During a recent meeting, officials at Covered California, the state’s much-touted health insurance marketplace, made a pretty stark admission: Half of the approximately one million consumers whose health plans are being canceled will pay more under the Affordable Care Act.

The numbers, it seems, have been overshadowed by other, more positive headlines. First, the state signed up more consumers in October than HealthCare.gov, the federal marketplace handling enrollments for 36 states. Second, the board governing Covered California voted not to allow insurers to offer their canceled policies for another year, rejecting President Obama’s recommendation earlier this month.

But the figures do call into question the sweeping plaudits California has received—including from New York Times columnist Paul Krugman in last Monday’s newspaper—for signing up so many people (about 80,000, as of last week).

By way of background, many of these consumers’ plans are being canceled because they were “non-grandfathered,” meaning they were purchased after the Act was signed by President Obama in March 2010 and their benefits do not meet its requirements (some were pretty skimpy).

Although the federal law allowed these plans to be renewed for another year, Covered California’s contracts with health insurers require them to be canceled at the end of this year. Officials said the idea was to create stability in the new marketplace and provide consistency for all consumers.

As cancellation letters went out, supporters of the law contended that the canceled policies either had inferior coverage or would cost far less in the exchanges. California’s numbers show that is only half the story.

“It’s not a success story,” said Jamie Court, president of Consumer Watchdog, a group that supports a California ballot measure to regulate insurance rates. “It’s a success story only if you consider that the federal website didn’t work and ours did. It’s not a success story because people are in open revolt about how much they’re paying. The only people who are happy are people who have subsidized policies. The middle class is outraged.”

Let’s look at the numbers:

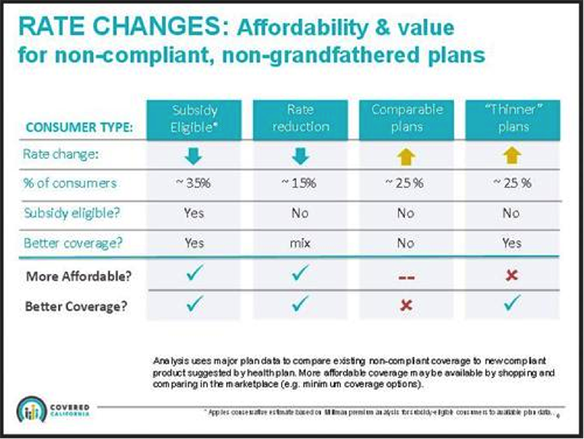

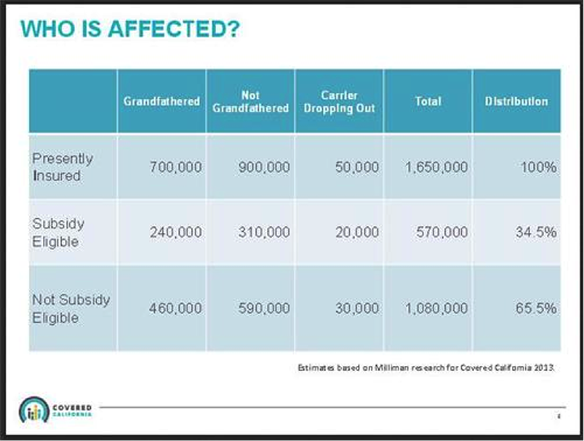

Covered California estimates that about 900,000 consumers will have their “non-grandfathered” policies canceled. Of those, 310,000 (or 35 percent) are eligible for a subsidy. Another 15 percent will see their rates decrease even though they won’t receive a subsidy. And the rest? About 25 percent will pay more for similar or perhaps inferior coverage, and the remaining 25 percent will pay more but will receive additional benefits, such as coverage for prescription drugs.

All told, fully half of the 900,000 will pay more. (I profiled one such couple, who will see their costs more than double, last month.) Additionally, while those receiving the subsidy will pay less out of their own pockets, their plans could still cost more and much of the tab will be picked up by the government.

Some other policies are being canceled, too, because insurers are withdrawing from the market.

Ken Wood, a senior adviser with Covered California, told me that the initial estimate of consumers in non-grandfathered plans was lower than the actual number because turnover in the individual insurance market was underappreciated.

“I’m not sure people fully understood the impact of the law three years ago when it was just numbers,” he said. “Now it’s gotten very real that some people are going to have to pay more.”

At the same time, Wood said, this is the cost of moving to a new system, in which consumers with pre-existing conditions will be able to get coverage, those who got sick while enrolled in a plan won’t have to worry about having their policies canceled, and all plans will offer a minimum set of benefits.

“Yes, they’re paying more than they would have paid,” he said. “That also assumed that their risk pool remained healthy and nothing else upset the apple cart. Very few people who’ve been in it for five, eight, 10 years have had very smooth rate increases.”

The number of people affected is relatively small compared to the population of California, Wood noted. Some 32 million residents will keep the coverage they have through their employers, Medicare, and the Medi-Cal public health program for the poor, he said, and millions more are uninsured and may be eligible for some type of support.

But consumer advocates say there’s more to the story, too. Canceled policyholders may lose their doctors and hospitals. That’s because some top California hospitals, including the University of California-Los Angeles and Cedars-Sinai medical centers, are not participating in most of the new health plans.

“How good is it to buy a policy in the exchange if you can’t go to UCLA?” Court asked. “That’s certainly not as good as it was in the old plans. … In some cases, I think people do get better policies. But in a lot of cases, like in California, they’re getting comparable policies. There’s very little different, except that their networks of doctors and hospitals are smaller, so that makes them worse or that makes them feel worse.”

Health industry consultant Bob Laszewski pointed out another problem with California’s apparent success story. Covered California has a goal of enrolling about 500,000 to 700,000 people receiving subsidies by April 1, 2014, the end of the open-enrollment period. But Laszewski notes that this includes the canceled policyholders.

“Why should we be so impressed with Covered California because they have signed up 80,000 people so far?” he wrote. “Or, even that their goal is to sign up 500,000 to 700,000 of the state’s 6.4 million people—half subsidy eligible—who are uninsured or having their insurance canceled?”

Wood said the canceled plans were not taken into consideration when California set its enrollment goals. The exchange hopes to enroll upwards of two million people by January 1, 2015. “We didn’t go back and re-project our number,” he said. “That did make our January [2014] number an easier target to hit.”

This post originally appeared on ProPublica, a Pacific Standard partner site.