There are hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese families living in America today, and they all have extraordinary stories about immigrating in the aftermath of the Vietnam War. Lana and Nam Luu’s experience stands out among them. The pair married in 1975, just weeks before the Communist North won the war. Nam, a police major for the South Vietnamese government, was sent to a re-education camp; Lana fled to the United States. She wound up waiting 15 years, without re-marrying, to be re-united with her husband.

On this Valentine’s Day, deep in an election year where immigration is a hot topic, here’s a story of one immigrant couple’s efforts to re-unite and establish a life for themselves in America. Lana and Nam, who are friends with my parents, live in Orange County, California. They have a 25-year-old son, Duane, who was born in the U.S.

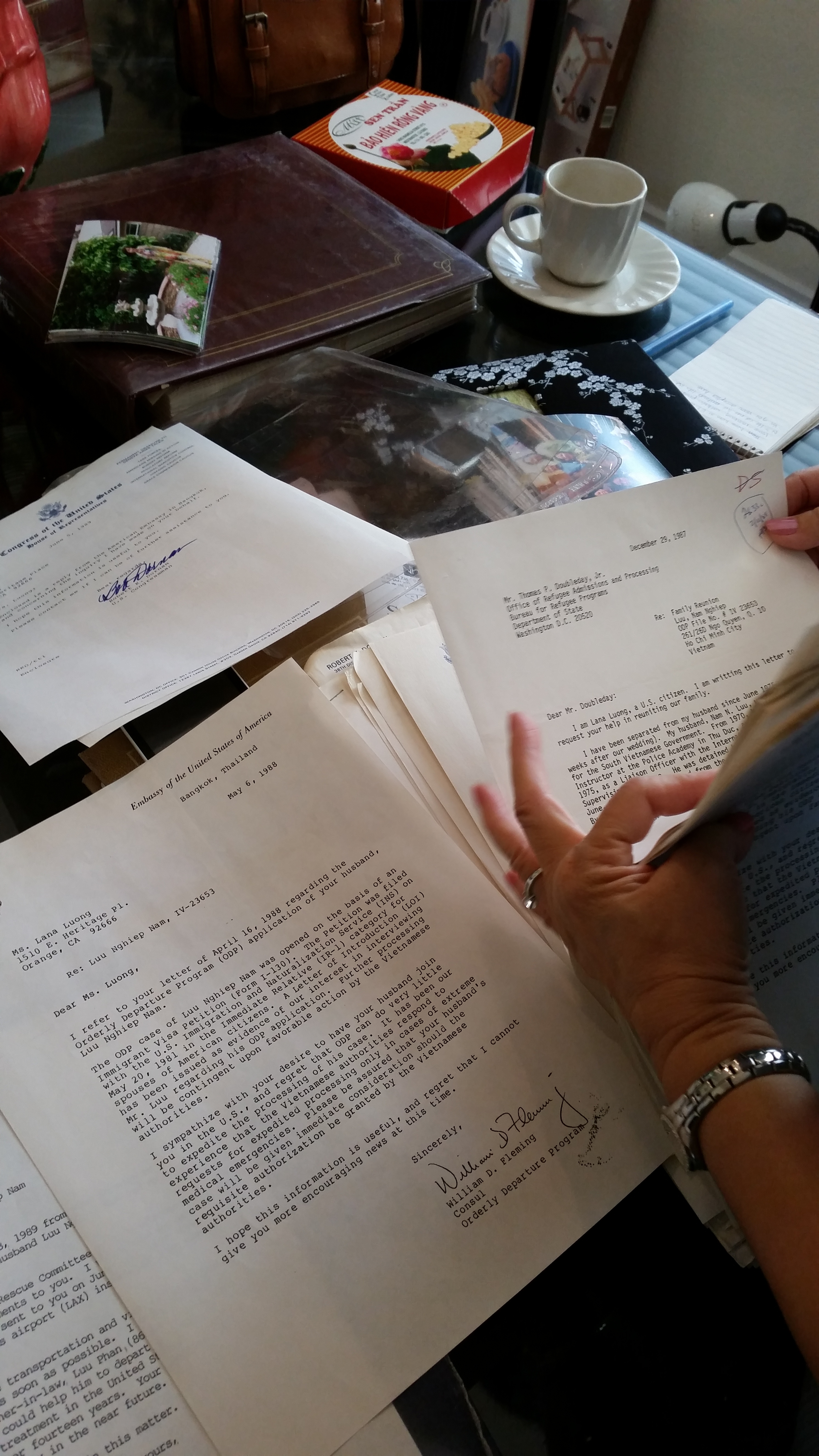

Support, and sometimes the lack thereof, from American politicians played a crucial role in Lana and Nam’s fate. Lana first obtained an entry permit for Nam so that he was able to come into the country with documentation. But the Vietnamese government wouldn’t allow Nam to leave. Lana wrote to various local politicians, asking for help. (She showed me inches-thick stacks of copies of letters she sent, year after year.) Finally, Congressman Robert Dornan (R-California), well known for his controversial comments on minority groups, lent his weight to her petition. With Dornan’s support, Lana’s efforts were ultimately successful.

Below, a conversation with Lana and Nam.

Lana, what was it like fleeing Vietnam?

Lana Luu: Our boat was just about 26 meters long and we had over 600 people. So we were like sardines. We could not lie down all at the same time. My sister-in-law had a baby who had only a few hairs. Even the baby had lice.

We ran into Thai pirates three or four times. One person on the boat was a jewelry store owner. They brought a lot of diamonds, hidden in a Buddha statue. The first time we were boarded, the pirates broke the Buddha. They got the diamonds. They didn’t touch any people. But the second time—you know, my family had a cabin on the boat, but when the pirates came, I ran below deck. But they pulled me out, into their pirate boat. I was so scared. I remember it was in the dead of night. No light, no sun, no moon.

Two pirates came right in front of me and put a flashlight right in my face. I didn’t open my eyes. I pretended I was sleeping, and I was holding this little girl, who really was asleep. I heard the pirates laugh and then they left. They were looking for unmarried women and they thought I already had a daughter.

That night, 15 girls were raped. I know I’m very lucky.

After we got here to America, for many years, I sent that little girl gifts on her birthday and Christmas. Now she’s over 40 years old.

So that’s why after I came here, I told my husband, “Don’t escape by boat. Wait for the legal papers.”

I came to America in 1979. By 1981, I already had an entry permit for him to come, but the Communists would not allow him to leave until 1989.

Nam Luu: [Dornan] went on a trip to Vietnam and he brought with him a list of prisoners, to ask the Vietnamese government to let us go.

Lana: After Nam got here, I made a cake and I brought it to Congressman Dornan’s office.

So when you left Vietnam on that boat, you didn’t know whether your husband could ever come to America.

Lana: Yeah.

Nam: It was very difficult to tell how long it would be before we were re-united.

How did you decide that Lana would wait?

Lana: Some of his friends told their wives, “Don’t wait for me anymore,” but he never told me that. But I believed on faith. I thought if I could wait for him, then in the future—because my family is Buddhist, I believe if you do something good, then you will get something good later.

Too many of his friends went home [to find] their wives had already re-married.

We believe a husband and a wife have a connection, maybe from the last life.

Did you have other friends like you, who had to wait many years for the husband to get out of prison?

Lana: Some of his friends had similar situations.

Nam: But not 15 years. They re-united after about six or seven years of separation because their wives stayed in Vietnam. So after they got out of the prison, they were re-united.

Lana: He was imprisoned for eight years and four months. One hundred months. And after they released him, he had to wait for the exit permit [from the Vietnamese government]. He already had the entry permit [from the American government].

Nam, what was the re-education camp like?

Nam: Before entering into the Communist camp, I weighed 60 kilograms. I lost about 20 kilograms. Many of our friends died in there, during that time.

What did you do most of the day?

Nam: Oh my God, hard labor, outside. Till the land. Work in the rice fields. They gave us hammers to break rocks into small pieces, for construction or something. Or sometimes, they would have us do that for nothing.

Almost every night, we had to meet. You know what for? For brainwashing. Every night, they had us read newspapers that talked badly about capitalism and praised their Communist regime.

There was a very famous Vietnamese musician there. He composed many new songs denigrating the old regime and the American people. They obliged us to sing the songs every night.

But they never could brainwash us. They knew that. We were too old to be brainwashed.

One of our heartbreaks was that, among us, there were some bad people. Whatever we told each other, whatever we did, they reported it to the officers of the camp. Our friends killed us. I don’t know how to say that kind of people in English. In Vietnamese, we usually use the world antenna.

These antenna, were they people who were originally imprisoned by the Communist government?

Nam: Yeah, like us. But they thought that by doing that, they could be released earlier, but no—they were wrong.

While you were in the camp and Lana was in the U.S., you kept in touch by sending letters to each other. Do you still have any of those letters?

Lana: Yeah, a whole box. I put the letters he sent me in a red box, to give to him as a gift when he came here.

How did you feel when you landed in the airport in Los Angeles?

Nam: We felt very happy. Speechless, you see? We didn’t talk much.

Did you recognize her?

Nam: Of course, because we exchanged pictures all the time.

And you had another wedding?

Lana: When he came here from Vietnam, we had a second wedding. Long ago, I had gone to a fortune teller. She said I would have to have two weddings in my life, so I considered this my “second wedding.”

Now you have a son, Duane. How did you come up with his name?

Nam: Oh, that’s a story too.

Tuan ju, in Chinese, means re-unification. The sound of “Duane” is close to “tuan.” And his middle name is Gia, [which] means family.

Lana: The meaning is like “family reunion,” in Vietnamese and Chinese.

Nam: To celebrate our re-unification.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.