Even now, several years later, Rebecca Cervenak can still remember what the inmate, standing half-naked in a white, rubber-padded room, said to her. “He was talking to me through the solitary door,” she recalls, “and he told me: ‘You’re the first person who’s looked at me like I wasn’t an animal. Like you actually saw me.'”

While the moment sticks out to her, it was anything but atypical. As a staff attorney for Disability Rights California, a non-profit agency that advocates for people with disabilities, Cervenak was part of a team investigating inmate suicides in San Diego County Jail. The prisoner who spoke to her was one of dozens of such inmates.

The DRC team had set out to create a broad report on conditions in San Diego County Jail. Once the research began, however, there was one particular data point that jumped out at her: “When we first went in, we were looking at solitary confinement and use of force, but also at accessibility for wheelchairs, deaf people, that sort of thing,” Cervenak says. “But what stuck out to us in San Diego was the high suicide rate.” After years of research, their report finally published in April of 2018.

DRC investigators found that, with more than 30 suicide deaths since 2010, San Diego County Jail has had one of the highest incidences of suicides over several years. They also identified significant deficiencies in the county’s suicide prevention practices.

As the DRC team investigated incarceration practices on mentally ill inmates in the San Diego County Jail, they recognized several warning signs in the methods by which the jail disciplined that segment of its population.

Cervenak and her team were struck by the jail’s tendency to place mentally unstable inmates for extended periods of time inside “Safety Cells,” white rubber rooms that feature padded walls and a grate in the ground that functions as a toilet. “That way they can’t hurt themselves,” Cervenak tells me.

San Diego County Jail places actively suicidal inmates in these Safety Cells until they can be evaluated. This type of isolation is common in county jails and, in theory, should only be used in the most extreme circumstances.

“We don’t want people in these cells for more than a couple hours. If they qualify for a higher level of psychiatric care, they should be transferred to inpatient care,” Cervenak says.

Records reviewed by DRC investigators showed that many inmates are held in Safety Cells for much longer than 24 hours, and in some cases up to four days. San Diego County Jail has no official time limit for how long an inmate may be kept in a Safety Cell.

“This treatment is worse than people treat animals…. Being locked in jail inside a box inside of another box can do things to a person’s mental state,” one woman wrote in a grievance she filed after her unit faced its tenth lockdown in two weeks.

DRC quoted a psychiatrist’s report examined during their investigation that called the isolation “inhumane.”

Safety Cells were just one of many jail policies investigated in the report; others included Psychiatric Safety Units and Enhanced Observation Housing Units, which give inmates a bed, but all clothes and underwear are taken away save for a safety smock, two blankets, and shower shoes. However, DRC reviewed multiple records documenting that EOH inmates were left naked, with no safety smock.

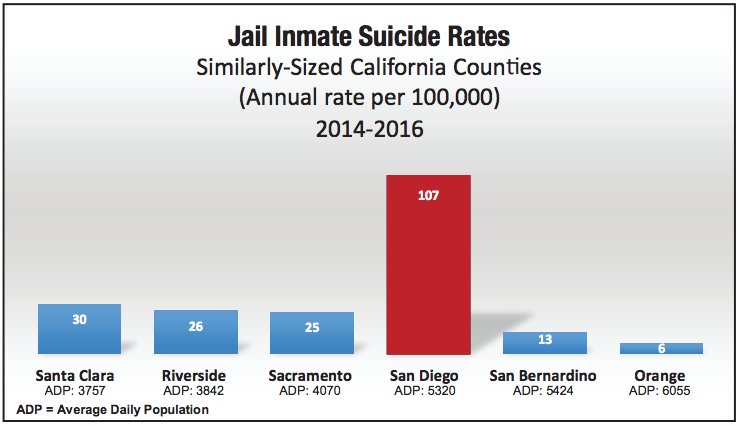

The data that DRC compiled suggests San Diego County Jail’s average suicide rate in the years 2014–16 was approximately 107 per 100,000 inmates, a shockingly rate compared to California’s 10 largest jails. The report would suggest that the county is failing its population of inmates and needs to re-evaluate its suicide prevention system.

But San Diego County conducted its own analysis and reached a far different conclusion: After hiring a private statistical consultant to rerun the very same numbers, the county determined it did not have a significantly high suicide rate compared to California’s 10 largest jails.

The DRC report alleges negligence on staff and officials’ part; the county’s report alleges San Diego County Jail does not have a suicide problem.

So, why is there such a disparity in each side’s conclusions?

The DRC report has at least one piece—several pieces, really—of corroborating evidence: a spate of private lawsuits against the county, many of which agree with DRC’s version of events.

In one such lawsuit, Chassidy NeSmith, whose husband committed suicide in 2014 in Vista Detention Facility, a detention center in San Diego County’s jail system, sued San Diego County and Sheriff Bill Gore in 2015. The lawsuit alleges that, despite being warned that NeSmith’s husband had attempted suicide several times, jail commanders and deputies made little effort to implement harm prevention techniques.

A federal judge then held San Diego County in contempt of court for refusing to comply with an order to turn over documents requested by the plaintiff, contributing to the long wait for NeSmith—the case has dragged on for years and is still ongoing today.

“[The county] is on notice that there were defects in suicide prevention practices there,” Cervenak says. She believes there are financial motivations behind the county’s retaliatory report—namely the lawsuits, which she speculates are “a big financial burden.”

“They should be spending their money fixing their problems instead of hiring experts to calculate different rates,” she says.

Christopher Morris, an attorney in the NeSmith case, told the San Diego Union Tribune in May of 2018 that county lawyers were reluctant to turn over documents related to the case because “they are likely to show that Gore and other officials were aware of the suicide problem in San Diego County jails and did little to correct it.”

Using a new analysis of the San Diego County Jail suicide rate could help the county in the NeSmith case and others by alleging that officials were not aware of how pressing the problem was.

“We have to prove the county was on notice that its suicide policy was deficient,” Morris said. “From the highest levels in the county, they knew this was a problem.”

In April, the DRC investigative team published the report summarizing stories similar to NeSmith’s and the rest of its findings on the San Diego County Jail, calling it “a system failing people with mental illness.”

In one case, DRC investigators found that an inmate was booked who displayed acutely manic and psychotic symptoms (he had been hospitalized twice shortly before his incarceration). Yet still, it took the jail two days after he was booked to give him a psychiatric evaluation and the appropriate medications. A nurse practitioner recommended that he be placed in a safer, more closely monitored space based on his condition; however, a sergeant refused to move him. He remained in an Administrative Segregation Cell, where he died by suicide that evening.

San Diego County Jail officials did not respond to several requests for comment, except to send a previously written response to the DRC report.

San Diego County Jail really went wrong, the DRC says, in its use of “enhanced observation housing” for people who don’t need to go in a safety cell, but who still worry jail officials. The enhanced observation cells are similar to a typical cell: There’s a concrete bed, a desk, and a toilet with no tile points. The difference is that in this case all of the inmate’s personal property—including clothing—is removed and replaced with a “safety smock.”

“People were in these cells for sometimes weeks at a time,” Cervenak says. “That was the first time we’d seen anything like this.”

The report caused a stir in San Diego, already plagued from a 2014 article citing San Diego County Jail’s high suicide rate. The jail responded to the DRC investigation by publishing its own interpretation of the DRC’s data. The county hired a statistical consultant, Colleen Kelly, to re-run the numbers. Kelly is a statistical consultant and a former professor of statistics at San Diego State University.

Kelly declined several requests for comment.

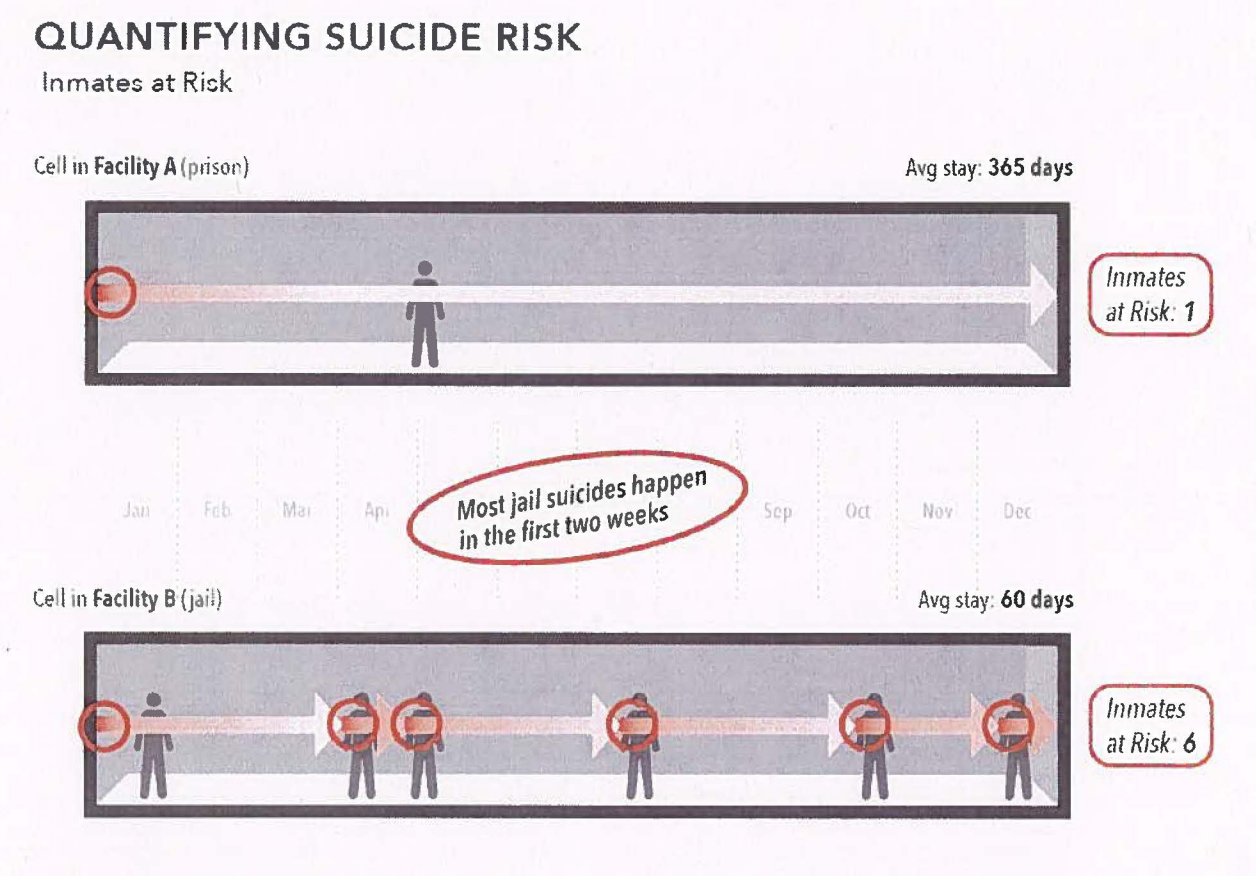

In her report, Kelly calls the DRC’s method of calculating suicide rates “flawed” because it used the average daily population (ADP) rather than the number of inmates at risk to calculate the suicide rate. This means that, in jails, which have high inmate turnover rates, using ADP often “double-counts” inmates in calculations that use an inmate’s yearlong stay as a denominator.

Though ADP has been the methodology historically used by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Kelly writes that “[c]omparing the average daily population (ADP) suicide rates across jails with differing numbers of inmates at risk is not a fair comparison; one should expect higher numbers of suicides in jails with larger numbers of inmates at risk.”

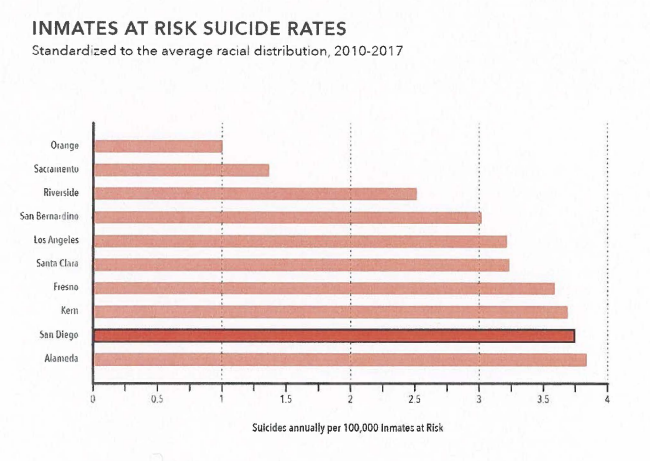

Kelly finds the data further flawed because it does not account for the racial make-up of San Diego County Jail, especially compared to other county jails in California. San Diego had the highest percentage of white inmates (46 percent) of the 10 largest jail systems in California between 2010 and 2016.

White inmates—and white people in general—have a higher risk of suicide. A 2010 study on jail suicide found that 67 percent of jail suicide victims were white, 15.1 percent were black, and 12.7 percent Hispanic. Kelly accounted for racial demographics in San Diego County Jail and other large California jails, determining that San Diego did not have a “significantly different” suicide rate compared to California’s 10 largest jails.

Perhaps Kelly’s findings mean that, mathematically speaking, it’s not fair to demonize San Diego County Jail for its high number of suicides. After all, the jail’s population has a higher proportion of at-risk inmates than most jails its size.

Fifteen of the 17 suicides DRC examined in the three-year investigation period from 2014–16 were pre-trial, Cervenak says. “So they’ve been charged and either denied bail or can’t afford bail. Technically, they’re still presumed innocent under the Constitution because they haven’t been convicted of a crime.”

Presumed innocence is sometimes not enough to hold on to for people who are already mentally unstable or in need of medical assistance.

Although the county managed to prove that its jail’s suicide rate was not drastically different from other counties’ rates, concern for inmates with mental-health issues remains.

“The fact that San Diego County may have a higher-than-average number of inmates at elevated risk of suicide only adds urgency to the need for action,” the DRC report says.

Suicide rates and calculations aside, more than 100 detainees have died in San Diego County custody since 2010. At least 30 of those have been attributed to suicide.

“Just the raw numbers compared to the other counties is astounding,” Cervenak says. “We can spend our time arguing about suicide rates, or we can start working on trying to solve the problem.”