The first murder I can remember hearing about was committed with a baseball bat. I was sitting in the living room of the mission house in Fort Yukon, Alaska, having a tea party with my dolls, when the words “murdered,” “decapitated,” “baseball bat,” and “drunk” floated past my ears, drifting over from a nearby conversation. I never learned more. Many years later, I asked my parents about the specifics, but they couldn’t recall. I knew from then on, though, that the world was more than what I saw in front of me. But knowing that something like murder exists isn’t the same as understanding what it really means. And until my senior year of high school in Fairbanks, a city 140 air miles southwest of Fort Yukon, murder was something that involved only strangers.

For five years when I was a child, my family lived in Fort Yukon, a Gwich’in Athabascan community where many people lived a subsistence lifestyle, hunting and fishing, trapping and gathering their food. My father was priest-in-charge of St. Stephen’s, the Episcopal church established there in the late 19th century. I loved growing up in Fort Yukon; I felt free and alive as a kid, close to something powerful in the river and the light and the trees. But, despite the peaceful simplicity of a schedule dictated by the seasons, it was not always an easy place to live. Violence and tragedy were an intimate part of life.

Some of my friends from high school think that I’m obsessed with the murder. But I don’t want the silence to be the story.

Back then, a lot of the area’s strife came through the mission house. The phone would ring in the night and my dad would leave, or someone would bang on the door, shouting, and my parents would let him in, or a grieving mother would sit on our couch for days at a time, numbly accepting food, crying under a blanket. When there was death, people talked openly and worked together to do what had to be done: The young men dug the graves, lighting fires to thaw the ground in the winter; the grandpas built the coffins; the grandmas sewed and beaded; the women cooked. Death was not sanitized or ignored; it was understood.

When I was six, my family moved to Fairbanks. At first, I loved my new surroundings. But after the glamour of the well-lit grocery stores, the McDonald’s, and the local swimming pool wore off, I just wanted to go home—or at least, what I still considered home—to Fort Yukon. I didn’t feel safe in Fairbanks. If you lost something on the street, it was unlikely that you’d ever find it again. There were places we were told to avoid on our walks to school, like the bike path along the river. But still, I remained a mostly oblivious, mostly happy child. It wasn’t until a murder in Fairbanks in 1989 that I really felt the stark differences between the two places where I’d grown up: One of my friends brutally murdered another one of my friends, and the ensuing silence in Fairbanks around the murder compounded the shock of the crime itself.

Only now, decades later, am I beginning to understand why people in Fairbanks went quiet, so unlike the people in Fort Yukon. Some of my friends from high school think that I’m obsessed with the murder, that I need to let it go, to move on. They’ve made their peace with the past, they say, and I should too. But I don’t want the silence to be the story.

On January 4th, 1989, 16-year-old Byran Perotti kidnapped Johnny Jackson, 18, at gunpoint from the parking lot of Los Amigos, the Mexican restaurant where Johnny worked, and drove on Lathrop Street to the Tanana River, about three miles away. According to court documents, Byran held Johnny hostage for an hour and a half in his truck before walking him across the ice to an island 100 yards away and shooting him twice in the head. Byran then stripped Johnny’s body, poured gasoline on it, and attempted to burn the corpse. When that failed, he hid Johnny’s remains under an embankment, surrounded by snow and frozen dirt.

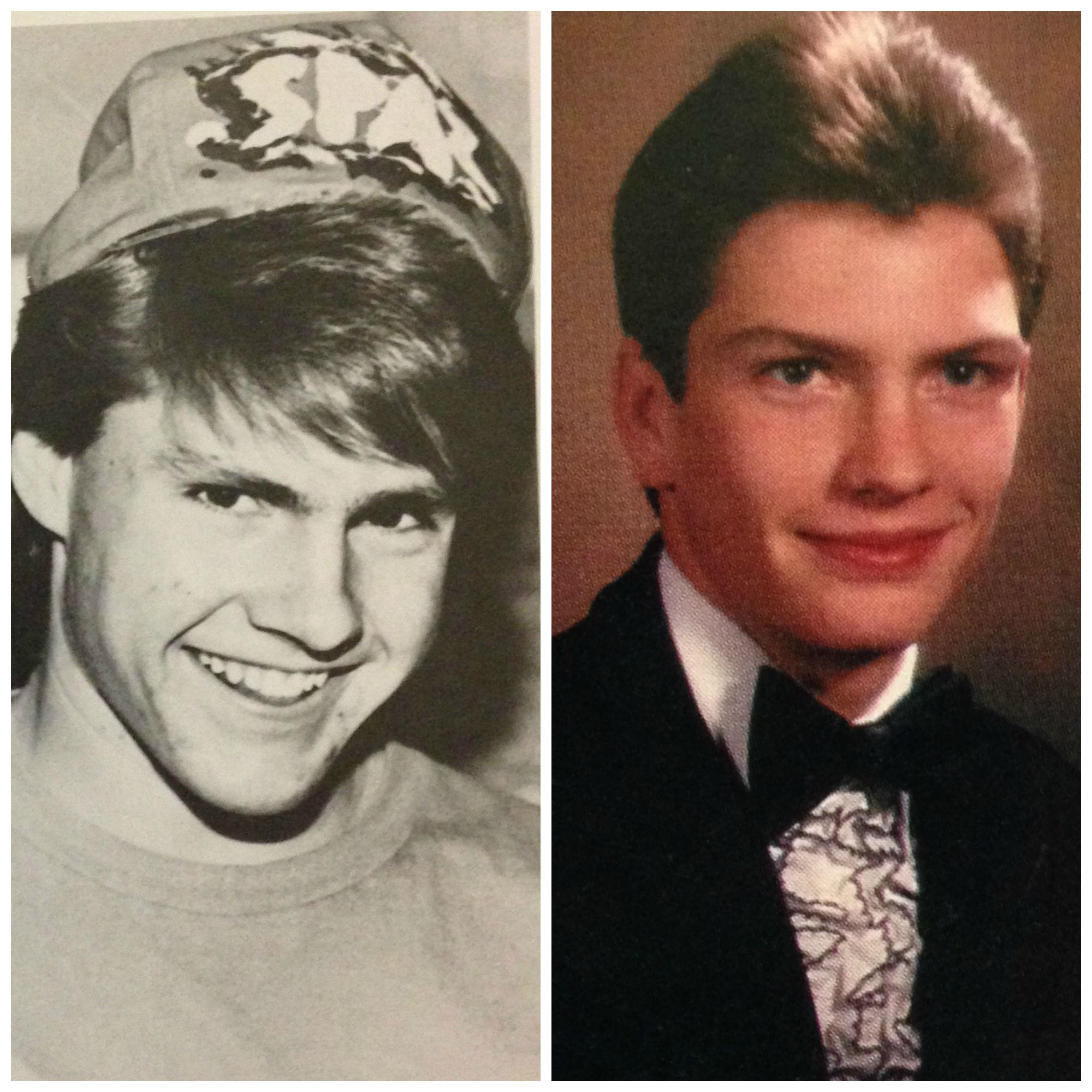

Byran and I knew each other from church, St. Matthew’s, the historic Episcopal church on the Chena River, which runs through downtown Fairbanks. He was a year younger than I was, but we would hang out after the service, prowling aimlessly around the building. We once shared a meaningless kiss in a dark bathroom, as teenagers sometimes do. We didn’t interact much at school because we were in different grades and social circles, but settled for the nod and smile when we passed each other in the hallways.

Byran liked attention and tried constantly to generate it. Once, he procured an old couch, which he somehow stowed at school. He would lounge on this couch during school assemblies, directly in front of the bleachers where his classmates sat, just for a laugh. Byran and his friends would catcall girls in the hallways, flipping up their skirts and snapping their bras. (This was back when such actions were generally dismissed with an amused “boys will be boys” eye roll.)

At some point during his sophomore year, Byran acquired a girlfriend. He went to extremes, always: jockeying for the title of class clown, starving himself to cut weight for wrestling, public displays of affection with his girlfriend—not just kissing and hand-holding, but flowers and stuffed animals at school. He kept taking his parents’ car after they were asleep to go to her house. His parents didn’t know what to do; he wouldn’t listen to them. Finally, his father threatened to call the police if Byran took the car again. Byran did it again, and his father called the police.

My mother was a good friend of Byran’s parents, and sometimes our families would get together for meals. She told me about their struggles with Byran. No one at school seemed to know about Byran getting into trouble at home, and I didn’t think much of it. I was distracted by my own life, focused on my schoolwork and getting into college.

I was working out at a local gym in early January when I heard on the radio that Johnny was missing. I was on the bench press. I put the bar back on the rack and lay there for a minute, thinking, praying. It wasn’t that unusual for people to go missing in Fairbanks; we’d gotten somewhat used to that, unfortunately, over the years. It usually meant they were dead, though, and that they’d been murdered, rather than an accidental death like drowning, which was more likely to happen in a place like Fort Yukon, where people regularly traveled on the nearby rivers.

Johnny was goofy and charming, with a smallish build but big feet, like he still had a lot of growing to do. He wore black-and-white checkered Vans and talked to everyone, ignoring the strange high school etiquette that discourages interaction between social groups. Johnny and I hadn’t quite dated, but we’d hung out over the years. We held hands under a blanket at a party once, went to see Planes, Trains, and Automobiles when it was in theaters, and stayed friends after he graduated. He worked in the kitchen at Los Amigos, and liked to roller skate, I remember.

In the spring of 1988, nine months prior to the murder, Byran’s girlfriend was overheard by a school official telling a friend that Johnny had raped her when they went out on a date a month or so earlier, before she had started seeing Byran. The school official reported it, but upon being questioned by the police, Byran’s girlfriend declined to press charges. Johnny, according to court documents, “adamantly denied any assaultive conduct.” Citing a lack of evidence, the police declined to go forward with the case.

The accusation was generally understood not to be true. I didn’t think it was true. It was like a big open secret, an opinion we all shared and didn’t feel the need to discuss. Even Byran doubted the claim: He told his family that he wasn’t exactly sure what had happened, because his girlfriend refused to give him any details. But he became consumed with the idea of defending her honor, taking the alleged assault as a personal affront and twisting it into a very public vendetta against Johnny. In a letter to his girlfriend dated May 11th, 1988, Byran wrote:

This may sound egotistical, and possessive, but he took something that was mine—it was and is a part of me, it was, is, like he did it to me, even though I don’t know what happened or exactly how much he hurt you. But he stole something that is very precious to me, something that cannot be returned. I want it back, and by doing what I’m going to do, I will gain something that is equally precious to him.

The suggestion here is that that Johnny and Byran’s girlfriend had sex. Perhaps she regretted it and called it rape, or perhaps Byran was just jealous that anything might have happened at all.

When Johnny’s disappearance was broadcast on the radio, I didn’t immediately think of Byran, though I should have. Byran had been stalking Johnny for months, broadcasting his intent to kill him. It’s strange, but somehow, we ignored the threats. Byran talked a big game, but we all, everyone at school, had assumed that the truth—the reality that Johnny was innocent of the crime he had been accused of—would save him from Byran’s anger.

Johnny tried to brush off the menacing remarks, but Byran was hard to ignore.

Byran threatened Johnny to his face, following him around town, sometimes waiting outside Los Amigos. He said repeatedly to Johnny’s friends and his own friends that Johnny deserved to die. He glared at me when I told him I didn’t think Johnny was capable of hurting anyone, that I’d gone out with him too, that he was harmless, and kind. “Fuck that, I don’t care,” Byran said as he walked away.

It seems crazy now that we didn’t try to do more to help, that we didn’t heed the warning signs. I think it was just impossible to imagine that Byran would ever really do anything more than talk. He was just looking for attention, we thought.

A childhood friend who works in law enforcement in Fairbanks says that the answer, now, is simple: “He was homicidal, and needed someone to kill.” That is to say, if it wasn’t Johnny, it would have been someone else. A 2006 study in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine notes that “attempts to develop models that predict violence have in part been unsuccessful from the fact the ideation is common.” Byran said later that he told everyone he was going to do it, that we should have taken him seriously. It’s difficult to know when teenagers are just fantasizing about killing someone and when they actually plan on doing it.

There were rumors that Byran’s girlfriend recanted and told him that Johnny hadn’t raped her, but it was too late. Even if Johnny wasn’t guilty of assault, in Byran’s eyes he may have had sex with her, and that was just as bad an offense. He told me later, “I didn’t kill him because he raped –––. I killed him because he wouldn’t go away.”

In January, the sun lingers briefly on the horizon at mid-day in Fairbanks, sleepily bathing the city in dim light for a couple of hours before it slips away again. Byran was arrested on a Sunday, in the late afternoon, after dark. That morning, he and I had served together at the altar at St. Matthew’s. One of us, I don’t remember who, was the crucifer, bearing the cross. The other was an acolyte. We’d goofed around as usual, trying to make each other laugh during the service. His father called our house a few hours later. My mother answered the phone, listened, spoke briefly, hung up, and turned to me, where I was drying dishes at the kitchen sink: “Byran’s been arrested for Johnny Jackson’s murder.”

My mother went to sit with Byran’s family at their house. I sat in my room, alone. I pressed my hand, and then my cheek, to an exterior wall; it was cold, -60 outside. I called Byran’s best friend to tell him, not yet knowing he had been involved in the sting operation that led to Byran’s arrest. The friend had arranged, my mother told me later that night, to have Byran meet him at his father’s car dealership, where the police were waiting, after they’d already listened in on a conversation during which Byran described the murder in detail, saying that he’d take this friend out to where Johnny’s body was buried in the coming summer, that they’d have a party.

“By doing what I’m going to do, I will gain something that is equally precious to him.”

At school the morning after the arrest, the hallways were buzzing, partly with shock, but also with the thrill of intrigue and scandal. There was a competition as to who knew Byran and Johnny best, who was closest to the whole situation, who deserved to be the most upset. I can still hear the chillingly matter-of-fact tone with which I delivered the news to a teacher who hadn’t heard: “Byran Perotti killed Johnny Jackson,” I said blankly. She gasped. I continued: “He shot him twice in the head and tried to burn the body.” Her hands went to her face. Her eyes went to the desk in her classroom where Johnny used to sit.

Byran later told me about the arrest, in one of our many phone calls in the months immediately after he killed Johnny. He sounded excited as he described how he’d walked in to the darkened dealership office, how several police officers had stood up from where they’d been crouching behind desks, how they’d pointed their guns at him, shouting “Freeze!” He was sure he never would have been caught if he hadn’t talked so openly to his friend, nor would they have found Johnny’s body had he refused to cooperate.

Byran took great personal satisfaction in the killing; he didn’t want to make Johnny’s death look like a suicide. Byran wanted the murder to be known, and told more than a few people about it in the days afterward. This psychological component was much of the reason he was tried as an adult and why his sentence of 99 years was upheld.

The Byran I knew, the Byran with the easy, twinkly grin, was as dead as the boy he shot. That was almost harder to believe than Johnny’s death, because in the aftermath of the murder, Byran was still alive. He was on the other side of the glass; he was next to me in the visiting room at the jail; he was there, in letters and phone calls.

I can’t completely explain why I continued to have contact with Byran, why I didn’t withdraw and protect myself. I didn’t want to abandon him. Despite what he’d done, I still wanted to see him as someone who deserved, and needed, love.

But then, after Johnny’s funeral, no one talked about the murder, or Byran, or even Johnny. Parents, friends, priests, teachers—nobody seemed to know what to say. The silence grew, becoming as deep and cold as the chill outside. The shock was too much, it seemed; the center, if there was one, could not hold, and Fairbanks just moved on from the whole mess like it never happened. The days lengthened, and as winter became spring the only person I talked to about Byran was Byran himself. I wrote to him at the correctional center in Fairbanks where he was being held; he wrote back and started calling the house as soon as he was allowed access to a phone. He seemed lonely and confused and terrified.

I tried to hold on, but after a few months, I couldn’t anymore. I stopped answering his letters. After I graduated from high school that spring, my parents and sister made plans to move to North Dakota, because my father got a new job. I packed up my childhood in a few cardboard boxes.

I was 18 the last time I spoke with him, sitting on the front steps of my parents’ new house in Fargo, a day or two before my father dropped me off for college on the East Coast. I left Alaska and Byran and Johnny and the murder and everything else behind me, or so I thought.

When I went to college, I didn’t talk about the murder. I didn’t want it to be a part of the new life I was making for myself. And because my parents had left Alaska, too, there was no home for me to go back to, which made it easy to pretend that the murder had never taken place. The silence grew stronger over time.

Five years later, in 1994, while sitting in a Starbucks, I happened upon an issue of USA Today. Unconsciously, I looked at the paper’s state-by-state news briefs. My eyes scanned Alaska first, and the text hit me like a brick: “Two drunk escaped murderers surrendered after finding themselves boxed by road blocks, sharpshooters, and snow-covered Mount Marathon … Byran Perotti, serving 99 years … escaped Tuesday from Spring Creek prison.” He and another inmate had cut through a fence after learning that a section of the alarm system was out of service. I knew this was actually his second attempt. The first time, when Byran was in jail awaiting sentencing, he’d overpowered a guard, grabbed his gun, and threatened him with it. The trouble with that attempt: The gun wasn’t loaded. Clearly, Byran wasn’t only dangerous; he was desperate too. I called my parents in tears, not knowing that by the time the newspaper went to print, he had already been found.

I felt safe after I left Alaska because Byran was locked away—not because I ever thought he would hurt me, but because I didn’t have to think about him. I had trouble understanding, even after he murdered Johnny, how disturbed Byran was. Court records note that Byran told a friend at the time of the murder, “When I shot him and I saw the look on his face I’ve never been so happy in my life, but at the same time I was sick to my stomach.” I held on to that last part at first, Byran feeling sick to his stomach, the part of him that I wanted to believe was the real Byran. Maybe he was not lost completely, not yet anyway. I didn’t want to acknowledge what it meant that he might be able to feel both of those things at once.

It wasn’t until I was forced to again think about the murder, after I saw Byran’s name in that USA Today, that I began to understand why I had run away, and how different the response to tragedy had been in Fairbanks than it was in Fort Yukon. Fairbanks was a gold rush town that, in this case, seemed to be governed by its frontier, everyone-for-himself attitude. It didn’t have the tribal connections, the sense of community you find in Alaska’s villages.

I think I’d always known that leaving Alaska would leave a trail of unanswered questions. I also knew I would one day have to at least try to sort them out. I didn’t, though, until I couldn’t ignore the silence anymore—until those questions started to crowd out other thoughts from my head.

Johnny’s mother embraced Byran’s mother in the courtroom, saying, “Today, we’ve both lost sons.”

Or maybe the opposite is true: Maybe I was waiting for things in my life to get in order before trying to make sense of what happened in Fairbanks. I went to graduate school, I got married, I had children, I started teaching. Maybe the time was finally right.

I had always planned to go back, but after moving to Maine for my husband’s job, 16 years passed before I saw Alaska again. I’ve surrounded myself with pieces of home: split willow root baskets woven by the village grandma who cared for me when I was a baby; a wall-size map of Alaska in our living room; a near-nightly check for the Big Dipper, the constellation on the Alaska state flag.

In starting to write about Alaska, and the murder, I’ve been able to go home in other ways. I’ve reached out to people I had known, members of St. Matthew’s in particular. I asked about Byran’s parents—they still attend services there—and was discouraged from getting in touch with them. But I was given Byran’s address at the state-run correctional facility in Seward, Alaska, the prison he’d escaped from in 1994.

I didn’t reach out to him right away. One night last spring, though, after an intense period of writing and thinking about the winter of 1989 and the way I left home, I dreamt vividly that I was hugging Byran, holding him. I woke up feeling gutted, totally empty, and crying, but also knowing exactly what I had to do. I described the dream in a short note to him the next day, not saying much else.

He wrote back immediately: “Shall we pick up where we left off?”

I wish I could say that Byran’s letters make sense to me, that there lay in those words an explanation of what happened, remorse for what he’d done. But what those letters do provide, it seems, is a way for him to be heard by the administrators where he’s being held. His letters come sliced open and taped shut, with a “√” somewhere on the envelope to show that it’s been read. Byran fills his letters with commentary about bureaucratic nonsense and processes, compliments about certain administrators, complaints about others (never by name).

I give him sketches from my life, the view from my office window, the list of things I’ve done on a given day, things I expect will happen in the coming weeks. At first, we returned again to January 1989, and Johnny, but it quickly became apparent to me that I was never going to be able to understand the depths of his mental illness, or what it truly means to be criminally insane. Byran was tried as an adult at 16 because it was determined that his chances of rehabilitation by age 20 were “slim.” Knowing what I know now, based on his letters to me, I have to agree that rehabilitation, whatever that means, seems unlikely by any age.

I nudged the conversation in other directions, away from Johnny, away from the murder. Byran didn’t try to bring it back around.

Instead, we talk now about our daily lives. “You’d be surprised to know,” he wrote recently, “how busy it’s possible to be in here.” He has beautiful handwriting. He talks often about poetry; he wants me to remember that he was smart, that he still is. He almost always writes back right away.

My letters take longer. I search for words, wary about telling him too much, not wanting to put myself, or my family, at risk, even though I know his release date isn’t until 2065. There is no parole eligibility listed in his records. People around me, my husband, those friends from Alaska who think I’m obsessed, expressed concern at first. But, I explain to them, I still think Byran is worthy of love.

Johnny and I weren’t close, but we would certainly be Facebook friends now, had he lived. He was the kind of guy who would have written on everyone’s walls on their birthdays. He would have been a funny, loving dad, I imagine.

Byran didn’t just kill Johnny; he silenced all of us too. He made it hard to have faith in people. The ensuing hush around the murder reinforced the feeling that the world was not a safe place: If the grown-ups didn’t know how to respond, how were we supposed to? I’ve talked about it with my own mother and father and other people who were parental figures at the time—church friends, former teachers. They all just shake their heads and say simply, “No one knew what to do.” I don’t blame them. The shock was deep.

Talking about it, asking questions, trying to tell the story—despite the resistance I’ve met from other people who’ve also lived through it—has yielded unexpected gifts: I learned recently that when Byran was sentenced to life in prison, Johnny’s mother embraced Byran’s mother in the courtroom, saying, “Today, we’ve both lost sons.”

It’s that kind of truth I’m searching for, in my letters to Byran and in telling the story. Johnny’s mother seems to have known that the only thing worse than losing your child is watching your child lose himself. She offered the compassion and the love that only she could offer. She is why I keep writing, even when I don’t know what to say.

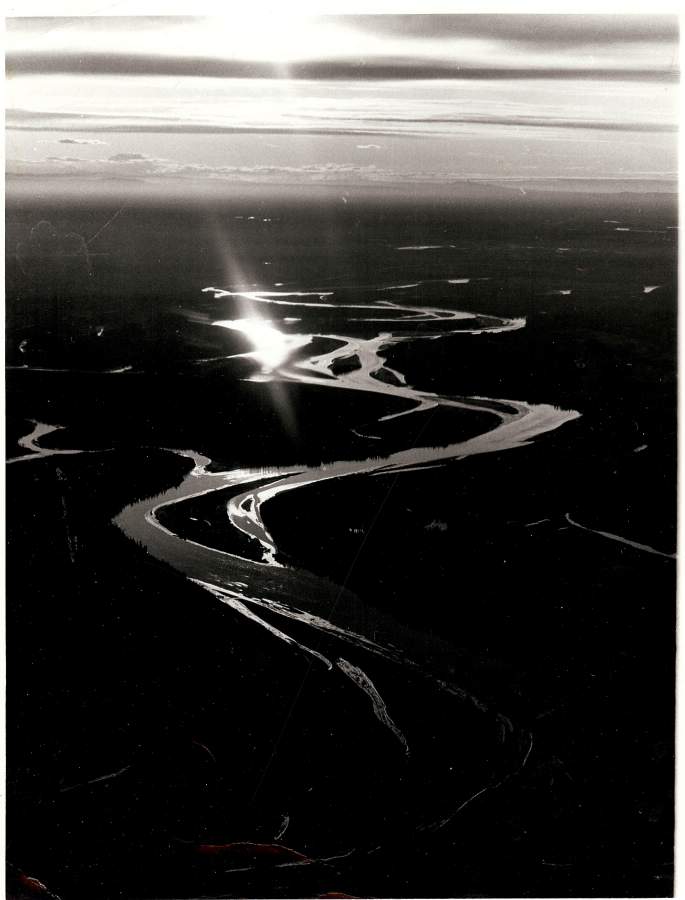

Lead Photo: The Tanana River with ice fog. (Photo: frostnip/Flickr)