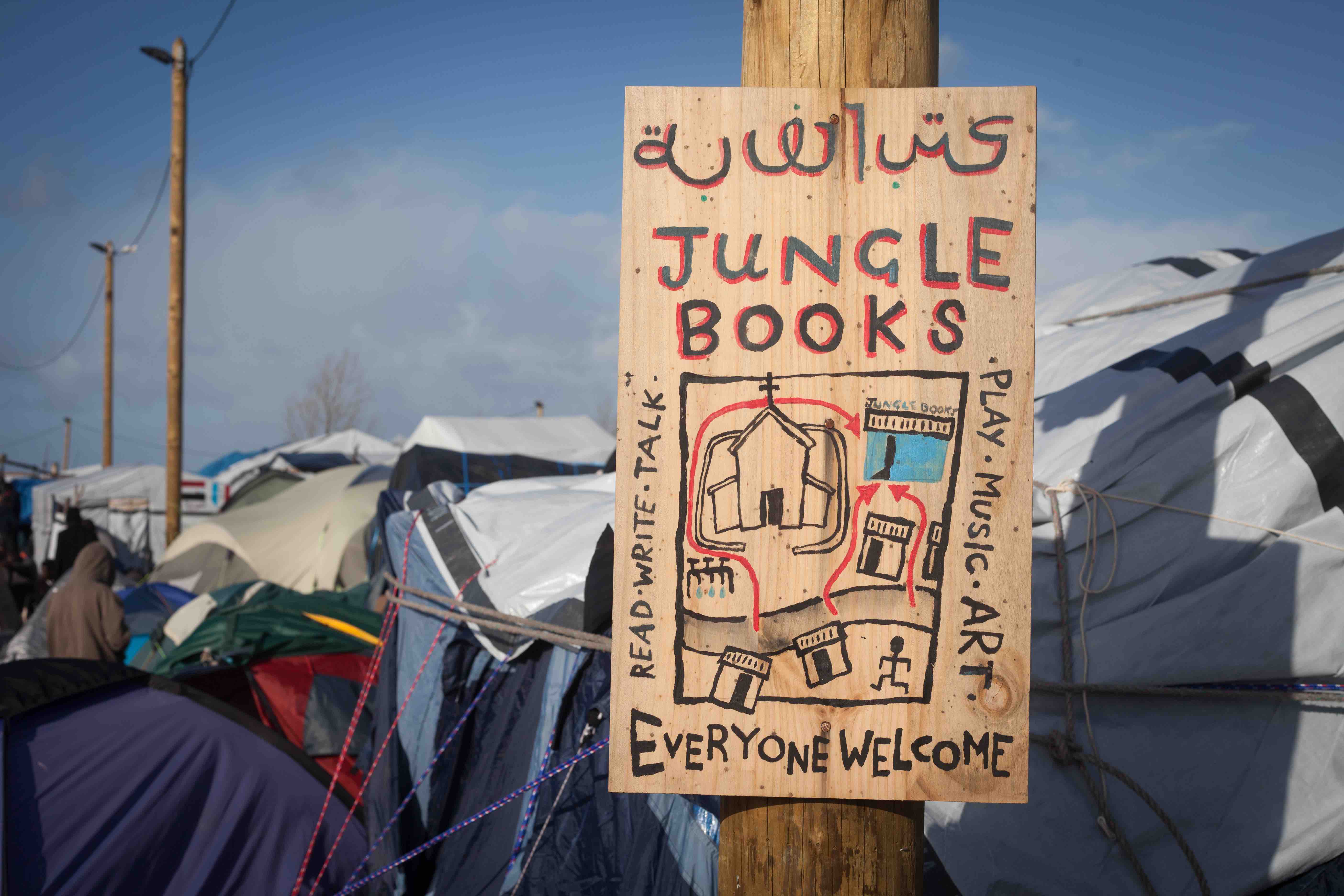

On a Thursday in May, the museum’s main exhibition, Call Me By My Name: Stories From Calais and Beyond, tells the story of refugees living in the makeshift refugee camp in Calais, France, known as “the Jungle.” It displays a collection of paintings, illustrations, photographs, and keepsakes from a settlement that housed approximately 5,000 people of about 20 different nationalities when it was at its largest.

(Photo: The Migration Museum Project)

Call Me By My Name was first shown by the Migration Museum Project at a buzzy pop-up gallery in East London last summer. Since then, the camp has been demolished, but refugees are still coming to Calais, sleeping rough in woodlands, in the hope of reaching the U.K. in the backs of trucks.

The exhibit shows how, together, the inhabitants and volunteers formed a community to make living conditions there more tolerable. The hand-painted sign for “Jungle Books,” the camp’s improvised library, hangs across a wall as a reminder of these efforts. The exhibit also underscores how quickly the camp and its inhabitants, which made headlines and inspired a significant volunteer movement in 2015 and 2016, might be forgotten. A pile of life jackets, collected from the shores of the Greek island of Lesvos, prompts visitors to reconsider the migrants who didn’t survive the journey across the Mediterranean Sea from Turkey.

(Photo: Chris Barrett/The Migration Museum Project)

The exhibition’s organizers have addressed the divisive issue of “the Jungle” by giving air time to both sides of an ongoing debate: Along one wall hangs a series of quotes printed on white cloth from people opposed to the camp, as well as the volunteers and refugees who lived there.

On the quiet afternoon I visit the museum, Marco, an Italian who has been living in London for the past five years, is diligently reading through these quotes. He says it is important to listen to the stories of refugees who come to the U.K. “I’m a migrant myself, and so I see it from a migrant perspective,” he says. “Other people come to Europe to get freedom—it’s a right we can take for granted.”

In an adjacent room, the museum’s other exhibition, 100 Images of Migration, displays a collection of crowdsourced images from professional photographers and members of the public. The photos’ subjects display the diversity of the British migrant experience: a family of British gypsies; refugee children from Vietnam; a British expat bar owner in Spain; a Holocaust survivor from Hungary, grasping the gold pendant she managed to smuggle in and out of Auschwitz. They suggest there is no “one” image of migrants in Britain.

A young couple perusing the photos tell me they read an article about the museum and decided to check it out. “I’m a British citizen and have lived in Singapore my whole life, so it’s nice to learn about my heritage,” says one, named Ben. His girlfriend, Steph, is studying for a degree in public history. “People need to be more aware that migration isn’t a new thing,” she says.

One of the museum’s biggest obstacles will be getting those who haven’t heard about it, or don’t have an interest in immigration, in the door. Since the museum’s temporary space is discreet, it relies on its reputation, and the influence of influential backers including novelist Salman Rushdie and actor Riz Ahmed, rather than passersby, for most of its footfall. A recent evening workshop event, with speakers including Dubs, attracted about 500 guests. The organizers are hoping more events, especially those that engage the local community, will help pull in visitors.

In the few weeks since the museum opened, several groups of students and schoolchildren have also visited, fitting into a framework of immigrant integration that scholars have advocated in recent years.

(Photo: Kajal Nisha Patel/The Migration Museum Project)

Some academics suggest that gaps in the U.K.’s understanding of its migration history stem from its education system. Claire Dwyer, co-director of the Migration Research Unit at University College London, says that some parts of the migration story are better known—such as the post-war period when migrants came to the U.K. from former commonwealth countries. “But other stories of migration are quite invisible, like the long history of Irish migration to the U.K.,” she says.

A move to teach history in a more chronological form, ushered into schools by the government in 2014, has helped to plug these gaps, says Henderson. For the last three years migration has been part of the U.K.’s national history curriculum, which means it is taught in publicly funded schools. “It’s probably something children want to learn about, as their parents will be talking about it,” Henderson says, “but it is not always dealt with very much in schools—partly because it is sometimes seen as a difficult or sensitive issue.”

While many other countries talk about the social and cultural benefits of migration, in the U.K. migration tends to be seen through a “narrow economic frame,” Dwyer says. As the referendum result showed, there is a desire among a portions of the population for the country to “take back control” of its own affairs, rather than allowing Brussels to shape regulations and laws. “What you get—and we are getting even more in the contemporary political era—is a national story that is much more isolationist and much less about being connected,” she says.

The timely opening of the museum in April, though, was pure coincidence, Henderson says. “We are definitely not a political organization and have no campaigning or policy agenda,” she says. Still, as the U.K. enters negotiations with the E.U. for the next two years about how it will leave the Union, and what that means for European migrants, the museum’s core subject area is guaranteed to remain topical.

The ultimate marker of its success in years to come, however, will be if the museum can bridge the yawning and, at times toxic, divide that has emerged within the population based on their attitudes toward migration. A challenge will be establishing a healthy footfall of visitors who, unlike the people I met on my visit, have not thought about their relationship to migration before. This will be no easy task—but, for Britain, it is certainly a necessary one.