When Monique Wisdom learned that her mother, Annette Kaiser, needed a life-saving kidney transplant, she didn’t hesitate to offer one of her own — after all, Kaiser had adopted Monique and her brother when their birth mother died of AIDS. But the 24-year-old loan officer had to think twice when she got a call one day last fall from Dr. A. Osama Gaber at The Methodist Hospital in Houston, where the transplant was to take place.

Gaber was proposing a swap: Wisdom would donate her kidney to a person she had never met, Jesus Martinez, a 36-year-old shipping and receiving clerk. In exchange, his wife Imelda, 33, would donate her kidney to Wisdom’s adoptive mother. “He said, ‘There’s another couple and the guy needs a kidney, and his wife wanted to donate, but she wasn’t a match,'” Wisdom recalls. “‘We were wondering, since you’re a match for your mother, it would be even better to be a match for him as well.'”

Wisdom and her mother talked it over for a couple of days. The idea of donating a kidney to a perfect stranger seemed strange — until Wisdom had a realization. “I thought, ‘What if I was in the same situation as them? Would somebody donate a kidney for me?'” she asks. “I’m sure they would do the same for me. That’s when I decided I should do it for them because I’m not only saving one life. I’m saving two.”

On a Friday morning in October, the Martinezes, Wisdom and Kaiser were wheeled into four operating rooms at Methodist, one of the many hospitals in the vast Texas Medical Center. Surgeons used minimally invasive laparoscopic techniques to remove the donors’ kidneys. Minutes later, Gaber, director of the hospital’s transplantation program, and Dr. Richard Knight began sewing the new kidneys into the recipients. When it was over, four lives were transformed.

“I have a lot more energy,” Kaiser says, still wearing a paper mask five weeks after the operation to protect her from infection because she’s taking large doses of immunosuppressant drugs. “As a matter of fact, my husband is telling me to slow down because I have so much energy, and I want to do so much around the house.”

Kidney transplants are the treatment of choice for people with end-stage renal failure, kept alive — barely — with weekly rounds of debilitating dialysis treatments. Nationally, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing, 27 million adults suffer from chronic kidney disease, and 78,000 people are awaiting transplants.

The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network reports that in 2007 a total of 16,628 transplants were performed nationwide, 10,587 in the form of kidneys harvested from the dead. Doctors prefer to use kidneys from live donors because on average they last nearly twice as long as transplants from cadavers. Most healthy adults can safely donate a kidney, so live donations are becoming more common — in 2007, 6,041 transplants came from live donors — but the need still outstrips the supply.

The National Organ Transplant Act of 1984 prohibits the sale of organs, so most live donations are between two people who know each other — husband and wife, parent and child or siblings. In the trade they’re known as direct exchanges. A sizable number of people without donors wind up on the waiting list for a cadaver transplant, but each time someone is removed from the list after receiving a live donation, the remaining people each move up a notch. In that sense, live donations are a net benefit to everyone.

And now, to increase the number of live-kidney transplants, doctors are turning to what are known as paired exchanges — like the one between the Martinezes and Kaiser and Wisdom — or even “chains” of exchanges among strangers that link together as many as 10 pairs of live donors and recipients. Hospitals, meanwhile, are forming networks to create as many potential donor-recipient matches as possible. But the push to find creative ways to boost the number of live transplants is also creating new logistical and ethical concerns.

One of the first transplant networks was the New England Program for Kidney Exchange, operating from the New England Organ Bank in Newton, Mass. To date, it has facilitated 38 transplants. In Ohio, transplant surgeon Dr. Michael Rees spearheaded the creation of the Alliance for Paired Donation, a consortium of 73 medical centers in 21 states that uses sophisticated software to find the optimal match between donors and recipients. Rees says he first learned about paired kidney donations at a meeting of the American Transplant Congress in May 2000. “I just thought it was a wonderful idea,” he recalls. He returned to the University of Toledo Medical Center, sat down with a piece of paper and tried to match the donors and recipients on his hospital’s transplant list. Four hours later, he came up with one potential paired donation — which fell apart due to tissue incompatibility.

Rees realized he needed to recruit other medical centers to create a bigger pool of potential donors. He also needed computer software to speed up the matching process and approached programmers to write the code. With a paltry $10,000 grant to pay for $50,000 worth of work, Rees was stymied until his father, a programmer, offered to take on the project as a Christmas present.

Rees worked for several years with the Ohio Solid Organ Transplantation Consortium, but he eventually decided the network needed to be national in scope, prompting him to found the nonprofit Alliance for Paired Donation in October 2006. The early computer programs were limited because as the number of potential donors increases, the number of possible combinations rises exponentially, Rees says. More recently, the alliance and the New England program have been using more sophisticated software based on an algorithm written by Harvard economist Alvin Roth and several colleagues. A leading expert in game theory and market design, Roth redesigned the system by which graduating medical students are matched with residency programs and created algorithms to match students with schools in Boston and New York City.

Roth says the problem of matching kidney donors with recipients is an example of a type of barter-based transaction that economists call “a double coincidence of wants.” In a market where money cannot change hands and people must trade for what they need, it is hard to discern what each party needs and is willing to give up.

Roth and his colleagues looked at research on finding the optimal way to assign dormitory rooms (where some rooms are empty, some people don’t have any rooms and some people with rooms might want better rooms) and realized that it was analogous to the problem of kidney donations. There are kidneys with no people (from deceased donors), people with no kidneys and people with kidneys.

Roth distinguishes between what he calls “cycles,” which include direct and paired donations, and “chains,” which potentially involve many more donations. Chains include indirect exchanges (also known as list exchanges), in which the donating member of an incompatible patient-donor couple gives a live kidney to someone on the list awaiting a cadaver kidney in return for the recipient member of the couple receiving a high priority on the waiting list.

Another kind of chain arises when someone who is unrelated to any of the recipients offers to donate a kidney for altruistic reasons. When that happens, a recipient’s partner donates a kidney to another recipient, whose partner donates a kidney to a third recipient, and so on. One chain facilitated by Rees’ alliance has led to a total of 10 transplants since July 2007.

Roth points out that not all recipients are created equal. To ensure success, live donors should be blood type-compatible with recipients, and the recipients should not have a positive cross match for antibodies to the donor kidney. Recipients sometimes develop antibodies due to prior blood transfusions or organ donations (and mothers may develop antibodies to their spouses and children because they exchange minute amounts of blood with their babies while giving birth). Whatever the reason, those willing to donate their kidney to a loved one often aren’t a suitable match.

People with the O blood type can donate to anyone — A, B and AB — but O recipients can only receive kidneys from O donors. That puts O recipients at a disadvantage. “That’s why we have to be careful about how we do the list exchanges,” Roth says.

He thinks that as networks increase in size (improving the prospects for hard-to-match recipients), the number of live donations will increase significantly — particularly if donors become accustomed to the idea of giving their kidneys to someone they don’t know. “I’d like to be able to write a letter to all of the people on the waiting list to say that an exchange is possible,” he says.

Rees says word of his program’s success has spurred some 250 potential altruistic donors to come forward to volunteer one of their kidneys. That poses a new problem because it costs about $5,000 to screen each one for his or her suitability to donate, and Rees lacks the money to pay for it. He has approached Medicare (which pays for the majority of transplants in the U.S.) about funding the screening, arguing that transplanting and maintaining a patient over time is much cheaper than keeping that person on dialysis (at a cost of about $80,000 per year). “I haven’t been able to talk the federal government into giving me a million bucks to make this work — it’s pathetic,” he says.

Meanwhile, he has launched several other long chains of donors, in which each person agrees to “pay it forward” when his or her loved one receives a kidney — with a novel twist. Although paired exchanges are conducted simultaneously to prevent one donor from backing out at the last minute and leaving the recipient at a disadvantage, in the chain donations Rees has opted for sequential transplants, sometimes carried out over a period of weeks or months. This eliminates the logistical hurdle of trying to book multiple operating rooms and surgical teams for simultaneous procedures.

While there is always a possibility that a donor will back out, Rees has concluded there is not much likelihood of cheating. “The kinds of people that are going to do this are a unique breed,” he says. “I just don’t believe that people willing to do that are going to cheat another family out of the miracle they’ve received.”

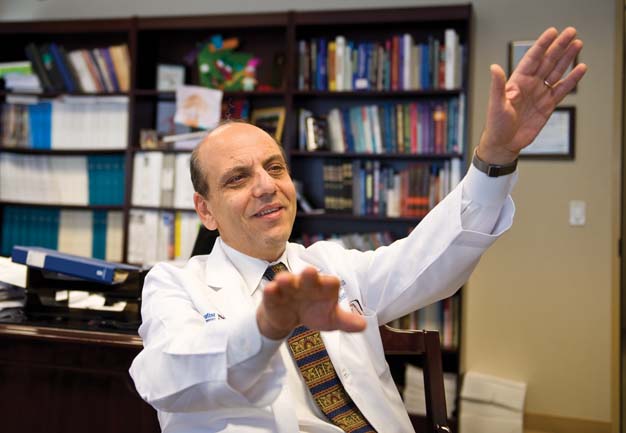

The first successful kidney transplant, between identical twins Ronald and Richard Herrick, was conducted by Dr. Joseph E. Murray in 1954. The 1960s were “the pioneer age,” as more surgeons tried their hands at transplants, abetted by a growing understanding of the immune response that led to organ rejection. When Osama Gaber received his medical training in the 1970s, kidney transplantation was becoming common.

Still, immunosuppressant medications and tissue-typing methods were imperfect. “We had the principles,” Gaber says. “We knew that to do transplants we needed several things. We needed to get the kidney outside of the body. We needed the medications to overcome the immune suppression system. We needed to tissue type the donor and the recipient. Based on that, you could do kidney transplantation in a semi-reliable fashion.”

When cyclosporine became the standard immunosuppressant drug in 1984, it was a game changer, he says: “We were able to do extra-renal transplants with predictable success. … It no longer became a technical exercise. It became a program.” Today, kidney transplantation is a routine procedure, with a 95-to-98 percent success rate, says Gaber, who chairs Texas Gov. Rick Perry’s Chronic Kidney Disease Task Force.

Last year, Methodist performed about 120 transplants, but a few years from now Gaber expects to see close to 400 annually. Meanwhile, the number of people with chronic kidney disease is projected to double in the next 10 to 15 years, partly due to an aging population and partly because of the “toxic” diet and lifestyles that cause hypertension and diabetes, both contributing causes of kidney failure, Gaber says.

Dialysis, which usually occurs several times a week, is an imperfect solution. For one thing, it fails to remove all the waste products that kidneys normally extract from the bloodstream and often leaves patients severely fatigued. Meanwhile, 7 to 10 percent of people on dialysis die each year; all told, about a third of the people on waiting lists will die before they get a kidney transplant.

Live donations have a higher success rate than transplants from cadavers, in part because the donated kidney spends very little time outside of the body, reducing the inflammatory process that can trigger organ rejection. They’re also less expensive than cadaver donations because they can be scheduled to reduce dialysis costs. Many doctors now recommend “pre-emptive transplants,” before patients get to the point of being severely affected by their renal disease. “Don’t wait until you need to go on dialysis because that’s the danger zone,” Gaber says.

Even after receiving transplants, patients will need a daily dose of immunosuppressant drugs for the rest of their lives. “They have lots of side effects,” he says. “But we have learned to use them in much smaller doses because we are using more effective combinations.”

These patients will also require ongoing medical monitoring, and they will always live with the fear of the unknown. “They know that rejection is something that lurks around the corner every time they come to the doctor, and they’re never certain that this is going to be just routine,” Gaber says. “I think that’s the only thing that keeps the quality of life from being the best that ever happened for those recipients.”

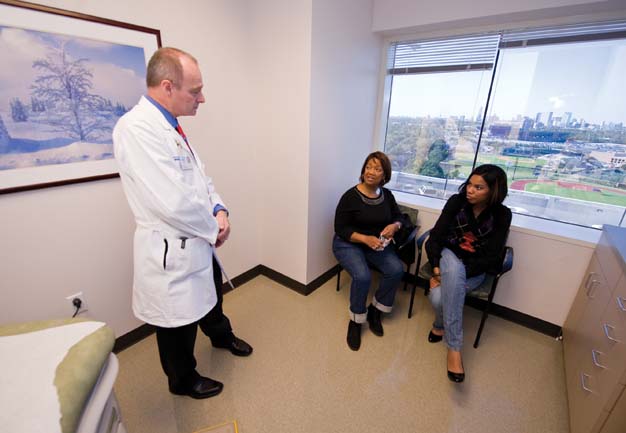

Monique Wisdom is slender and pretty, with a dazzling smile. She works in Dallas but has driven down to Houston to pay a post-surgical visit to the transplant team at Methodist along with her mother and the Martinezes. She was just 10 when her birth mother died and Annette Kaiser, a family friend, adopted her and her younger brother. “My mom didn’t want me and my brother separated because my biological dad was going to take me in custody but not him,” Wisdom says. “So it was really good that we stayed together and grew together.”

She figures she owes Kaiser her life, so she didn’t hesitate when she found out Kaiser needed a kidney donation. “She helped me, and now I’m helping her,” she says, simply.

Kaiser, 58, first learned she had a kidney disease called glumerial nephritis when she was in her early 20s. “I went on a trip to Spain, and when I came back, I was swollen,” she recalls. She controlled the condition for decades with medication, but her kidneys started deteriorating three years ago, and she started on dialysis in 2007. “I was fighting it,” Kaiser says. “I just knew it would be a change in my lifestyle.”

The dialysis treatments, which she received at home, were administered three days a week for four hours at a time. They left her feeling drained and miserable, unable to do anything but lie on the couch and watch television. “It was hard for me watching her because she was real sick,” Wisdom says. “Seeing that happen twice in my life — that was hard.”

Wisdom says she thought about donating a kidney to Kaiser after overhearing some patients discussing donations when she accompanied her mother to a doctor’s appointment. “I thought it would be good for her because it would help extend her life and help her live a normal life,” she says. “I went online and looked up the procedures — what it would take, the outcomes.”

She admits to worrying whether she would be able to have a baby with only one kidney, but the doctors put her fears to rest. The good news was that Wisdom, young and healthy, with an O positive blood type, was a suitable match for Kaiser, who was A positive. After the cross matching was completed, they scheduled the transplant.

Jesus and Imelda Martinez, both from Guadalajara, Mexico’s second-largest city, were raising their two sons in Houston when Jesus got the bad news that he was the latest in his family to fall prey to polycystic kidney disease, a hereditary condition. Six of 10 siblings have the disease. One brother died of it, while two of his brothers have had transplants. His twin sister and two other brothers are on dialysis.

Jesus, a shy, soft-spoken man, wound up on dialysis three days a week. As the sole support for his family, he never stopped working, even though he was exhausted and suffered cramps at night. “Sometimes I would try to play with my kids, but the tiredness would beat me,” he remembers.

When Imelda found out about her husband’s illness, she says, “I was crying, but I said, ‘God, if you send this disease, it’s OK if it’s your will.’ It was very sad.” She immediately offered to donate one of her kidneys to her husband.

Then lab tests showed she was an A positive blood type, while he was O positive, meaning he could not receive her kidney. When she found that out, she says, “I was crying. I was disappointed.” After doctors told them that another donor might be found for Jesus, she made regular calls to Nikki Eligio, the Spanish-speaking assistant in the Methodist transplant department.

Gaber says he had been thinking for some time about a paired exchange. “We are pushed by our patient needs,” he says. “I get people who walk into my clinic — they are in tears. They have been on dialysis for seven, eight, nine years. Their life is miserable, and they want a solution. They have a donor, but they’re just not the same blood group. We’ve got to find a solution for them.”

After learning that Imelda Martinez’s kidney would be incompatible with her husband’s, Gaber started looking for potential paired donors. When he compared their blood results to Kaiser’s and Wisdom’s, he realized each donor was a perfect match for the other recipient.

Meanwhile, Wisdom was already scheduled to donate her kidney to her mother. Gaber recalls, “I called Monique and said, ‘Your transplant is on schedule. It will go through, no matter what happens. So the question is, how about we make it bigger and better? I think that it’s a great thing, but I’ll put no pressure on you. You’ll have to decide it yourself.’ She really jumped at the idea and said, ‘Yeah, that would be neat.'”

After she and Kaiser were committed to the exchange, Eligio called Imelda Martinez to say a donor had been found. “I was happy,” Imelda says. “I didn’t know how to tell Jesus. I was screaming and crying.” She called her husband at work to deliver the good news. “He didn’t believe it at first,” Imelda says.

Sitting together in a conference room, Wisdom, Kaiser and the Martinezes recall their first meeting, two weeks prior to the surgery. “That’s when it kicked in,” Wisdom says. “It was really emotional. They were happy. We were happy to see them happy, and it felt good to help save lives.”

Jesus, who calls Wisdom “the angel,” jokes that after meeting her, “I feel like she’s part of our family, and they’re going to be naturalized as Mexicans.” Everyone laughs.

The increasing popularity of paired or chained kidney exchanges, while promising much, poses new challenges. Foremost is finding ways to expand the pool of potential donors to the point where patients with complicated antigen cross matches have the best chance of finding a compatible kidney. One approach lies in moving toward a national database of potential donors and recipients, maximizing the chance at a match.

Another is to recruit more altruistic donors, who have no connection with any of the recipients. In addition to initiating long chains of donations, like those Michael Rees has overseen, altruistic donors can also benefit recipients who lack donors of their own and otherwise would be consigned to the cadaver donor list.

Osama Gaber says transplant programs can only do so much to reach out to potential altruistic donors, however. “We as transplant centers have a conflict in trying to recruit,” he says. “(Donors) have to have some independent education, and somebody has to evaluate them to make sure they are doing it for the right reasons — that they understand the risks and the benefits before they even step into the transplant center.”

Gaber says he is collaborating with a Houston organization called The Living Bank, which promotes organ and tissue donation, in hopes that it will fulfill that essential role.

Meanwhile, new technology may also create new opportunities. In Japan, where for cultural reasons there are few cadaver transplants, doctors have pioneered live donor transplants across blood types, using a variety of methods, including using newly developed bio-absorption columns to filter antibodies from the recipient’s bloodstream. The Food and Drug Administration is evaluating the Japanese devices for possible use in the U.S., Gaber says.

The two Houston kidney donors arrived at the hospital the day before the surgery, and that evening, Jesus Martinez paid visits to both his wife and Wisdom. The next morning he and Kaiser checked in, and all four went off to surgery. Afterward, both Kaiser and Martinez had functioning third kidneys. (Doctors leave in the originals to spare surgical complications.)

They all spent about three days in the hospital. Imelda Martinez remembers being in pain but says, “Having children is more painful!” Meanwhile, she is relieved to see her husband on the road to recovery. Jesus says that when he emerged from surgery, “I felt stronger — and hungry.” He says he’s eager to return to work.

As for Wisdom’s generosity, he has a hard time finding the words to convey his gratitude. “I can’t express it,” he says. “It’s something big. I’ll always be thankful — always. All my life.”

Wisdom says it’s heartwarming to see how things have improved for the Martinezes, now that Jesus is feeling better. “It’s a happy family,” she says. “I feel good for them that they can have a normal life. I’m happy to see that they’re happy and that their families are happy for them. It’s just amazing.”

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.