My mother still lives in the house where I grew up, so in our frequent talks, she’ll give me neighborhood updates. A few months ago, she mentioned that one of our neighbors—a highly respected emeritus engineer from the University of California-Berkeley—was scammed by a phone call. On the line: a young guy in great distress, claiming to be one of our neighbor’s grandsons and saying that he was in trouble. The neighbor, not an easy man to dupe, wired off a lot of money. Then, not two weeks later, Mom told me about another friend—another retired professor—who was so shaken by a call she received that she, too, sent off a lot of money. We figured someone must be targeting retired Berkeley professors. Maybe through Facebook?

“In stressful situations, worries and distracting thoughts essentially rob people of the thinking and reasoning skills they need to make rational decisions.”

When I mentioned these stories to a co-worker, she told me that someone impersonating her son had called his grandmother, who nearly wired off a pile of money. (The grandmother was stopped by relatives who smelled a rat.) Then another friend said, “My fiancée’s grandmother sent off thousands.” The scam seemed to be everywhere.

My mom has two grandsons, and she started thinking about what she would have done if she got such a phone call. If, for just a millisecond, she feared the call was real, wouldn’t she come to the aid of a grandkid? So many friends have said to her, “That would never happen to me, I would never be duped.” But plenty of perfectly savvy people are wiring money to God-knows-where.

University of Chicago psychologist Sian Beilock, who studies how people perform under pressure, points out, “In stressful situations, worries and distracting thoughts essentially rob people of the thinking and reasoning skills they need to make rational decisions.” With that in mind, my mother became convinced that it was imprecise to assume scammers were getting the best of her friends because 70-somethings were somehow more mentally vulnerable than anyone else. (Spoiler: She was right.) All this to say: We asked my mother (who is also a longtime journalist and author) to write a story for Pacific Standard about why this very personal, and very cruel, deception works so damn well.

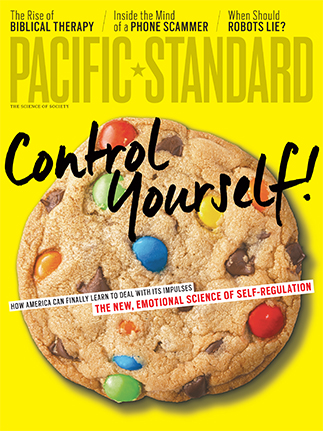

As we were building the stories that you will see on this website over the next few weeks (and that are gathered in our September/October print issue) the notions of deception and trust came up a lot. In “How Should We Program Computers to Deceive?,” which you’ll be able to read here on September 3, Kate Greene delves into the question of how much our computers hide the truth from us—and how much they ought to. In “Unreal Estate: The Art of Scrubbing All Identity From a Home” (which will post on September 10), Kyle DeNuccio explores the expensive artifice of home staging. And in the magazine’s cover story, “A Feeling of Control: How America Can Finally Learn to Deal With Its Impulses” (September 15), the psychologist David DeSteno draws an unexpected evolutionary link between trustworthiness, emotion, and self-control.

So as not to deceive our readers, one more disclosure: Our In the Picture feature (September 24), is about the Indian Trust, a program I worked on in my two years with the Department of the Interior.

Of course, you could subscribe to either our print magazine here, or our digital edition of the magazine via the Apple Store Newsstand here, or—brand new—the Google Play store, here. That way you can get all these stories today (voila, no waiting). We hope you do.

For more on the science of society, and to support our work, sign up for our free email newsletters and subscribe to our bimonthly magazine. Digital editions are available in the App Store (iPad) and on Google Play (Android) and Zinio (Android, iPad, PC/MAC, iPhone, and Win8).