CHICAGO — For the last seven years, Hasan has been in limbo, stranded in the byzantine immigration system where he is seeking asylum because of violence that nearly killed him and threatens his family in the West Bank. He’s spent many sleepless nights weeping, fearing that his wife or one of his three kids has been stabbed or killed back home.

“Why do they keep me for seven years with nothing happening?” asks the hefty, middle-aged Palestinian, whose life has been snared in the United States government’s immigration bureaucracy since 2012, making him an almost mythic example of a troubled system.

Hasan, whose name has been changed for his safety, applied for asylum after arriving in Wisconsin, where one of his brothers lives. His application cited fears for his life back home in a small village near Nablus in the West Bank. Several months later, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services referred his case to the immigration court in Chicago, which covers Wisconsin, Illinois, and Indiana. He has been waiting for a decision ever since.

Hasan is arguing he should get asylum because his family has been caught up in a decades-long blood feud with another family, forcing them at one point to flee to Kuwait. They were later involved in another blood feud with a family close to the powerful al-Fatah faction, which dominates West Bank society, Hasan’s immigration court testimony indicates. On top of these threats to his safety, a memo from the Interior Ministry of the Palestinian National Authority indicates that Hamas, the Islamic Resistance group, issued an order to kill Hasan and his brother for alleged dealings with Israelis.

Nine of his relatives have been killed, including the village mayor, and at least six injured in the conflict, Hasan says.

The June of 2012 document from the Palestinian interior ministry advises the family to leave, saying it doesn’t have the “manpower” to protect it from expected attacks. Hasan has pictures on his cell phone of the injuries suffered by his 11-year-old daughter, who was stabbed on April 17th, 2017, on the way home from school as part of the blood feud. One shows fresh stitches on her neck from a long gash. Another shows a deep open wound in her arm. Hasan’s 17-year-old son had his arm broken and disfigured three years ago. “He hasn’t gone to school ever since,” Hasan says.

Hasan hopes to stay in the U.S. and bring his family to safety here. But without an asylum decision one way or another, he can’t build a new life here or even travel back to check on his loved ones.

Hasan’s long wait, according to his attorney, Omar Abuzir, is nearly all the result of schedule changes and delays that are all too common in immigration court. And by his account, Hasan’s case has been put off eight times over the years. In 2015, 2017, three times in 2018, and twice so far in 2019, he’s prepared for a court date only to have it put off. He had a court date canceled during the government’s 35-day shutdown this winter.

“I don’t know when we are going to be done,” Abuzir says.

Far from the glare and controversy over immigration at the nation’s Southern border, the dealings of the Chicago immigration court offer a compelling insight into what experts say is wrong with the national system: a crushing backlog of cases, long delays in processing them, judges under pressure to make decisions quickly, more stringent yet unclear rules about who should get asylum, and general chaos wherein too many asylum seekers don’t have lawyers and don’t understand the system they are trying to navigate. Months of court observation and interviews with several dozen attorneys, legal rights groups, and immigrant advocacy groups revealed that the court is roiled by long- and short-term problems, many heaped upon it by the Trump administration.

Hasan’s daily survival strategy nowadays is simple: to exhaust himself, to block out his worries. “I like to run and be tired because if I’m awake, I’ll remember what’s happened,” he says. “To sleep, that’s the easy way out.”

People from all over the world, like Hasan, pass through the Chicago Immigration Court. While many immigrants apply for asylum at ports of entry, they often relocate as their cases wind through the court system. Others might evade border patrol or overstay legal visas and make their way to the Midwest.

For those seeking asylum, the burden of proof is high. Immigrants must prove they’ve either faced persecution in their home country or have ironclad reasons to believe they’ll be persecuted in the future without any expectation of government protection.

Immigrants seeking asylum must usually apply within a year of entering the U.S. Those who have been in the U.S. for longer and fear persecution at home can seek withholding of removal—but those cases are much harder to win than asylum cases, and they don’t offer immigrants a path to a green card.

The Trump administration has criticized the asylum process for not being tough enough. But asylum grant rates have already been declining rapidly. The latest figures show that judges denied 65 percent of asylum cases in the last fiscal year, up from 42 percent in 2012.

Immigrants can live for years before getting picked up by local police on an unrelated matter and placed in immigration proceedings. The most common conviction leading to deportation in Chicago’s immigration court, for example, is a traffic-related violation. Immigrants can also be detained following an ICE workplace raid or other operation.

Former Attorney General Jeff Sessions signaled early on that a much harder line on immigration had arrived, telling prosecutors in April of 2017 to get tougher on criminal prosecutions of immigrants. They did, and criminal prosecutions of immigrants saw a marked increase.

A more dramatic shift came in May of 2018 when Sessions declared a zero tolerance policy for immigrants attempting to illegally cross the nation’s borders. The policy said they would be criminally charged and held until their trials. No exceptions would be made for asylum seekers or those traveling with minors. The Bush and Obama administrations had “relatively infrequently” carried out such prosecutions, as noted by the Congressional Research Service.

(Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images)

In 2014 President Barack Obama had said ICE would focus on arresting “criminals, not children. Gang members, not a mom who’s working hard to provide for her kids.”

President Donald Trump wiped such thinking away almost as soon as he took office, and White House officials likened the new policy to taking the “shackles off,” according to news accounts.

One result of the toughened policies has been a marked increase of immigrants without criminal records in the courts.

Nationally, individuals charged only with immigration law issues accounted for 835,000, or 96 percent, of pending cases, as of March of 2019. When Hasan’s first case came up in court, there were just under 400,000 persons in that category. Over 36,000 immigrants without criminal charges were among those with cases in Chicago’s Immigrant Court as of 2019, almost twice as many as in 2012.

A storm of criticism over his policy changes did not dissuade Sessions. Immigrants without valid asylum claims were filling up the courts’ dockets and spending years before coming to trial, he told a group of new immigration court judges last September. It was his responsibility, Sessions explained, “to ensure that our immigration system operates in an effective and efficient manner.”

As immigrants and their families wait nervously in the hallways of the Chicago court, the impacts of the government’s new policies play out day by day. Judges juggle cases and speed up an already breathless process to meet a quota that had been imposed in October by Sessions.

The judges are now required to process 700 cases a year, and to issue final decisions on an immigrant’s case within 10 days of a hearing. They also face penalties if more than 15 percent of their cases are overruled by the Board of Immigration Appeals.

Immigration court judges, immigration advocates, and legal groups have denounced the changes as impractical and unjust.

“This policy further undermines due process and the principle of judicial independence and will subject immigrants who come to the court expecting fairness to an assembly line system,” said the American Immigration Lawyers Association when the new rules took effect last year.

Speaking at a U.S. Senate Committee hearing in May, A. Ashley Tabaddor, president of the National Association of Immigration Judges, said that many judges could not meet the new rules. Many judges, she added, carry from three to five thousand cases at a time, involving complex situations that force them to slate a final trial date from two to four years out.

Indeed, a May of 2019 report from Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse showed that some judges were carrying exceptionally high numbers of pending caseloads: in Houston, Texas, 9,048 cases, in Arlington, Texas, 7,203 cases, and in Dallas, 7,067 cases.

On April 16th, Attorney General William Barr, Sessions’ replacement, expanded on Sessions’ policy, announcing that judges cannot let certain people seeking asylum after arriving illegally out on bond even if they have established credible fear for their lives or safety. That means asylum seekers can be held in detention indefinitely, a major reversal of previous policy.

While creating more hardship, the new policies and new immigration court judges haven’t stopped the backlog from growing.

As for many immigrants caught in the courts’ swelling backlog, Hasan’s anxieties and stress-related health problems grew over time. Reeling from the endless delay, and growing worries about losing his asylum case, Hasan sold his small wholesale business last year, but stayed on to manage it. He didn’t want to be stuck with a business and not enough time to let go without financial losses.

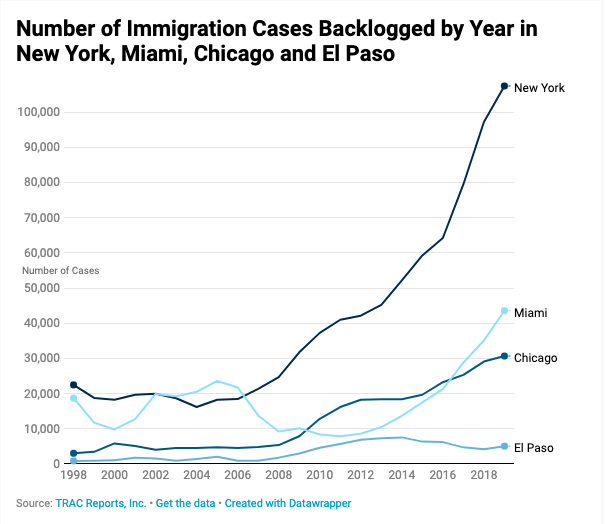

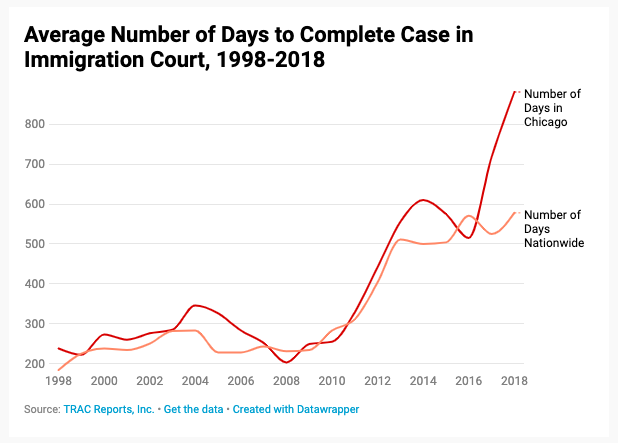

Though Hasan’s seven-year wait for immigration proceedings is considered unusual, long delays are commonplace in Chicago’s immigration court.

The Chicago court’s wait times were the second longest in the nation, tied with the court in Virginia, at an average of 940 days as of April, with 32,444 cases pending according to a recent report by TRAC. With schedules already jammed, the cases missed during the government shutdown last winter are likely to slide to the back of the backlog across the country, says Amiena Khan, an immigration court judge in New York City and vice president of the National Association of Immigration Judges. “I’m scheduling out cases now to the end of 2022,” she says.

The backlog reached 892,517 cases nationally in April, twice the amount in 2014. But that did not include 324,211 cases that had been in limbo since judges and prosecutors considered them “not critical.” Sessions ordered the cases renewed last year, stirring complaints from judges and attorneys alike.

The pile-up of cases is “forcing judges to spend less time on each case and I’m afraid of the quality” of their deliberations, says Robert Vinikoor, a retired immigration court judge who now represents immigrants in the Chicago court. And it is a crisis for immigrants who suffer from the uncertainty about their fate, for those forced to recount the torture or deaths they witnessed or those who have to recreate evidence from events that took place years ago.

The backlog also adds more burdens for the few groups that provide free legal or other services for immigrants going through the process. And it makes immigrants easy prey for unscrupulous lawyers or other actors. “People are vulnerable and they want to hear that there is a solution. So people are easy to take advantage of,” says Mony Ruiz-Velasco, an attorney and executive director of PASO, an immigrant advocacy group in suburban Chicago. More than half of people seeking her group’s help tell of being “misled” or “mishandled” by other attorneys, she says.

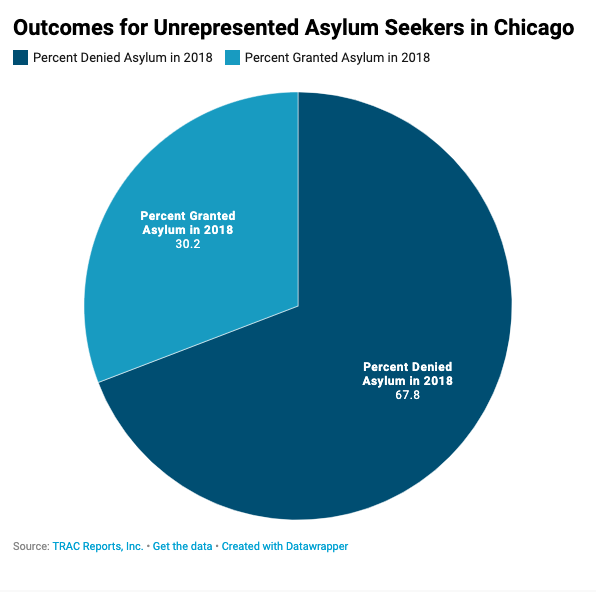

Meanwhile in Chicago and elsewhere, the courts are beset by high numbers of asylum seekers and other immigrants without lawyers, a fate that virtually condemns many to losing efforts. One study of New York City’s immigration courts showed that only 4 percent of those without lawyers win their cases. Of the 199 asylum seekers without an attorney in Chicago, 68 percent were denied asylum last year.

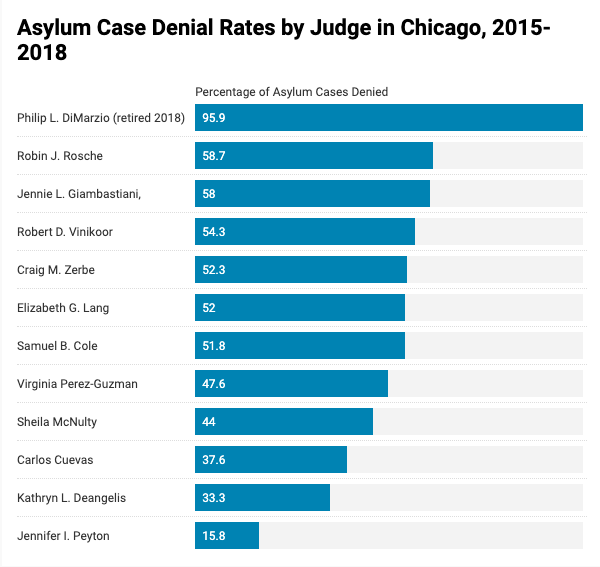

In immigration courts nationwide, including Chicago’s, vast disparities also exist between judges’ likelihood to grant or deny asylum. According to TRAC data, from fiscal years 2013 through 2018, former Judge Philip L. DiMarzio in Chicago denied asylum 95.9 percent of the time. He retired in 2015. During the same time period, Judge Jennifer I. Peyton denied asylum only 15.8 percent of the time.

Such disparities suggest that an immigrant’s fate is bound up with a judge’s politics and background, and the Trump administration has been particular about appointing judges more likely to carry out its hard-line view toward immigrants. Of the 46 new immigration judges appointed by then-Attorney General Sessions in September of 2018, 65 percent of them had law-enforcement or military backgrounds. In Chicago, 40 percent of the immigration judges come from law enforcement.

Listing the immigration courts’ many problems, the American Bar Association recently issued a dire warning. “The immigration courts are facing an existential crisis. The current system is irredeemably dysfunctional and on the brink of collapse,” the ABA said.

On December 6th, 2018, after over a year in an immigration detention center, Miguel, 20, whose name has been changed for his safety, entered a Chicago immigration courtroom before Judge Robin Rosche. Miguel is one of a growing number of Central Americans fleeing violence.

Earlier that year, Miguel’s mother had been assassinated by two men on motorcycles in front of the garment factory where she worked as a fabric-cutter in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, he testified. Marked by endemic poverty, political instability, and gang-related violence, this northern Honduran city has been one of the world’s most violent. Without returning home, Miguel met his brother at the bus terminal and—fearing for their lives—started the harrowing journey to the U.S. to seek asylum.

Miguel was arrested after crossing the U.S. border and put into immigration detention. (Hasan, by contrast, was not held in detention while awaiting his hearings: He applied for asylum after entering the U.S. legally on a tourist visa.)

Escorted by a security guard, Miguel seemed small in the courtroom chair, wearing beige detention clothes and oversized handcuffs. He had no attorney to represent him, much like 23 percent of asylum applicants who moved through Chicago’s courts in 2018 without an attorney, according to TRAC data.

Finding an attorney can be a significant hurdle for immigrants, especially those in detention with little to no money. Despite a robust legal aid community in the city, organizations remain over-burdened and under-resourced.

To obtain asylum, Miguel needed to prove that his life was at risk due to his membership in a particular social group, race, nationality, religion, or political group.

Miguel said that his mother was killed by two members of a gang that regularly sought extortions from her, a reportedly widespread practice across Honduras. Miguel told the judge he could not even go to identify or bury his mother’s body, fearing that the gang members would kill him there.

In June of 2018, Sessions announced that evidence of gang or domestic violence could not generally be used to obtain asylum, reversing an Obama-era policy that it could. A federal judge overruled certain policies based on that decision, but the current legal landscape for people like Miguel remains difficult.

After a one-hour hearing, Rosche denied Miguel’s asylum request. Miguel sat in silence, holding back tears.

As Rosche denied the asylum application for Miguel, another young man from Honduras attended his own hearing upstairs on the third floor of Chicago’s immigration court, in front of Judge Samuel B. Cole.

Javier, whose name has also been changed for his safety, appeared on a video monitor from detention. Unlike Miguel, Javier had an attorney. He also was seemingly luckier in the judge he was assigned, since Cole approves asylum applications at a significantly higher rate than Rosche, according to TRAC data.

Javier testified that, in Honduras, plainclothes police officers beat him and shot him in the foot after his father, who owns a taxi business, didn’t pay his weekly “quota,” or extortion fee to the local gang. Javier’s lawyer argued that Javier and his father were targeted for their participation in the Liberal Party.

Cole disagreed, saying that many in Honduras are forced to pay quotas, not just Liberal Party members. Javier’s lawyer pivoted to argue he was targeted for another type of group membership—that as the son of a business owner, Javier was targeted because of his family.

Javier’s case, which lasted more than twice as long as Miguel’s, seemed to show the value of having an attorney, and possibly a more sympathetic judge.

But ultimately Cole, too, ruled against the young Honduran.

Last October a young Venezuelan mother sat in a corner of Chicago’s immigration court waiting room. As she breastfed her newborn covered by a blanket, her three other children played quietly nearby. Their day in court would be another measure of what immigration attorneys describe as the government’s stiffened approach to dealing with immigrants.

Her Mexican husband had been picked up following a traffic stop in a suburb of Chicago in 2011. Aside from that, his attorney Margaret O’Donoghue said his only crime was crossing the border years earlier. But now he was facing possible deportation, and his family didn’t know what they would do.

The wife had previously been married to a U.S. citizen, so she became a citizen, and all her children were born in the U.S. Her husband was seeking a Cancellation of Removal for Non-Permanent Residents, which requires proving that one’s deportation would cause “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” to a family member. One of the children in the family, a young girl, needs surgery for a cleft palate that the mother said would be difficult to do in Mexico.

Before entering the courtroom with the husband, O’Donoghue had been hopeful. “Not all of our cases are this strong,” she said at the time.

Time dragged on as the case was held in a closed courtroom, and the wife, now virtually alone in the waiting room, grew anxious. “I don’t know where we’ll go,” she said, in Spanish. “Mexico? Venezuela?”

When O’Donoghue emerged several hours later, her expression was downcast. She didn’t think her arguments had gone over well, and was surprised that the government attorney had disputed their hardship plea, arguing that the operation was possible in Mexico.

The judge, who was new on the job, said she would make a decision and mail it out some time in the future.

While the Venezuelan-Mexican family will move wherever they have to in order to stay together, Hasan’s hopes of reuniting his family are pinned on his winning asylum in the U.S. He held up his cell phone recently to play a voicemail his daughter had left for his lawyer on March 22nd. “We are getting tired,” she says in Arabic. “We miss our dad. I want to see my dad.”

And so, he was looking forward to a May 8th hearing that would set the day for a final hearing. He had bought a new suit, hoping to make a good impression on the judge. But late in the afternoon on the day before, his lawyer called to say that he had just learned that Hasan’s hearing had been bumped again, now to October.

Hasan’s blood pressure shot up. He felt dizzy. He wanted to call someone high up in the immigration courts in Chicago or Washington to complain. But he didn’t know who to phone. Despite the bad news, he didn’t even call his family. “I can’t,” he explained, “they have dreams.”

The lawyer later managed to get his final hearing date moved up to September.

Additional reporting was contributed by Miriam Annenberg, Lu Zhao, Ankur Singh, and Kari Lydersen. This story was produced as part of a partnership with the Social Justice News Nexus at the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University.