In one tiny city in Northern California, a land dispute that’s ensnared Japanese-American advocates, the small municipal government, and a Native tribe appears to be headed to court.

Japanese-American community leaders plan to take Tulelake, a predominantly Republican city, to court over plans to sell the site of their elders’ World War II incarceration to a Native-American tribe. And they’re mounting their legal battle as Congress is set to decide whether to continue funding for similar sites commemorating the government-mandated collective punishment of an American immigrant community.

The Tule Lake Committee, an advocacy group for the descendants of people incarcerated at the Tule Lake wartime concentration camp, tells Pacific Standard it is preparing next steps this week in an ongoing legal showdown with Tulelake municipal authorities, which plan to sell 358 acres—more than half of a site where tens of thousands of Japanese Americans were incarcerated—to the Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma for $17,500.

An executive order by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt incarcerated more than 120,000 people of Japanese-American origin during World War II at 10 concentration camps across the country. The Tule Lake camp was named for an adjacent lake, located near Tulelake city.

The region is the ancestral home of the Modoc Tribe, a large proportion of which was violently displaced by settlers and eventually relocated to Oklahoma. A recent Modoc tribal newsletter describes the purchase of the Tulelake Municipal Airport, which the tribe says will continue to operate as an airport, and another land parcel in that region.

In its court filings, the Tule Lake Committee cites that the tribal buyer has been implicated in allegations of fraud. In June, the Modoc, together with the Nebraska Santee Sioux, agreed to pay the government $3 million for its alleged role in a payday loan scam involving former race-car driver Scott Tucker, Bloomberg reported.

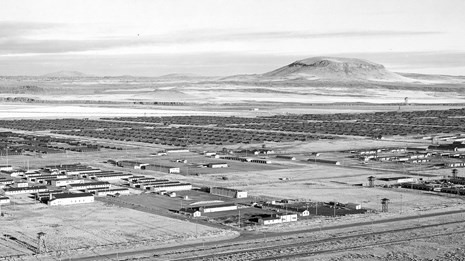

(Photo: National Park Service)

Last week, a United States District Court judge ruled against the Japanese-American Tule Lake Committee’s bid to temporarily restrict the sale, which, barring government intervention, would be finalized at the end of August. Tulelake authorities were mulling a bid late last year to replace a small fence around the airport with a more robust eight-foot-tall, three-mile gate with the stated aim of blocking wildlife from the tarmac. The Japanese American Tule Lake Committee members said that the safety measure would also bar future generations from visiting the site of their elder’s incarceration.

Tule Lake Committee Chief Financial Officer Barbara Takei says that her organization tried to bid against the tribe and has offered to actively help to develop the local economy in exchange for allowing the descendants of the Tule Lake Segregation Center detainees to commemorate their ancestors’ incarceration. Still, they were never engaged in a formal discussion with municipal authorities over the land sale, she says.

“The area has not been very amenable to preserving our history,” she says. The committee struggled fruitlessly “for all of us to work together to move the airport so they could develop their airport without restrictions of being located by a historic site and preserve the historic site and work to develop the local economy. They persisted in this narrative that we wanted to close the airport, which is just not true.”

The airport has long served as a boon to the area’s key agricultural sector.

Following a public hearing that ignored Takei’s group’s offer and a closed meeting to discuss offers, the municipal government chose to accept the Modoc tribe’s modest $17,500 for the land, which local news outlets reported would only cover the city’s legal fees for the transaction.

Takei’s group was effectively left out of discussions, she says, citing the regions demographics as a potential reason for continued opposition to Japanese-American commemorations of their elders’ incarceration. “This area was self proclaimed white man’s country before World War II,” Takei says, explaining possible reasons why her group was barred from discussions.

(Photo: Resistance at Tule Lake)

Tulelake is located in California’s heavily Republican, rural northern end. Nearly 57 percent of the county where Tulelake is located voted for President Donald Trump in the 2016 election.

Tulelake and Modoc Tribe officials did not respond to requests for comment by the time of publication.

The District Court ruling came “without prejudice,” meaning that Takei’s committee can make another bid to block the sale, answering the judge’s remaining questions on their opposition to the transaction. That bid will be the topic of their deliberations this week.

“Of course the stakes on this are enormous” in the pending legal actions, Takei says. For her, the fight is both personal and about preserving a history to inform future generations of Americans.

Takei’s mother’s family was incarcerated at Tule Lake, a squalid facility designed specifically for Japanese Americans deemed to have been “disloyal” in their responses to a loyalty questionnaire from the federal government. Many of the people who responded that they wouldn’t serve in the U.S. military or refused to disavow loyalty to erstwhile Japanese Emperor Hirohito did so in protest to their discriminatory treatment by the U.S. government.

“When people say Japanese Americans didn’t protest their incarceration during World War II, it’s a totally false narrative, but it’s one people have believed for the past 75 years. That’s part of why Tule Lake’s history is so important,” Takei says.

And Tule Lake’s lessons are especially prescient today, amid the Trump administration’s rhetoric and policies on immigrants, she says. “As we see today, what happened in 1942 and the run-up, what happened that led to the incarceration is being repeated again today.”

The battle to remember Tule Lake to the American public comes as the federal government weighs future funding for commemorations of Japanese-American incarceration. A spending bill that funds the government through September included funds for the Japanese American Confinement Sites program, but the Trump administration’s previously proposed 2019 government spending has omitted that funding.

With the October 1st government funding deadline fast approaching, Takei and other Japanese-American community leaders may soon learn whether the administration plans to continue funding to recall a dark time for American immigrants.

Last month, the community observed 30 years since it secured official recognition of the government’s wartime actions. Now it seems the Japanese-American fight for redress—in Tulelake as in Washington—is still very much underway.