A specter is haunting American journalism.

Rolling Stone has apologized for its now-retracted coverage of a rape case at the University of Virginia, its failures meticulously catalogued by the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, and duly highlighted on the front page of the New York Times. Like a snake devouring its own tail, much mainstream investigative journalism today chronicles the shortcomings of its colleagues to follow minimal procedures of reporting.

Covering the Rolling Stone debacle on the Daily Show, Jon Stewart could only joke about the absence of any official repercussions at the magazine, and took upon himself a “citizen’s firing” in lieu of the magazine’s failure to discipline anyone associated with Sabrina Rubin Erdely’s December 2014 article “A Rape on Campus.” While this inaction has further damaged Rolling Stone’s credibility, more egregiously, Erdely’s account sets back the cause of students sexually assaulted at American universities and seemingly provides absolution for a fraternity system many argue lies at the center of campus dysfunction.

While plenty of documentaries are available on HBO, PBS, and Netflix, many others show only at specialized film festivals. Unless they’re released online for free, they never reach the audiences they merit.

What else can any of us do but laugh through our outrage?

And yet, the Rolling Stone episode, grotesque as it is, provides just another example of the overall decline of investigative journalism in American media. Buffeted by the digital revolution and corporate decisions to convert news departments into revenue streams—including CNN dropping its entire investigative reporting team in 2012—mainstream journalistic outlets have sacrificed muckraking on the altar of bottom-line profits, leading to a plunge in standards. As of 2013, all the investigative reporters at the Miami Herald had left for other jobs.

While one may highlight any number of instances when this decline accelerated, the landmark was the collaboration of the New York Times in the Bush/Cheney administration’s selling of the invasion of Iraq. Reporter Judith Miller led millions of American readers—legislators, corporate leaders, fellow media producers—on a wild goose chase for non-existent weapons of mass destruction.

American correspondents, in bed and embedded with the military, faithfully reported the United States government’s version of events for months until the futile search for WMDs deteriorated into a reality show manhunt for Saddam Hussein. George W. Bush—together with a compliant U.S. Congress and “free press”—deserves responsibility for creating the ashes from which the phoenix Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant has risen.

As reliable investigative journalism seems to be fading into non-existence, with sometimes catastrophic consequences, what is to be done?

Into the void have stepped documentary filmmakers, themselves equipped with new digital tools, on budgets often as small as the cameras with which they shoot and the computers on which they edit. Some of the most thoughtful American coverage of the chaos in Iraq emerged from independent filmmakers like then-31-year-old James Longley.

At his own expense, equipped with a $3,500 camcorder, Longley traveled to Iraq beginning in 2003 to report Iraqis’ versions of the destruction of their country in his feature documentary Iraq in Fragments (2006). Trained at Wesleyan University and the Russian State University of Cinematography (VGIK), Longley filmed solo on location, without security detail, for two years. With function following form, the movie prophetically breaks into three sections devoted to the disparate experiences of Shiites, Sunnis, and Kurds. The boots on the ground are decidedly those of Iraqi civilians. The MacArthur Foundation recognized Longley’s artistry and integrity in 2009 with a deserved Genius fellowship.

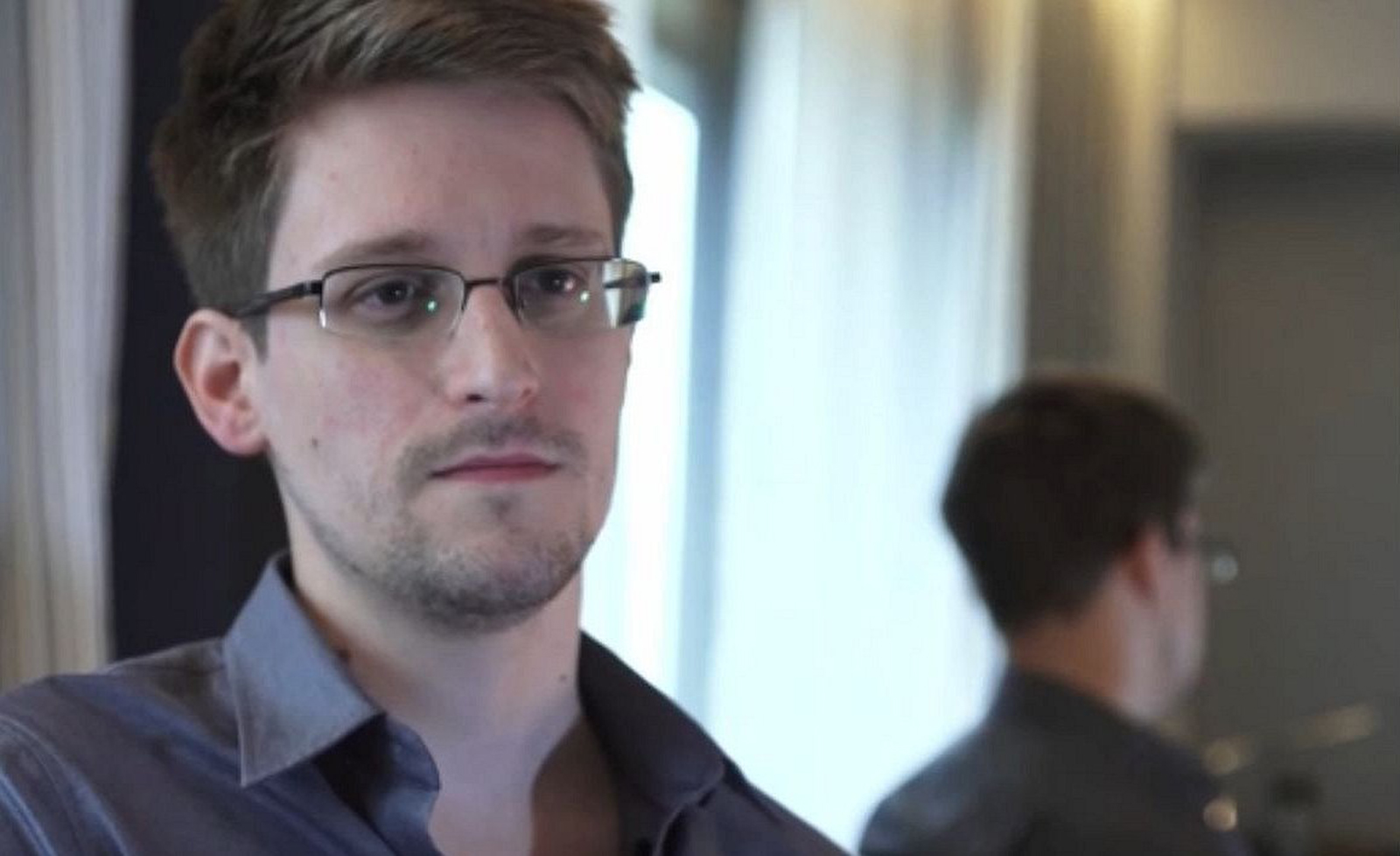

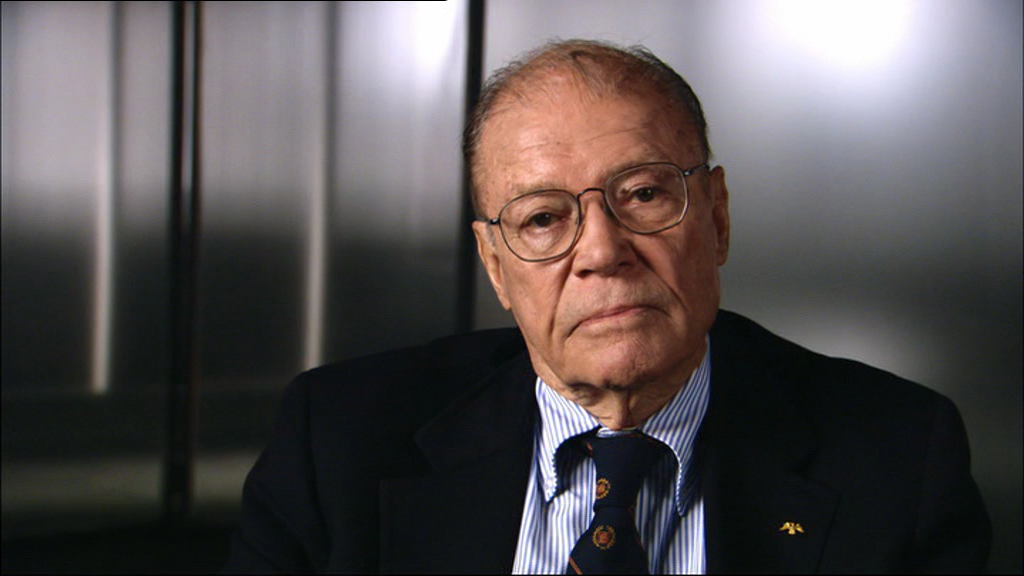

An exemplary investigative journalist, documentarian Errol Morris, in The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons From the Life of Robert S. McNamara (2003), pursues an American secretary of Defense’s heuristic recapitulation of the U.S. war in Vietnam. In Inside Job (2010), Charles Ferguson pinpoints the complicity of American university economists in the collapse of the world banking system. More recently, Laura Poitras’ Citizenfour (2014) demonstrates the ubiquity of the new security state set into motion by George W. Bush and wittingly carried forward by President Obama.

Poitras, an American citizen, currently lives in exile in Berlin after being put on a secret watch list and repeatedly harassed by U.S. immigration officials, like the American journalist Glenn Greenwald, ensconced in Brazil, who helped expose U.S. surveillance programs, and, of course, whistleblower Edward Snowden himself, currently holed up in Moscow. The extent of U.S. governmental surveillance is the new “known unknown,” as Donald Rumsfeld put it in a very different context, “things we know we don’t know.”

For each of these high-profile Academy Award nominated or winning documentaries, there are hundreds of worthy non-fiction films produced every year, some by trained journalists, others by self-taught independent filmmakers, who spend years in passionate pursuit of injustices committed at home and abroad. While plenty of documentaries are available on HBO, PBS, and Netflix, many others show only at specialized film festivals. Unless released online for free, they never reach the audiences they merit, and, even if purchased for broadcast, such documentaries rarely return sufficient revenue to cover a fraction of their costs.

While documentarians have resolutely supplanted the dwindling numbers of investigative journalists at print publications and traditional media outlets, their films don’t receive the distribution they deserve, thus leaving citizens in the dark about public affairs. Admittedly, written investigative journalism has not disappeared, thanks in part to the support of The Center for Investigative Reporting, The Investigative Fund, and ProPublica. To its credit, the New York Times’ Op-Docs video channel streams independently produced shorts that tackle important issues, but—and here’s the catch—the Times pays only a token amount for showing the videos.

We need an online channel to financially support and distribute the now irreplaceable feature work of independent documentarians. Is there anybody out there, Jon?