Most Americans seem blissfully unaware and unconcerned that our frequent and routine exposure to high-decibel noise, much of which we’re directly responsible for, will ultimately make it impossible for us to ever hear certain sounds again. Say goodbye to wind rustling through the trees, water lapping at the edge of a brook, and bees buzzing around a hive. Perhaps one day technology and medical science will restore these sounds to those who have lost them, but current hearing aids don’t have this capacity: They serve mostly to help us communicate with each other and do little to help us communicate with the natural world. Meanwhile, at all ages, we are taking active steps to impair our hearing.

Start with infants, those humans you might think are the least affected by loud sounds. Technology meant to positively alter their sonic universe in the short term may lead to negatively altering that universe permanently.

Earlier this month newspapers were filled with stories about a University of Toronto study. The first two sentences of the abstract say it all: “Infant ‘sleep machines’ (ISMs) produce ambient noise or noise to mask other sounds in an infant’s room with the goal of increasing uninterrupted sleep. We suggest that the consistent use of these devices raises concerns for increasing an infant’s risk of noise-induced hearing loss.” Parents trying to block out disturbing environmental noise may unwittingly be making their infants hard of hearing.

Hearing-damaged infants become hearing-damaged teenagers who listen to loud music that further damages their hearing, who then become hearing-damaged adults who go to events that further damage their hearing, who then have children whose hearing is damaged because their parents cannot hear.

This study fits a larger pattern: Hearing-damaged infants become hearing-damaged teenagers who listen to loud music that further damages their hearing, who then become hearing-damaged adults who go to events that further damage their hearing, who then have children whose hearing is damaged because their parents cannot hear.

Humans have known for millennia that loud sounds can induce hearing loss, but the past two centuries have ushered in new challenges to our ears. The Industrial Age has led to increased exposure to loud sounds in the workplace and the urban landscape. Add electricity to the mix and its ability to amplify sound, and today we live in a world where exposure to high-decibel noise is almost unavoidable.

But much of this exposure occurs by choice. Fewer and fewer Americans today experience loud sounds because their workplaces are inherently noisy; at the same time, more and more Americans experience loud sounds because their leisure activities are, literally, deafening.

The American Academy of Audiology circumspectly assesses exposure to loud music, saying that “any genre of music” can expose an individual to unsafe levels of sound. Certainly a climax in a Mahler symphony or a session of African drumming can be ear-splittingly loud. But I sense that, while these audiologists may not have wanted to get into the genre wars, they needn’t have worried. Studies have repeatedly shown that Americans’ listening habits have exposed us to hours of loud music daily often delivered through headphones and ear buds that, in turn, has led to hearing loss.

This is particularly acute in teenagers. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention say that listening to a personal stereo system (such as an iPod with ear buds) at high volume can produce sounds around 105dB and recommend reducing exposure to no more than five minutes at a time. Yet another study shows that teenagers listen to over three hours of music per day. No wonder Apple encourages iPod owners to listen responsibly and limit the time one listens to music. “If you experience ringing in your ears or hear muffled speech, stop listening and have your hearing checked,” a page devoted to the subject on the company’s corporate website reads.

Self-inflicted hearing loss comes from sources other than headphones. Last year the Seattle Seahawks made news when they set a record for being the loudest outdoor football stadium in the nation. Fans were asked to ramp up the noise, at one point reaching 136.6dB. The Kansas City Chiefs responded, besting the Seahawks and registering 137.5dB. The twelfth man roared back in Seattle, squeaking past Kansas City by one-tenth of a point.

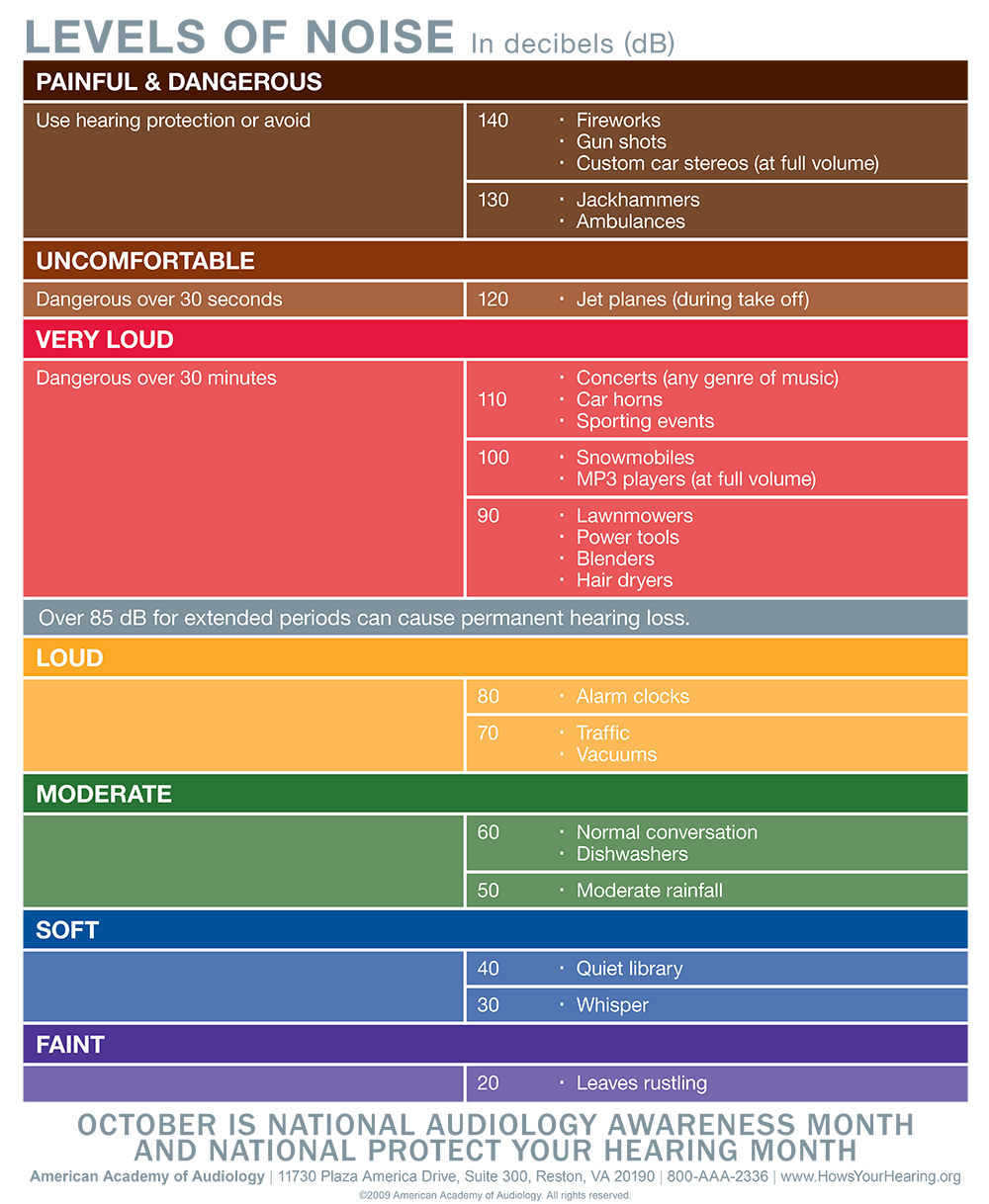

A chart created by the American Academy of Audiology suggests most sporting events register around 110dB. That same chart notes that sounds over 120dB are dangerous if exposure lasts longer than 30 seconds; sounds over 130dB include jackhammers, ambulance sirens, and custom car stereos at full volume. So for football: If deafness is the end zone, stadiums are running up the score.

It’s not only sporting events and car stereos where loudness reigns. Consider how loud the average ovation has become at a student concert, wedding banquet, or going-away party. Polite applause and the occasional vocal approbation once sufficed. Now we compete with each other to see who can make the most noise in order to express appreciation. Quietly lurking behind these whistles and hoots—and given our current state, we may not have heard the thought—lies the possibility that ovations are louder today because we cannot hear ourselves.

We’re not just in jeopardy of losing sounds in nature. There are larger societal costs as well, as we run the risk of experiencing a twist on the old axiom: Out of hearing, out of mind. If we cannot hear the sounds that nature makes, we discount the importance of nature’s abilities to make those sounds. We can come to care less about the air and the water and the birds and the bees all because—to paraphrase and rearrange Shakespeare—we cannot hear the sounds of music as they creep in our ears. Soft stillness and the night no longer become, for many, the touches of sweet harmony, potentially leading to discordant interactions with the world around us.

I recognize that, at some level, calling on us all to turn the sound down will fall on deaf ears. I trust nonetheless that I have reminded us why this is so.