There has never been a drug-free society, the writer Maia Szalavitz reminds us in her cover story. And for the past century, our policymakers have responded to the challenge of managing public drug use in a manner that is, alas, riddled with contradictions: We have enforced strict bans on some intoxicants (cocaine, ecstasy, marijuana) and allowed the legal sale of other addictive substances (nicotine, alcohol, caffeine). Some legal substances are quite dangerous to public health; some illegal ones appear safe by comparison. Along the way, the United States has spent more than a trillion dollars enforcing anti-drug laws, and has imprisoned millions of people.

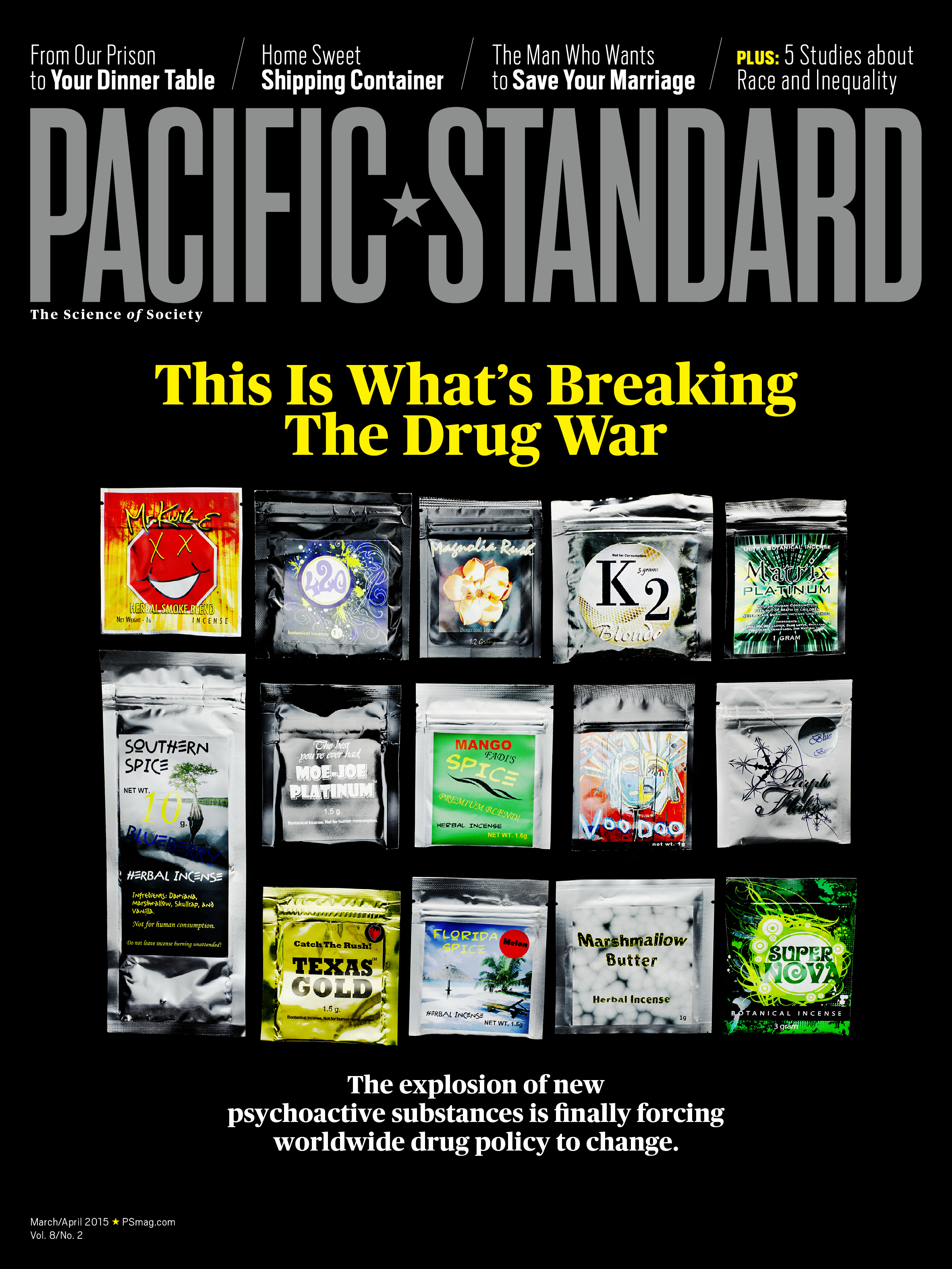

About a decade ago, however, something important started to happen. In line with our increasingly open-access, on-demand, DIY culture, people began to manufacture new psychoactive substances—a wild proliferation of chemically distinct products crafted to mimic the effects of those we more easily recognize, like marijuana or ecstasy. Want your own? With a bit of money and research, you can email a laboratory overseas that will tweak a chemical formula and mail you a new thrill.

These new drugs are coming out at such a clip that governments can’t keep up with policing or banning them. Many are freely available in stores, though they can be more dangerous than the illegal drugs they copy. In the United States, 11 percent of high school seniors have tried variants of synthetic marijuana—a poorly understood class of products that are far more risky than marijuana itself.

This onslaught of new substances has begun to force some of the world’s drug control agencies to rethink their policies—perhaps for the better. Historically, our war on drugs has been inseparable from issues of race and inequality. A look back at the early 20th century shows that each time a drug was banned, it was in the midst of a racial panic that associated the substance with a demonized minority. The effects of drug enforcement have long been racially disproportionate, as well. “Although blacks and whites use and deal drugs at comparable rates, African-American men are sent to prison for drug crimes at a rate that is ten times higher, according to the NAACP,” Szalavitz writes at the website Substance.

This issue’s Five Studies column adds context to this statistic. In “Inequality in Black and White,” Kathleen Geier points to research showing that racial sentencing disparities—the average white defendant gets 14 months for drug possession, while the average black defendant gets 17 months—can have outsize consequences, as incarceration spreads like a contagion within communities.

For a number of reasons, the blitzkrieg of new psychoactive substances has begun to push drug enforcement agencies away from policies that prioritize incarceration and toward the reduction of harm. The transformation started in, of all places, the quiet nation of New Zealand, where Szalavitz takes you, in her splendidly reported story.

MORE IN THIS ISSUE

At the intersection of social justice and public interest.

With one out of every 137 Americans behind bars, you could almost think of Incarcerated America as a separate nation within our own—one whose population is larger than that of Slovenia. In this issue, we examine relations between the two Americas on a couple of fronts, both of which strain basic ideas of justice and democracy. In “Raised in Captivity” we look at trade policy between America and the low-wage nation of prison labor, which manufactures a surprising number of the goods we enjoy (attention Whole Foods shoppers); and in “The Outcast at the Gate” we look at the troubled border between prison and life on the outside for a class of people few of us want to think about: child molesters who have “paid their debt to society.”

Americans have a long history of idealizing the nuclear family as a bulwark of virtue and stability—“a moral yardstick with which to measure the public realm,” writes the sociologist Richard Sennett. But the yardstick keeps changing, and as the historian Stephanie Coontz writes, the “turn towards home” in national discourse often comes at a time when public supports are being allowed to collapse. In this issue, Jessica Weisberg writes about the hugely popular self-help guru Harville Hendrix’s quest to promote marriage among Americans of all economic classes, recognizing that the wealth gap between the married and the unmarried has widened threefold since the early 1960s. And in “Aunt Mommy” Rachel Rabkin Peachman examines the mind-bending and morally tricky family arrangements that are resulting from the rise of assisted reproductive technology.

For more from Pacific Standard on the science of society, and to support our work, sign up for our email newsletter and subscribe to our bimonthly magazine, where this piece originally appeared. Digital editions are available in the App Store (iPad) and on Zinio (Android, iPad, PC/MAC, iPhone, and Win8), Amazon, and Google Play (Android).