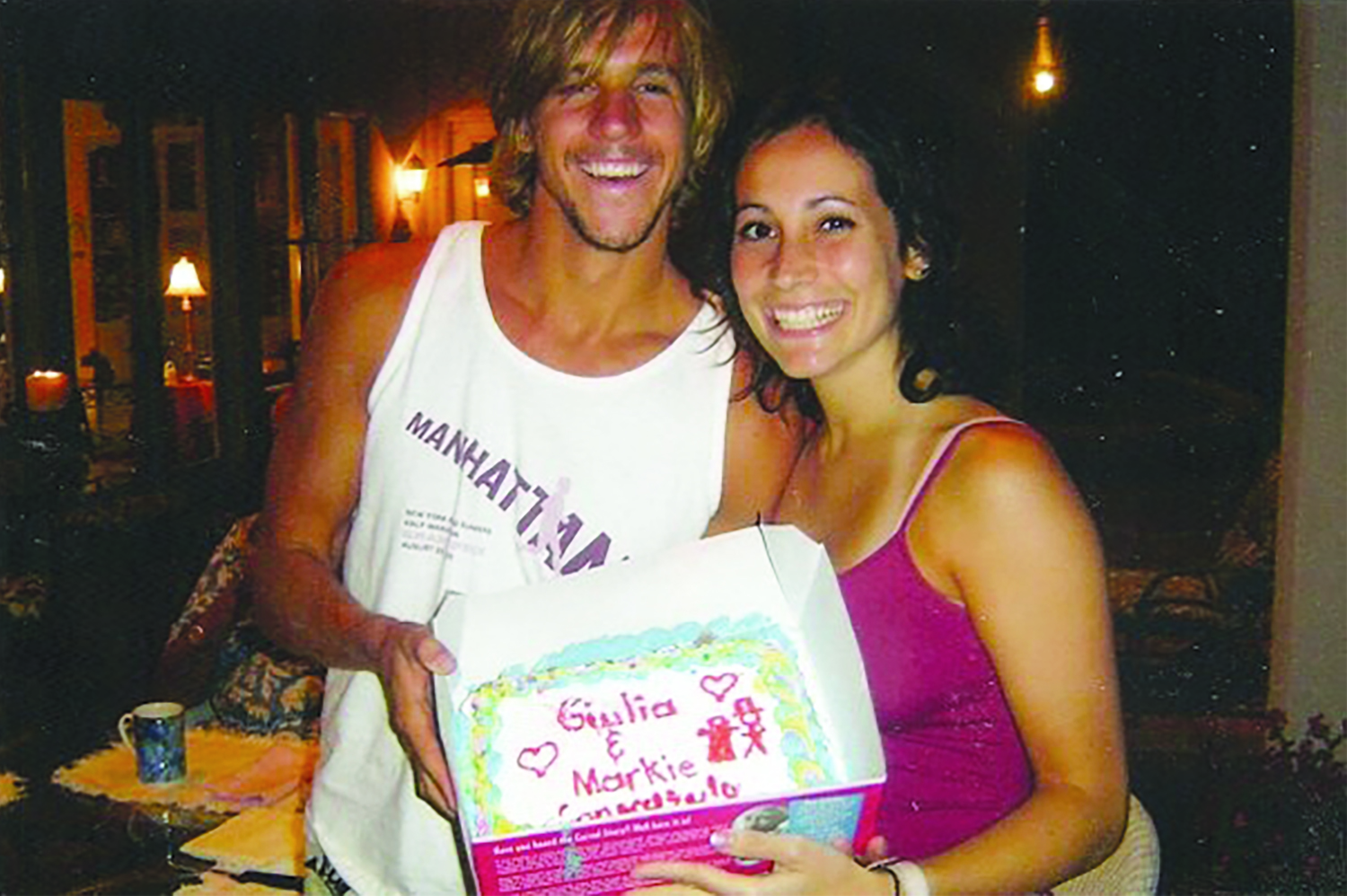

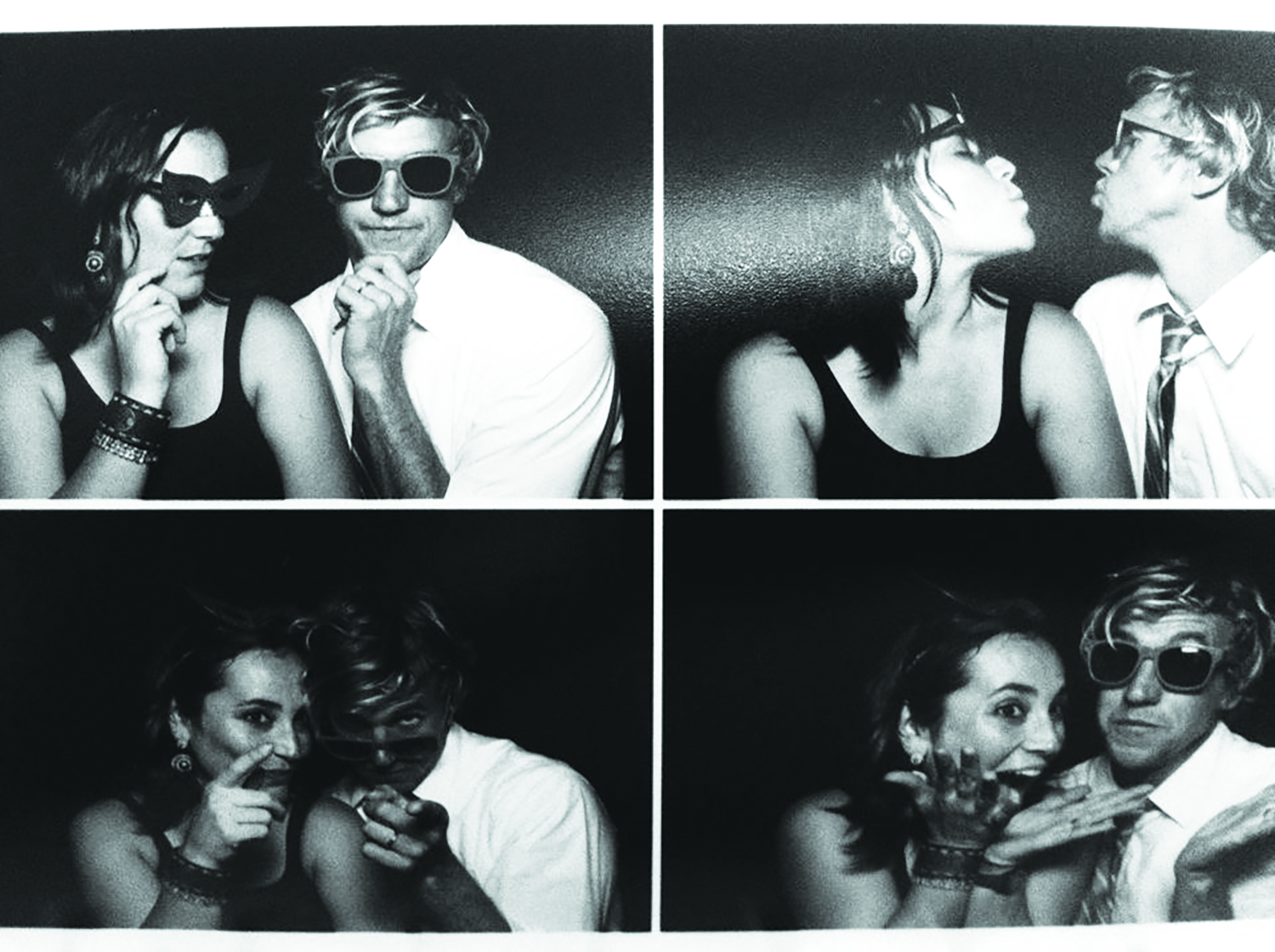

The first time I saw my wife walking around the Georgetown campus I shouted out “Buongiorno Principessa!” like a buffoon. She was Italian, radiant, way out of my league, but I was fearless and almost immediately in love. We lived in the same freshman dorm. She had a smile bello come il sole—I learned some Italian immediately to impress her—and within a month we were a couple. She’d stop by my room to wake me up if I was oversleeping class; I taped roses to her door. Giulia had a perfect GPA; I had a mohawk and a Sector 9 longboard. We were both blown away by how amazing it feels to love someone and be loved back.

Two years after graduation we married, when we were both just 24 years old and many of our friends were still looking for first jobs. We packed our separate apartments into one moving truck and told the driver, “Go to San Francisco. We’ll give you an address when we find one.”

One night, as I approached Giulia’s room, she saw me and collapsed on her bed, chanting “Voglio morire, voglio morire, voglio morire.” I want to die, I want to die, I want to die.

Giulia had a concrete life plan: to become a director of marketing at a fashion company and have three kids by the time she turned 35. My ambitions were looser: I wanted to bodysurf hollow waves at San Francisco’s Ocean Beach and enjoy my job teaching high-school history and coaching soccer and swimming. Giulia was focused and practical. My head was often in the clouds, if not the water. After a few years of marriage, we started talking about having the first of those three babies. By our third anniversary our charmed adolescence was transforming into a charmed adulthood. Giulia landed a dream job.

This is where that lovely storyline ends.

After only a few weeks in her new position, Giulia’s anxiety level rose beyond anything I’d ever seen. She’d always been a bit high-strung, holding herself to impeccable standards. Now, at age 27, she was petrified, actually frozen—terrified of disappointing people and making the wrong impression. She’d spend all day at work trying to compose a single email, forward the text to me to edit, and still not send it. Her mind lost room for anything but worries. At dinner she stared at her meal; at night she stared at the ceiling. I stayed up as late as I could, trying to comfort her—I’m sure you’re doing a great job at work, you always do—but by midnight I inevitably dozed off, racked by guilt. I knew that while I slept, my sweet wife was trapped awake with her horrible thoughts, uncomfortably awaiting morning.

She saw a therapist, then a psychiatrist who prescribed antidepressants and sleeping pills, which we both naively thought was a huge overreaction. She wasn’t that bad off, right? Giulia chose not to take the pills. Instead, she called in sick to work. Then one night, while we were brushing our teeth, Giulia asked me to hide her medications, saying, “I don’t like having them in the house and knowing where they are.” I said sure, of course, but in the morning I woke up late and rushed off to school, forgetting her request. At the time I thought this was a minor oversight, like misplacing my wallet. But Giulia spent the day at home staring at her two orange bottles of pills and daring herself to eat them all. She didn’t call me at work to tell me this—she knew I would have come straight home. Instead she called her mother, in Italy, who stalled on the phone with Giulia for four hours until I returned.

The next morning I woke to find Giulia sitting on the bed, calmly but incoherently talking about the conversations she had overnight with God, and the panic set in. Giulia’s parents were already on a plane to California from Tuscany. I phoned the psychiatrist, who said, again, to take the medication. By now I thought that was a great idea—this crisis was clearly way beyond my depth. But still, Giulia refused the meds. The next morning, when I woke, I found her pacing around our bedroom, relating her animated chats with the devil. That was enough. With Giulia’s parents, who by then were in town, I drove her to the Kaiser Permanente emergency room. Kaiser didn’t have an inpatient psychiatric unit, so they sent us to Saint Francis Memorial Hospital, in downtown San Francisco, where Giulia was admitted. We all thought her stay in the psych ward would be brief. Giulia would get a little pharmaceutical help; her brain would clear up within days, maybe hours. She’d be back on track to her director-of-marketing goal and her three kids before age 35.

That fantasy shattered in the waiting room. Giulia was not going home today or tomorrow. Looking through the glass window into Giulia’s new, horrifying home, I asked myself, What the hell have I done? The place was full of potentially dangerous people who would rip apart my beautiful wife. Besides, she wasn’t really crazy. She just hadn’t slept. She was stressed. Probably anxious about work. Nervous about the prospect of becoming a parent. Not mentally ill.

Yet my wife was ill. Acutely psychotic, as the doctors put it. She existed in an almost constant state of delusion, consumed by paranoia that would not fade. For the next three weeks I visited Giulia every night during visiting hours, from 7:00 to 8:30 p.m. She ranted unintelligible babble about heaven, hell, angels, and the devil. Very little she said made sense. One night, as I approached Giulia’s room, she saw me and collapsed on her bed, chanting, “Voglio morire, voglio morire, voglio morire.” I want to die, I want to die, I want to die. At first she hissed this through her teeth, then started shouting “VOGLIO MORIRE, VOGLIO MORIRE” in an aggressive roar. I’m not sure which scared me more: listening to my wife scream her death wish or whisper it.

I hated the hospital—it sapped me of all energy and optimism. I can’t imagine what it was like for Giulia. She was psychotic, yes, and tormented by her own thoughts, and she needed care and help. And for her to get that care she was locked up against her will and pinned down by orderlies who injected medicine into her hip.

“Mark, I think this is worse than if Giulia had died,” my mother-in-law said to me one night after leaving Saint Francis Memorial. “The person we visit is not my daughter, and we don’t know if she is coming back.” I was silent, but agreed. Every evening I ripped open a wound that I’d spent the whole preceding day trying to patch up.

Giulia stayed in the hospital 23 days, longer than anyone else on her ward. Sometimes Giulia’s delusions scared her; other times they assured her. Finally, after three weeks on heavy antipsychotic medications, the psychosis began to lift. The doctors still didn’t have a firm diagnosis. Schizophrenia? Probably not. Bipolar disorder? Unlikely. At our discharge meeting, the doctor explained to me how important it was for Giulia to take her medication at home, and how this might be difficult because I couldn’t forcibly inject it the way the orderlies did in the hospital. Meanwhile, Giulia still slipped in and out of delusions. During that meeting, she leaned over and whispered to me that she was the devil and needed to be locked up forever.

There’s no handbook on how to survive your young wife’s psychiatric crisis. The person you love is no longer there, replaced by a stranger who’s shocking and exotic. Every day I tasted the bittersweet saliva that signals you’re about to puke. To keep myself sane I hurled myself at being an excellent psychotic-person’s spouse. I kept notes on what made things better and what made things worse. I made Giulia take her medicine as prescribed. Sometime this meant watching her swallow, then checking her mouth to confirm that she hadn’t hidden the pills under her tongue. This dynamic led us to become less than equals, which was unsettling. As I did with my students at school, I claimed an authority over Giulia. I told myself that I knew what was better for her than she did. I thought she should bend to my control and act as my well-behaved ward. This didn’t happen, of course. Psychotic people seldom behave. So when I said Take your pills or Go to sleep, she responded badly, often with Shut up or Go away. The conflict between us extended to the doctor’s office. I thought of myself as Giulia’s advocate, but often, with her physicians, I didn’t side with her. I wanted her to follow medical advice that she herself did not want to follow. I’d do anything to assist her doctors with their treatment plan. I was there to help.

“Mark, I think this is worse than if Giulia had died,” my mother-in-law said to me one night after leaving Saint Francis Memorial. “The person we visit is not my daughter, and we don’t know if she is coming back.”

Once discharged, Giulia’s psychosis lasted another month. It was then followed by an eight-month-long haze of depression, suicidality, lethargy, and disengagement. I took a few months off of work to be with Giulia during the day and keep her safe, even get her out of bed. Throughout, her doctors kept tweaking her meds, trying to find the best combination. I took it upon myself to make Giulia take her pills as prescribed.

Then, finally, almost abruptly, Giulia was back. Her psychiatrists told us that her long episode was probably a one-and-done thing: major depression with psychotic features—a dressed-up term for a nervous breakdown. We needed to be proactive and careful about Giulia maintaining balanced and stable habits. That meant her staying on the pills, going to bed early, eating well, minimizing alcohol and caffeine, exercising regularly. But once Giulia returned to health we greedily inhaled our normal lives—windy walks on Ocean Beach, actual intimacy, even the luxury of stupid, meaningless fights. Soon enough she was interviewing for jobs, and landed a position even better than the one she had left when she was hospitalized. We never considered the possibility of a relapse. Why would we? Giulia had been sick; now she was better. Preparing for further illness felt like courting defeat.

Strangely, though, when we tried to return to our pre-crisis lives, we found that our relationship had flipped. Giulia was no longer the Type A partner who sweated the details. Instead, she was focused on living in the moment and being grateful for her health. Now, out of character, I was a stickler, the Felix who dwelled on nitty-gritty. This was weird, but at least our roles still complemented each other, and our marriage hummed along. So much so that a little over a year after Giulia’s return to sanity, we consulted with her psychiatrist, therapist, and OB/GYN, and Giulia got pregnant. Not even two years after I delivered Giulia to the psych ward, she gave birth to our son. During Giulia’s five-month maternity leave, she swooned, soaking up all the tiny glory that was Jonas—his smells, his doe eyes, his lips that puckered when he slept. I ordered diapers and enforced a schedule. We agreed that Giulia would return to work and I’d be the stay-at-home parent, writing while Jonas napped. That was great—for 10 days.

After just four sleepless nights, Giulia became psychotic again. One week she was skipping lunch in order to pump breast milk while FaceTiming me and Jonas. The next she was chattering compulsively about grand plans for the universe. I packed a bag of bottles and diapers, buckled Jonas into his car seat, cajoled Giulia out the door, and again drove to the ER. Once there, I tried to convince the on-call psychiatrist that I could handle this. I knew how to care for my wife at home, we’d done this before, all we needed was the same antipsychotic medication Giulia had done well on in the past. The doctor disagreed. She sent us to El Camino Hospital Mountain View, an hour’s drive south from our house. There, a doctor instructed Giulia to nurse Jonas one last time, before she took the meds that would poison her breast milk. As Jonas ate, Giulia prattled on about how heaven was a place on Earth and how God had a divine plan for everyone. (This may sound comforting, but trust me: It wasn’t.) Then the doctor took Jonas from Giulia, handed him to me, and took my wife away.

A week later, while Giulia paced in the psych ward, I visited our friends Cas and Leslie in Point Reyes. Already, Cas knew, I was worrying about falling back into my role as Giulia’s keeper, the psychiatrist’s enforcer. As we walked through a swampy marsh near California’s spectacular coast, Cas pulled out of his back pocket a small paperback book and offered it to me. “There might be another way,” he said.

The book, R.D. Laing’s The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness, was my introduction to anti-psychiatry. The book was published in 1960, when Laing was just 33 years old and drug treatment was becoming a dominant practice in the treatment of mental illness. Laing clearly didn’t like the shift. He didn’t even like the assumption that psychosis was a disease that needed to be cured. In an argument that in some ways predicted the contemporary neurodiversity movement, Laing wrote, “The cracked mind of the schizophrenic may let in light which does not enter the intact minds of many sane people whose minds are closed.” To him the strange behavior of psychotics was not de facto bad. Perhaps they were making legitimate attempts to communicate thoughts and feelings that conventional society did not permit? Could it be that family members, as well as doctors, defined certain people as crazy in order to discredit them? Seen from Laing’s view, the construction of mental illness is demeaning, even dehumanizing—a power grab by the supposed normals. I found The Divided Self extremely painful to read. Among its most searing lines for me: “I have never known a schizophrenic who could say he was loved.”

Psychiatric crises are episodic, but they cut deep into relationships and the lacerations take years to mend.

Laing’s book helped spawn the Mad Pride movement, which modeled itself on gay pride, reclaiming the word mad as a positive identifier instead of a slur. Mad Pride came out of the psychiatric survivor movement, with its goal of taking mental health treatment decisions out of the hands of doctors and well-intentioned caregivers and putting those decisions into the hands of patients. I admired all of those rights movements—every person deserves acceptance and self-determination, as far as I’m concerned—but Laing’s words hurt. I’d made loving Giulia the center of my life. I put her recovery above all else for almost a year. I wasn’t ashamed of Giulia. Just the opposite: I was proud of her and how she fought her illness. If there was a green or orange psychosis-supporter ribbon, I would have worn it.

Yet Laing ripped through a conception I had of myself that I held dear: that I was a good husband. Laing died in 1989, more than 20 years before I picked up his book, so who knows what he really would have thought. His ideas about mental health and its treatment could have shifted with the times. But in my admittedly sensitive state, I felt Laing saying: Patients are good. Doctors are bad. Family members botch things up by listening to physicians and becoming bumbling accomplices in the crime of psychiatry. And I was an accessory, conspiring to force Giulia to take medication against her will that made her distant, unhappy, and slow, and that silenced her psychotic thoughts. That same medication enabled Giulia to remain alive, so everything else was secondary, as far as I was concerned. I never doubted the rightness of my motives. From the beginning, I’d cast myself in the role of Giulia’s self-effacing caregiver—not a saint, but definitely a guy working on the side of good. Laing made me feel like I was her tormentor.

Giulia’s second hospitalization was even harder than the first. On the quiet nights I spent at home, after Jonas fell asleep, the reality hit: This isn’t going away. In the psych ward Giulia took to collecting leaves and scattering them throughout her room. When I’d visit, she’d unleash a flood of paranoid questions and accusations, then bend down and scoop up the leaves and inhale, as if the smell might anchor her thoughts against floating away. My mind raced, too. Laing’s ideas raised so many questions. Should Giulia even be in the hospital? Was this an actual illness? Did the pills make things better or worse? All these queries piled self-doubt on top of my sadness and fear. If Giulia had a disease like cancer or diabetes, she’d guide her own treatment; because she was mentally ill, she didn’t. Nobody even put much stock in Giulia’s opinions. And psychiatry is not a field with rock-hard data behind its diagnoses and treatment plans. Some of the most prominent leaders in psychiatry have recently lambasted their own discipline for its inadequate research basis. In 2013, Thomas Insel, the director of the National Institute of Mental Health, criticized the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, psychiatry’s so-called bible, for lacking scientific rigor—in particular, for defining disorders based on symptoms instead of objective measures. “In the rest of medicine,” he said, this would be considered antiquated and insufficient, “equivalent to creating diagnostic systems based on the nature of chest pain or the quality of fever.” Allen Frances, who oversaw the 1994 edition of the DSM and who later wrote the book Saving Normal: An Insider’s Revolt Against Out-of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life, put it even more bluntly: “There is no definition of a mental disorder. It’s bullshit.”

Still, Giulia’s doctors, parents, and I made decisions for her. She continued to hate the pills we all forced her to take, and she emerged from her second psychosis much the same way she did her first: with the aid of meds. She returned home after 33 days, still intermittently psychotic but mostly under control. She didn’t talk about the devil or the universe anymore, but, once again, she was barely there, lost in depression and a chemical fog.

During her recovery Giulia attended group therapy, and sometimes her friends from that group came over to our place. They’d sit on our couch and commiserate about how much they hated their pills, their doctors, and their diagnoses. This made me uncomfortable, and not just because they nicknamed me the Medicine Nazi. Their conversations were informed by the anti-psychiatry movement, and that movement is founded on the idea of patients supporting patients—or psychiatric survivors supporting psychiatric survivors, as they call themselves—regardless of whether those survivors are good influences or not. This terrified me. I feared Giulia’s recovery being taken out of the hands of sane, compassionate people—i.e., her medical team, family, and me—and given over to people like herself, who might be psychotic or suicidal.

Unsure how to deal with this and frankly exhausted by our regular fights over taking her prescriptions and seeing her doctor, I called Sascha Altman DuBrul, one of the founders of the Icarus Project, an alternative medical health organization that “seeks to overcome the limitations of a world determined to label, categorize, and sort human behavior.” The Icarus Project categorizes what most people consider mental illness as “the space between brilliance and madness.” I didn’t feel great picking up the phone. I wasn’t seeing the brilliant side of Giulia’s behaviors, and I wasn’t eager for more judgment and guilt. But I needed a new way to think about our struggles. DuBrul instantly put me at ease. He started by arguing that each person’s experience with mental health is unique. This may sound obvious, but psychiatry, to some extent, has been built on generalizations. (That’s part of the critique from Insel, Frances, and others: Psychiatry, as it exists in the DSM, is just a directory of catchall symptom-based labels.) DuBrul didn’t like the idea of people’s singular experiences being stuffed in one of a handful of available boxes.

“I have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder,” DuBrul told me. “While that term can be really useful for explaining some things, it’s lacking in a whole lot of nuances.” He said he found the label “kind of alienating.” All that resonated with me. For Giulia, too, none of the diagnoses seemed quite right. In her first psychotic break, psychiatrists ruled out bipolar disorder; in her second, three years later, they were certain she was bipolar. Besides, DuBrul said, no matter the diagnosis, psychiatry “gives you terrible language for defining yourself.”

The doctor took Jonas from Giulia, handed him to me, and took my wife away.

As for medication, DuBrul said that he believed that the answer to the question of whether or not to use pharmaceuticals needed to be far more nuanced than yes or no. The best response might be maybe, sometimes, or only certain medications. For instance, DuBrul shared that he takes lithium every night because he’s confident that, after four hospitalizations and over a decade with the label bipolar, the medication is a positive part of his care. Not the whole solution, but a piece.

All this was very comforting, but I really perked up and started paying careful attention when DuBrul introduced me to the concept of mad maps. Like advanced directives for the dying, DuBrul explained, mad maps allow psychiatric patients to outline what they’d like their care to look like in future mental health crises. The logic is: If a person can define health, while healthy, and differentiate health from crisis, that person can shape his or her own care. The maps are not intended to be rejections of psychiatry, though they could be that. The maps are designed to force patients and family members to plan ahead—to treat a relapse as possible or even likely—in order to avoid, or at least minimize, future mistakes.

When Jonas was 16 months old, Giulia and I put a bottle of anti-psychotics in our medicine cabinet, just in case. This might seem reasonable, but it was silly. We hadn’t yet heard of mad maps, so we’d never discussed what a situation would have to look like for Giulia to take the pills, and that made the medication useless. Was she going to take them if she wasn’t sleeping enough? Or was she going to wait until she was already psychotic? If she waited until she was psychotic, she would also likely be paranoid, meaning that she wouldn’t take the pills willingly. Me convincing her to do so at that point would be almost impossible.

Let me lay out a scenario: Just a few months ago Giulia was painting furniture, at midnight. She usually goes to bed early, an hour or two after putting Jonas down. Sleep is important, and she knows it. I suggested she go to bed.

“But I’m having fun,” Giulia said.

“Good,” I said. “But it’s midnight. Go to bed.”

“No,” she said.

“You realize what this looks like, right?” I said.

“What are you talking about?”

“I’m not saying that you’re manic, but on the surface, this looks like mania. Staying up late, painting, feeling full of energy….”

Giulia exploded. “How dare you tell me what to do? Stop running my life! You’re not in charge.” The fight lasted days. Anything that echoes how we acted “when she was sick” can lead to trouble. We played nice in front of Jonas, but for the next 72 hours all tiny missteps triggered titanic reactions.

Then, a week after the painting fight, Giulia had a tough day at work. As we got in bed to go to sleep, she quietly said, “I’m scared about how stressed out I feel.”

I asked her what she meant. She stonewalled. “I don’t want to talk about it because I need to sleep, but I’m scared.”

Which in turn scared the hell out of me. She was worried about her mental health. I tried to swallow my anger and fear that she wasn’t taking care of herself. But I didn’t sleep, and I blamed it on her, and we fought for another few days.

Giulia has been healthy for over a year now. She’s thriving at work, I’m back in teaching, we adore our son Jonas. Life feels good. Mostly.

Giulia takes a medicine dosage that seems to work without any uncomfortable side effects. But even during our best moments as husband and wife, father and mother, we can feel lingering traces of our roles as caretaker and patient. Psychiatric crises are episodic, but they cut deep into relationships and the lacerations take years to mend. When Giulia was sick, I acted for her in what I believed was her best interest, because I loved her and she wasn’t capable of making decisions for herself. On any given day during one of her episodes, if you asked, “Hey, what do you want to do this afternoon?” she might answer, “Throw myself off the Golden Gate Bridge.” I saw it as my job to keep our family together: pay bills, hold down a job, care for Giulia and our son.

And now, if I suggest that she go to bed, she complains that I’m telling her what to do, micromanaging her life. Which makes sense, because I did tell her what to do and micromanaged her life for months at a time. Meanwhile, I’m quick to gripe that she’s not taking care of herself well enough. This dynamic isn’t unique to us—it exists in countless other families who lived through a psychiatric crisis. The onetime caregiver continues to worry. The former (and perhaps future) patient feels trapped by paternalistic patterns.

I feared Giulia’s recovery being taken out of the hands of sane, compassionate people—i.e., her medical team, family, and me—and given over to people like herself, who might be psychotic or suicidal.

This is where mad maps offer a shard of hope. Giulia and I, finally, are trying to make one, and now that we’re doing so I have to concede that in some ways, Laing was right: The treatment of psychosis is about power. Who gets to decide what behavior is tolerated? Who chooses how and when to enforce the rules? We started trying to create Giulia’s map by discussing the pills in the medicine cabinet. Under what circumstances would Giulia take them, and how much would she take? I took a hardline approach: No sleep for one night, pills at maximum dosage. Giulia wanted more time before jumping to medication, and favored starting the dose out light. We argued bitterly as we outlined our positions and punched holes in each other’s logic. Ultimately we had to sit down with Giulia’s psychiatrist to figure it out. Now we have a plan—for one bottle of pills. It’s a small victory, but a genuine step in the right direction in a world where such steps are rare.

We still have a lot to decide, most of it tremendously complicated. Giulia still wants three kids before she turns 35; I’m interested in avoiding a third hospitalization. When we set aside time to talk about things, we know we’re making calendar space to fight.

But I believe in these talks, because when we sit down together to discuss medication dosages, or a timeline for getting pregnant, or the risks of taking lithium during pregnancy, we are essentially saying, “I love you.” My exact words might be “I think you’re rushing things,” but the subtext is “I want you to be healthy and fulfilled, and I want to spend my life with you. I want to hear how much you disagree with me, about something that is as personal as it gets, so that we can be together.” And Giulia might be saying, “Give me some space,” but in her heart it’s “I value what you’ve done for me, and I support you in everything you do, and let’s make this work.”

Giulia and I fell in love effortlessly, in our carefree teens. We’ve now loved each other desperately, through psychosis. At our wedding we promised this to each other: to love each other and stick together in good times and in bad. In hindsight, we also should have promised to love each other when life is normal. It’s those normal days, now transformed by crisis, that have strained our marriage most. I realize no mad map is going to keep Giulia out of the hospital, nor prevent us from fighting over her care. But the faith required to try to plan a life together feels good and grounding. I’m still willing to do almost anything to make Giulia smile.

For more on the science of society, and to support our work, sign up for our free email newsletters and subscribe to our bimonthly magazine. Digital editions are available in the App Store (iPad) and on Google Play (Android) and Zinio (Android, iPad, PC/MAC, iPhone, and Win8).

Lead photo by Larry Rosa.