With just a handful of prescriptions to his name, psychiatrist Ernest Bagner III was barely a blip in Medicare’s vast drug program in 2009.

But the next year he began churning them out at a furious rate. Not just the psych drugs expected in his specialty, but expensive pills for asthma and high cholesterol, heartburn and blood clots.

By the end of 2010, Medicare had paid $3.8 million for Bagner’s drugs—one of the highest tallies in the country. His prescriptions cost the program another $2.6 million the following year, records analyzed by ProPublica show.

Bagner, 46, says there’s just one problem with this accounting: The prescriptions aren’t his. “All of that stuff you have is false,” he said.

By his telling, someone stole his identity while he worked at a strip-mall clinic in Hollywood, California, then forged his signature on prescriptions for hundreds of Medicare patients he’d never seen. Whoever did it, he’s been told, likely pilfered those drugs and resold them.

“These people make more money off my name than I do,” said Bagner, who now works as a disability evaluator and says he no longer prescribes medications.

Today, credit card companies routinely scan their records for fraud, flagging or blocking suspicious charges as they happen. Yet Medicare’s massive drug program has a process so convoluted and poorly managed that fraud flourishes, giving rise to elaborate schemes that quickly siphon away millions of dollars.

Frustrated investigators for law enforcement, insurers, and pharmacy chains say they don’t see evidence that Medicare officials are doing much to stop it.

“It’s kind of a black hole,” said Alanna Lavelle, director of investigations for WellPoint Inc., which provides drug coverage to about 1.4 million people in the program, known as Part D.

Lavelle said her team routinely refers doctors and pharmacies to the contractor Medicare hires to pursue fraud. “Oftentimes we never hear back, positive or negative.”

Since it started in 2006, Part D has been lauded for its success in getting needed medications to more than 36 million seniors and disabled enrollees.

But over the past year, ProPublica has detailed how Part D is beset by weak oversight. Medicare doesn’t analyze its prescribing data to root out doctors whose inappropriate drug choices endanger patients. Nor has it flagged those whose unchecked devotion to name-brand drugs, instead of generics, adds billions in needless expense.

For this story, ProPublica again scrutinized Medicare’s data, this time to identify scores of doctors whose prescription patterns bore the hallmarks of fraud. The cost of their prescribing spiked dramatically from one year to the next—in some cases by millions of dollars—as they chose brand-name drugs that scammers can easily resell.

Sometimes the doctors claimed they were unwitting victims of identity theft. In other cases they were paid for writing bogus or inappropriate prescriptions.

A reporter initially contacted Bagner to ask about the high cost of his prescribing, then learned that his flood of prescriptions had already drawn the attention of law enforcement, the fraud units of at least two insurers, and Medicare’s fraud contractor by as early as mid-2010.

All these entities knew that Bagner claimed his identity had been stolen, documents and interviews show. Some of the investigators suspected he was not being wholly truthful about his involvement. Still, Medicare never blocked his national provider ID, which is used to fill prescriptions, Bagner said. The same was true with other physicians ProPublica identified.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which runs Part D, declined to make an official available for comment and would not answer specific questions. Instead, a spokesman sent a brief statement saying the agency “actively works to detect and prevent provider fraud” and refers cases to law enforcement if appropriate.

Law enforcement investigators and insurers say a marked increase in tips, complaints, and cases suggests that Part D fraud is rising, but because pursuit of it is scattershot, gauging the extent is impossible.

Criminals are “coming up with new schemes, and drugs that are being diverted every day,” said Michael Cohen, an investigator with the inspector general of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

Bagner’s case and others like it show how fast a single doctor can be used to run up a staggering tab.

Part D is vulnerable because it requires insurance companies to pay for prescriptions issued by any licensed prescriber and filled by any willing pharmacy within 14 days. Insurers generally must cover even suspicious claims before investigating, an approach called “pay and chase.” By comparison, these same insurers have more time to review questionable medication claims for patients in their non-Medicare plans.

Fraud rings use an ever-evolving variety of schemes to plunder the program.

In one of the most popular, elderly, broke, disgraced, or foreign-trained doctors are recruited for jobs at small clinics. Their provider IDs are used to write thousands of Medicare prescriptions for patients whose identities also may have been bought or stolen. Once dispensed, the drugs are then resold, sometimes with new labels, to pharmacies or drug wholesalers.

In other schemes, investigators say, pharmacies are active participants, billing Medicare multiple times for prescriptions they never fill.

Doctors can readily disavow the prescriptions as forged, investigators say. And because the schemes don’t always involve painkillers, a law enforcement focus, they can escape notice.

Stymied by Medicare’s inaction, the task of pursuing such cases sometimes falls to local agencies such as Los Angeles County’s Health Authority Law Enforcement Task Force.

Sheriff’s Sergeant Steve Opferman, who heads that task force, said he doesn’t understand why Medicare does not make fraud more of a priority. Part D is “icing on the cake” for crooks, he said.

“Why is the government so reluctant to stop this?” he asked.

‘A DEAL WITH THE DEVIL’

In September 2006, federal officials called a meeting in Los Angeles to brief law enforcement on Medicare’s freshly launched prescription drug program.

When it was over, Opferman announced to a colleague: “Let the crime spree begin.”

Sure enough, Opferman said, it did.

From a beat-up office in a county building in downtown Los Angeles, his team now spends about half its time chasing down Part D scams in one of the country’s Medicare fraud hot spots.

Opferman has the pony tail, tattoos, and scruffiness that go with working undercover and an impressive ability to recall the intricacies of dozens of such scams. He said it didn’t take long for local organized crime rings to suss out Part D’s weaknesses.

The scams he works are usually tied to Armenian organized crime rings. They depend, in large part, on a steady supply of doctors who are either oblivious or corrupt enough to look the other way.

“These people aren’t very bright,” Opferman said. “They’ve made a deal with the devil.”

Some doctors get hooked in after answering Craigslist ads seeking “Medical Director for clinic.” One doctor who did so got suspicious, but by the time she backed out, prescriptions already were being billed in her name, one of Opferman’s team members recalled.

In some cases, Opferman and others say, the doctors are paid a flat fee to review a small percentage of patient charts once a week, while dozens, even thousands of prescriptions, are churned out under their names and filled at local pharmacies.

When one doctor’s identification becomes “hot,” the scammers simply find another.

In a locked room deep in the bowels of Opferman’s building, boxes of drugs seized in raids are stacked to the ceiling. Gallon-sized plastic bags of pills. Piles of bottles with labels soaked off with nail polish remover, ready for new ones. Even a baby stroller used to peddle pills in a local park.

The painkillers, including such drugs as Oxycontin and Vicodin, are sold on the street to addicts, Opferman said. Expensive drugs for other conditions are resold back into the supply chain—to other patients, pharmacies, or drug wholesalers.

Among the most popular are drugs such as the antipsychotic Abilify, which costs upward of $750 or more for a 30-day supply, or the heartburn pill Nexium, which runs at least $240.

In some cases, drug wholesalers repackage expired medications, which are ultimately dispensed to unsuspecting patients.

Opferman said Medicare is of scant help to local agencies trying to combat Part D fraud. It can take “months or years,” he said, to get basic information, such as a physician’s prescribing or billing data, from the program.

“It’s like pulling teeth,” he said.

In contrast, Opferman said, Medi-Cal, the state-run insurance program for the poor, is quick to share its data. Medi-Cal can move to restrict a doctor’s ability to prescribe certain drugs if fraud is suspected and, in some cases, it suspends them from the program, state officials said.

Opferman and other investigators say Medicare could stanch much of the fraud by ensuring that doctors and pharmacies are legitimate and by quickly shutting off provider IDs associated with fraud. In many cases, the doctors’ clinics turn out to be little more than rooms with a telephone, while the pharmacies are simply storefront pill mills, they said.

At the very least, WellPoint’s Lavelle suggests, Medicare or its fraud contractor could use Google Earth to see if the pharmacies even exist.

In the years since his first meeting about Part D, Opferman has come up with his own presentation about the program for his fellow fraud investigators. One slide is titled “An Invitation to Steal $$.”

HIS DREAM WENT SOUTH

At the beginning, when an Armenian woman offered to open a clinic for him, Bagner said he could see no down side. She’d set up the site, find the patients, handle the billing. And when the Medicare reimbursements rolled in, he’d get paid.

“My office. I risk no money. I see patients,” Bagner recalled thinking. “Sounds good. Something I dreamed about as a kid.”

At first, all was well, Bagner said. He’d see about 10 patients a day, usually older Armenians and Hispanics, at an office on an overstuffed stretch of Hollywood Boulevard. About three months in, he said, his dream went south. Two investigators—he can’t recall from which agency—showed up with a stack of prescriptions and patient records. They said he’d ordered more than $3 million worth of wheelchairs, neck braces, and drugs since the clinic had opened.

They brought medical records that were copies of his actual files, Bagner said, but with different patient names written in. The prescriptions bore a fake signature that closely resembled his, he said, and they were written to patients he didn’t know.

“I wrote my signature. I showed them,” he said. “They saw the difference.”

The investigators told him he was likely a victim of a scam, Bagner said, and promised to get back to him.

About a month later, the woman who ran the clinic abruptly closed it before he’d ever been paid, Bagner said. He never had a contract, he said, and couldn’t recall her last name. Soon after, an investigator from CVS Caremark began calling.

“He was insinuating I was getting kickbacks for writing expensive drugs,” Bagner said. “I called him back and said those patients were not mine.”

At that point, Bagner said he didn’t know how he could prove he hadn’t been party to the fraud. “Theoretically, hypothetically, I could sign my name a weird way and say, ‘No, it’s not mine,'” he said. “I could give my charts to the Russian mob.”

Bagner blames horrible business sense for falling prey to the scam. He rose from a childhood in gritty East Oakland to attend the University of California-Los Angeles for his undergraduate degree and medical school. Nowhere in his training, he said, did anyone teach him how to run a business. He said he had previously lost $30,000 that he loaned to another clinic.

“I’ve never talked about this because it’s embarrassing,” he said. “I know medicine. I know psychology. When it comes to business, I’m like a retarded person.”

Bagner said he doesn’t even know what Part D is or how much drugs cost. “If you told me you’d give me a million dollars right now if I could tell you how much a month of Prozac costs under that program,” he said, “I have no idea what Part A or B or C or G is.” (There is no Part G.)

Over the course of several interviews, Bagner’s story changed somewhat. He initially insisted that no one had asked about his prescribing other than the CVS staffer and the investigators who visited him. But later he recalled that he had also been contacted by at least one other insurer and by a detective with Opferman’s task force.

Opferman said he came across Bagner in January 2011, when a pharmacist called about suspicious prescriptions someone had dropped off. When a driver brought patients to pick up the drugs, officers met them. They found that the “patients” were not the people named on the prescriptions, and the driver had been paid by a woman working at a strip-mall pill mill, according to a search warrant affidavit.

A follow-up search turned up a stack of prescriptions supposedly signed by Bagner in the woman’s purse, Opferman said. The case is still under investigation, but at this point Bagner is considered a victim, Opferman said.

Bagner plays in poker tournaments and fancies himself good at reading his opponents. He said he still doesn’t know why the scammer chose him.

“I’m grateful and amazed that I haven’t gotten in trouble with this,” he said.

HOW MOST CASES DIE

When criminals plunder Part D, justice is rarely swift. Investigators from so many agencies are involved that chasing down fraud often seems like a relay race in which someone fumbles the baton—or stops well short of the finish line.

Unlike other parts of Medicare, Part D is entirely run by private insurance companies, which are paid by the government to process the bills. According to their contracts, the insurers are supposed to look out for fraud.

Cases typically begin when insurers notice spikes in a doctor’s prescribing or are tipped off by a patient, pharmacy, or disgruntled employee.

If insurers suspect fraud, Medicare encourages—but does not require—them to notify its Part D fraud contractor, a private firm hired to review complaints and recommend cases for investigation. The insurers, however, are not allowed to block a suspect doctor’s prescriptions.

Moreover, insurers can see only the fraction of a doctor’s prescribing record that involves their members—they have no insight as to whether the pattern extends to other companies. Only Medicare and its fraud contractor can see that information.

When tips from insurers reach the contractor, they join those coming in from patients and others. But the contractor can’t directly access patient medical charts to assess whether the patient actually saw the doctor or had a condition that warranted the medication. It must go back to the insurers, which then request the records from doctors or pharmacies.

Most cases die at this level. Between April 2010 and March 2011, the contractor started 1,800 Part D reviews, but forwarded only about 220 for further investigation, according to a report released earlier this year (PDF). Nearly all of those cases went to the Health and Human Services inspector general, which has a team of special agents that investigate fraud.

There, the Part D cases compete for attention with an array of other Medicare frauds, from kickbacks for lab referrals to unnecessary spinal surgeries. Of the 7,800 entities investigated for health care fraud—not just Part D—by the inspector general in 2010, just 14 percent were referred for prosecution.

The rest were dropped, “mainly due to lack of resources or insufficient evidence,” a 2012 report from the Government Accountability Office (PDF) found.

Even when the inspector general believes cases merit criminal charges, prosecutors don’t always pursue them. Each U.S. attorney’s office around the country sets its own priorities, which may not include health-care fraud.

At every stage, Medicare continues to allow prescriptions written by suspect doctors to be paid for by Part D. It only blocks them after a doctor is formally excluded from Medicare by the inspector general, an action that can take months, even after a conviction and sentencing.

In interviews, investigators at various levels deflected blame to others or cited a lack of funding to explain why so few cases are pursued.

Regardless of who is at fault, inattention to fraud has a steep price, they acknowledged.

“It costs the nation, beneficiaries, and plan sponsors hundreds of millions of dollars—if not billions—each year,” said Jo-Ellen Abou Nader, who runs the waste, fraud, and abuse program at Express Scripts, a pharmacy benefit manager that runs its own Part D insurance plans and manages those of 50 others.

She said Express Scripts prowls its claims for fraud on a daily basis using dozens of indicators that include a physician’s prescribing history and drug mix.

But not all insurers do this, and some have been faulted (PDF) for failing to alert Medicare to suspected fraud.

Abou Nader said every entity in the chain lacks the resources to get the job done. “You try to get as much through as you can,” she said.

There are ways to change the system.

Congress could, at Medicare’s urging, change laws to give insurers more time to weed out fraud before paying claims. It could also give them more discretion to suspend doctors and pharmacies.

Currently, insurers must pay Part D pharmacy claims electronically within 14 days. Private plans have up to 30 days. Congress added the quicker turnaround in 2008 at the urging of pharmacies, which complained of payment delays. The change took effect in 2010.

“They’re public policies that actually promote fraud,” said Mark Merritt, CEO of the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, which represents pharmacy benefit managers. “There’s zero upside for consumers.”

‘THE CASE REALLY BLEW UP’

In early 2011, federal investigators wiretapped the phones of Babubhai Patel, the owner of several Detroit-area pharmacies. They suspected him of improperly dispensing narcotics and other controlled drugs.

The investigators learned that Patel wasn’t just peddling painkillers.

The 51-year-old pharmacist had a stable of doctors willing to write Part D prescriptions for any drug he wanted, any time he wanted. In return, the doctors got cash, a flock of new patients, and, in at least one case, a down payment for an office building, federal prosecutors claim.

“The case really blew up,” said John Neal, an assistant U.S. attorney who prosecutes health care fraud in Detroit.

Over several months, investigators unraveled one of the largest prescription drug scams ever prosecuted—and much of the fraud came at Medicare’s expense.

According to court records, Patel’s pharmacies billed Medicare and other insurers for the doctors’ prescriptions, then got paid a second time when the drugs were resold. Some patients who allowed Patel to process phony prescriptions in their names received painkillers as kickbacks, as did people who recruited patients for the scheme.

In all, Patel’s 26 pharmacies billed Medicare for more than $37 million from January 2006 to August 2011. They billed another $23.1 million to Michigan’s Medicaid program, court records show.

Unlike other jurisdictions, the U.S. attorney’s office in Detroit has made Part D fraud—and the doctors who play a role in it—a priority. The office ranks among the country’s leaders in prosecuting Medicare fraud.

“I think as a general matter, that Part D fraud is a significant problem here,” said Neal. “And billing for medically unnecessary and/or never dispensed Part D drugs is a problem here.”

So far, 39 people have been indicted in the Patel scheme, including eight doctors, a podiatrist, and a psychologist. Of those, 31 have pleaded guilty or have been convicted by a jury, and two more are scheduled to enter guilty pleas. Two doctors are set to go on trial early 2014. A jury found Patel guilty in 2012; he is serving a 17-year prison sentence.

Among those who pleaded guilty is psychiatrist Mark Greenbain, now 71, to whom Patel allegedly paid $500 every week for prescribing expensive antipsychotics. Witnesses said the two would sit together in Greenbain’s house. “Patel would direct Greenbain what medications to write, and Greenbain would demand cash in exchange,” prosecutors wrote in their sentencing memo.

Greenbain’s prescriptions cost Medicare $2.3 million in 2011, ProPublica’s analysis of Part D data shows. He was recently sentenced to four years in prison. He still has a clear license, according to Michigan’s medical board website.

A jury found another medical professional, podiatrist Anmy Tran, guilty of steering patients and prescriptions to a Patel-owned pharmacy in her building. Tran, 42, was caught on wiretap discussing her prescriptions with Patel, who said: “Your end is tremendously OK, excellent,” court records show.

When Tran was arrested in 2011, she told an investigator for the HHS inspector general that in return for referring patients, Patel helped cover the down payment on her office building, paid her tax bill, and provided support to the Vietnamese community, according to court testimony.

Years before she caught the attention of prosecutors, Tran’s prescribing stood out starkly from that of her peers, data obtained by ProPublica show. In 2011, her Part D spending was higher than any other podiatrist’s in the country, costing Medicare $756,000.

Neither Medicare nor state regulators have taken any action against Tran, who still has the ability to write prescriptions.

Tran’s lawyer is seeking to overturn her conviction, calling it a “miscarriage of justice.” All her prescriptions were written for legitimate medical reasons, and she didn’t know Patel was corrupt, attorney David Steingold wrote in a motion to the U.S. District Court in Detroit.

Neal said it’s important to pursue doctors involved in these schemes to alert the community that this kind of behavior has consequences.

“Patel’s empire could not have existed or certainly sustained itself for as long as it did without the active cooperation of doctors,” he said.

HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

A misdirected fanny pack alerted Dr. Carmen Ortiz-Butcher that something was wrong. She’d asked a staffer to mail it to her brother a couple months ago, but it never arrived. Instead, he got a bunch of prescriptions ostensibly signed by Ortiz-Butcher, said her attorney, Robert Mayer.

Ortiz-Butcher, a Florida kidney specialist, suspended one of her employees and alerted authorities. But it wasn’t until ProPublica contacted Ortiz-Butcher, 59, for this story that she learned just how extensive the fraud was, Mayer said.

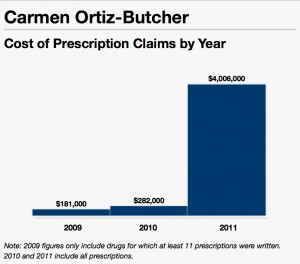

According to Medicare data, the scam appears to have started two years earlier. In 2011, the number of prescriptions Ortiz-Butcher wrote more than quadrupled from the previous year, to 16,000. And the cost of her drugs to Medicare spiked from $282,000 to $4 million.

The cases of Ortiz-Butcher and other doctors identified by ProPublica show how easy it is to spot potential fraud in Medicare’s own data.

“At no time had anyone contacted her about the frankly amazing increase in her prescriptions in the last two years,” Mayer said.

In some instances, when ProPublica asked doctors about the huge spikes in their prescribing, they recounted multiple situations in which someone appeared to be using their identity for suspicious activity.

It isn’t hard to spot Miami physician Aurelio Ortiz in Medicare’s Part D prescribing data. He’s the one whose prescription tab ballooned from $2.1 million in 2010 to $8.7 million the next year—the fourth-most in the country.

The 70-year-old doctor’s most-prescribed drugs read like a shopping list of the pills that are most valued in scams.

When ProPublica called him up, Ortiz (no relation to Ortiz-Butcher) couldn’t recall whether the prescriptions were his: “Right off the bat, I couldn’t say yes I did or I did not.”

He later said he’d been aware that some bogus prescriptions had been written using his name. At one clinic, “I found two or three prescriptions forged,” he said. “I resigned from the clinic, and I didn’t go there anymore.”

At another clinic, he said, “They had a gentleman who said he was a physician assistant … but this guy also forged my signature for medications.”

“If something has been going on,” Ortiz said, “no one has called me like you to tell me that there’s over-prescription of medications.”

Often doctors caught up in such scams have records of disciplinary action or financial difficulty. In 2006, Ortiz was placed on probation for three years by the Texas medical board, and he was subsequently disciplined by the Florida board, for falsely claiming to have examined a patient. Ortiz said he has resolved these issues and has had no problems since.

Another doctor whose prescriptions spiked one year, then virtually disappeared the next, maintained that she had fallen victim to more than one fraud.

Anesthesiologist Ruth Fontaine said she was “bankrupt and bereft” after her holistic medicine practice failed. Then a colleague told her about an Armenian man who ran an outpatient clinic near Los Angeles, she said.

It was the first of three clinics Fontaine, 64, would work at during the next three years, each entangling her in suspicious activity or fraud.

The first closed abruptly in 2007 after the owner declared he was out of money then disappeared, Fontaine said. The next morning, she found the lock sawed out of the clinic’s front door, she said.

Undeterred, Fontaine joined a second clinic. There she was visited by fraud investigators who asked about her prescriptions for motorized wheelchairs, Fontaine said. Half of them, she said, were not for her patients. Then pharmacists began calling about prescriptions for Oxycontin she hadn’t written, she said.

When Fontaine refused to write any more prescriptions for pain pills, the second office also suddenly closed, she said.

Nonetheless, Fontaine joined a third in 2010. This one was open for less than a month. Fontaine said she wasn’t hired to see patients, but rather to oversee the work of a physician assistant, who could prescribe under her name. But she said she never met the assistant and later discovered prescriptions were being attributed to her before she even learned the clinic’s address.

“I started asking too many questions,” Fontaine said. And then one day, the clinic’s phone was turned off.

The FBI later visited Fontaine and said she’d likely been the victim of identity theft, she said. The FBI declined to verify her claim.

Medicare data show her short stint at the final clinic in 2010 resulted in prescriptions worth more than $520,000.

This post originally appeared on ProPublica, a Pacific Standard partner site.