Three years ago, Lisa Conti told us about the retired Google honcho who set about ringing the globe with a network of telescopes available to both school kids and astrophysicists. That effort paid a dividend, made public this week, as the Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network contributed to discovering a planet that orbits two suns, the first such planet definitively identified by human astronomers.

This “circumbinary planet,” to use its fancy name, was detected by NASA’s Kepler space telescope near the constellation Cygnus. (Even NASA couldn’t resist drawing attention to another circumbinary planet in pop culture: Tatooine, the planet where Luke Skywalker of the Star Wars mythos grew up.)

Kepler’s mission is to find habitable planets by looking for a dip in a star’s brightness — eclipses, really — as a hint that a planet is transiting. It pays special attention to bodies roughly the size of Earth in a planetary system’s “habitable zone,” i.e. at the right distance from the star to allow liquid water to exist on a planet’s surface. This latest discovery, dubbed Kepler-16b, is predicted by NASA to be “an inhospitable, cold world about the size of Saturn and thought to be made up of about half rock and half gas.” (Dusty and dry Tatooine was habitable, just.)

The two suns of the Kepler-16 system played a game of celestial tag that produced brightness dips as one crossed the path of the other; when a third dip occurred, Kepler’s researchers felt they had a planet on the hook. The team, led by Laurance Doyle of the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence Institute, then examined changes in gravitational pull — fiddly work at 200 lights years away — to determine that this third body had the right mass to be a planet.

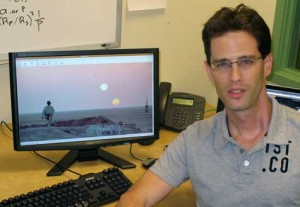

While the space telescope is busy making a first identification, the ground-based telescopes of Las Cumbres, among others, wrestle the sighting down until it’s unambiguous. That’s what happened here, explained University of California, Santa Barbara, astrophysicist Avi Shporer, a member of both the Kepler team and Las Cumbres network.

“I used one of our telescopes, the Faulkes Telescope North [in Hawaii], to observe Kepler-16. The data was used at the beginning of the process of verifying the target is ‘real,’ meaning it is really a planet orbiting a double star system and not something else. You can think of it as observations done for initial screening of false positives.”

“At [Las Cumbres], we are using our telescopes as part of the large effort carried out by U.S. astronomers and others, to follow up and accurately characterize the detections made by Kepler,” Tim Brown, the network’s scientific director, an adjunct professor of physics at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and a member of the Kepler team, explained in a release.

While Faulkes is in Hawaii, the Las Cumbres project has or plans to have telescopes in at least seven sites around the world, including California and Texas in the U.S., Australia, Chile and the Canary Islands.

As Conti wrote in 2008: “The programmable telescopes collect immense amounts of data. Should something occur — a near-planet asteroid, for example — they can be steered to the event within 20 seconds. And with robotic telescopes around the world, an observation that starts in one location can continue elsewhere, increasing the viewing time from eight hours to around the clock. As the nonprofit’s slogan puts it, ‘We will always keep you in the dark.’”

This discovery is one of many that Las Cumbres has assisted on, including an exploding star that made news late last month.That supernova first was picked up by a 48-inch telescope at Palomar Mountain in California.

Wayne Rosing, a retired Google vice president of engineering and one of the brains behind the Java platform, founded Las Cumbres. His plan was not only to help keep the skies under constant surveillance for scientific purposes, but also to provide an outlet for school children to get excited about astronomy. “If we can help another generation — the upcoming generation of young people — appreciate the notion of a scientific way of looking at the world,” he told Conti, “we will have made an important contribution.”

Speaking of contributions, Shporer said Kepler, which was launched in March 2009, probably has its most interesting discoveries ahead of it.

This discovery of Kepler-16b was announced in the journal Science.

Sign up for the free Miller-McCune.com e-newsletter.

“Like” Miller-McCune on Facebook.

Follow Miller-McCune on Twitter.

Add Miller-McCune.com news to your site.