The Trump administration has deported an undocumented North Carolina man who had been living in a church basement sanctuary space for nearly a year.

Samuel Oliver-Bruno, whose wife and son remain in the United States, was arrested the day after Thanksgiving, during what he was told would be a routine appointment with U.S. immigration authorities. At the meeting, he was being fingerprinted for what he anticipated would be an application to have his deportation deferred at a U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services office in Morrisville, North Carolina.

Plainclothes police at the office detained and escorted Oliver-Bruno to an Immigration and Customs Enforcement van behind the building. It appeared to witnesses that the ordeal had amounted to an attempt by ICE to weaponize Oliver-Bruno’s compliance with immigration authorities, using his meeting as a pretext to coax him out of sanctuary at the CityWell United Methodist Church so that he could be arrested. ICE has traditionally refrained from making arrests at places of worship.

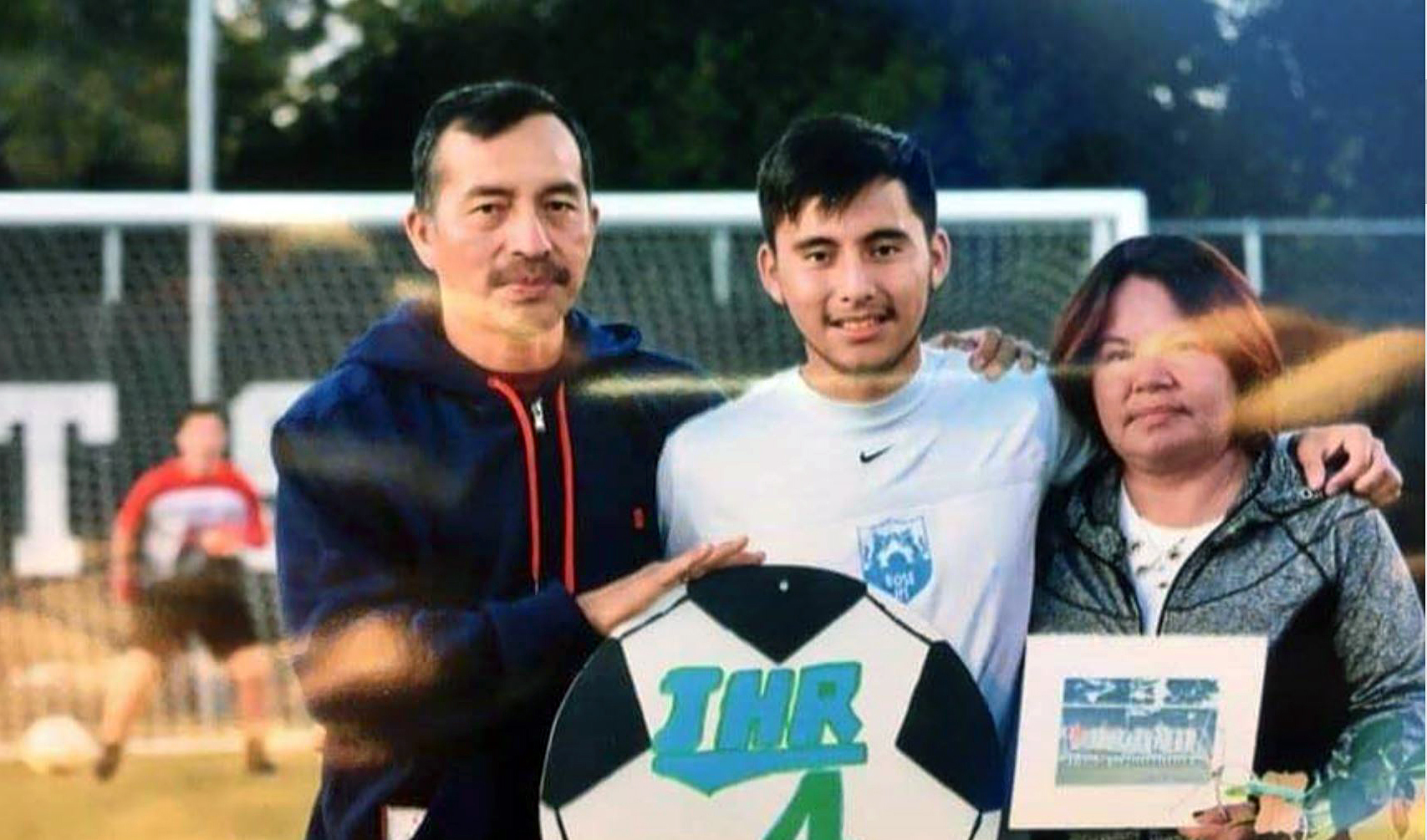

In a dramatic scene, members of the CityWell congregation, who had escorted Oliver-Bruno to his appointment, circled the van singing Christian songs and praying for about two hours before police arrested 27 of them. Oliver-Bruno’s 19-year-old son Daniel, was among those arrested; he has been charged with assaulting one of the ICE agents.

Oliver-Bruno pleaded guilty in 2014 to using false documents to re-enter the country after a journey outside of the U.S. In that instance, members of his congregation say he was panicked and struggling to return to his wife, who suffers from debilitating health complications.

“As a congregation, we are grieving and we are hoping. We are indignant, and we believe our nation can be better than what we are seeing right now,” says CityWell Pastor Cleve May. “We believe and bear witness to the love of God that does not stop at borders and does not exclude people on the basis of nationality, legal status, or any other man-made means of segregation. And we will continue to pursue any and every last possibility to reunite Samuel with his family.”

The congregation is gathering donations on its website to help Oliver-Bruno’s family with the cost of living and other considerations. The family’s legal representation is trying to determine if there is any way for Oliver-Bruno to return legally. “That’s an open question—it hasn’t been answered yet,” says Katherine Guerrero, a CityWell member who had coordinated Oliver-Bruno’s sanctuary on the church’s premises.

Guerrero underlined that Trump administration immigration enforcement detained Oliver-Bruno at a moment when he was risking his personal safety to comply with the law.

“What happened was that he was following an appointment that he had. [USCIS] made sure to tell us they couldn’t come to the church. He wanted a legal way to be here. He obviously didn’t want to continue living in the church after one year. The church had become a prison for him, and it’s just really sad that [had become] the case,” she says.

Oliver-Bruno’s arrest while complying with authorities sends a message to other undocumented people, both in and out of sanctuary, that compliance with authorities comes at a major cost, Guerrero says. “I don’t think if any of [the other people living in sanctuary in North Carolina] received a notice to get fingerprinted—I don’t think any of them would do it, obviously,” she says. Oliver-Bruno’s deportation “just makes it so that immigrants who are in the shadows continue to be in the shadows,” she adds.

And lawmakers seem to agree that ICE’s arrest at an immigration meeting sets a bad precedent for rule of law in the U.S.

(Photo: CityWell United Methodist Church)

“We believe the actions taken by ICE and USCIS in Mr. Oliver-Bruno’s apprehension are extremely concerning and deserving of scrutiny,” North Carolina Representatives G.K. Butterfield and David Price, both Democrats, said in a joint press release late last week.

“We will continue to speak out and fight against the unjust and cruel immigration policies of the Trump administration that are unnecessarily tearing families apart.”

USCIS declined to respond to comment specifically on Oliver-Bruno’s case, citing “pending litigation.” Pacific Standard then asked what litigation was pending in light of Oliver-Bruno’s completed deportation, but USCIS did not clarify.

On the topic of whether USCIS collaborates with ICE more broadly, Michael Bars, USCIS spokesman, wrote in an email that “the agency does not schedule an appointment at our Application Support Centers for an applicant who does not have a pending immigration benefit request. USCIS is committed to adjudicating all petitions, applications, and requests fairly, efficiently, and effectively on a case-by-case basis to determine if they meet all standards required under applicable law, policies, and regulations.”

ICE did not respond to Pacific Standard’s request for comment.

Oliver-Bruno’s deportation and concerns over how it might discourage U.S. residents from complying with authorities follow a series of immigrant enforcement arrests that raised questions over whether ICE was undermining the immigrants’ attempts to abide by the law. In July, ICE arrested an immigrant woman and her 16-year-old son at a courthouse, where they were preparing a domestic violence case against her ex-fiancé. That was but one of several such cases where immigration enforcement stands accused of undermining the governments’ efforts to get U.S. residents to comply with authorities over violent crime.

But for many, it remains unclear whether ICE is at all concerned with extending the rule of law to American immigrants. “I would definitely say that we have seen the cruelty of the immigration system firsthand,” CityWell’s Guerrero says.