If you were to look at Lisa Gherardini in just the right way, the Mona Lisa would jump out of the wall at you. But it wouldn’t come bursting out of the actual Italian countryside.

Gherardini was thought to have been the model for Leonardo da Vinci’s most famous masterpiece, which hangs in the Louvre. And if that’s true, then it follows that she must also have been the model for a similar painting on display at Madrid’s Museo Nacional Del Prado. Experts say La Gioconda, as Mona Lisa’s doppelgänger is called, was created by one of da Vinci’s pupils or followers as they painted aside their idol in the early 16th century. As revealed last year in the journal Perception, the two paintings are a stereo pair. They are two halves of a 3-D still, each depicting a perspective of the seated scene that’s approximately eyes-width apart, created half a millennium before Magic Eye books or Avatar.

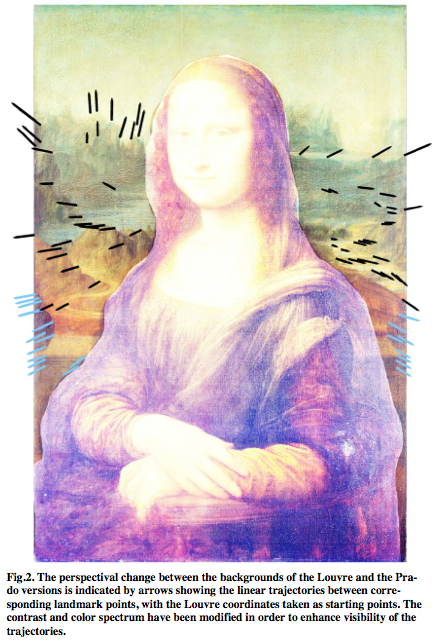

The background had long been blacked out in La Gioconda, but it was rediscovered and restored in recent years, helping to illuminate the vastness of the artistic homogeny. Even after restoration, though, the two backgrounds are not identical. And they’re not just different because of the varied painting styles: There’s a revealing mathematical consistency to most of the differences in their dimensions that appears to have exposed a da Vinci secret.

By measuring and analyzing landmark points in the backgrounds of the two paintings, a pair of German researchers has concluded that Gherardini didn’t have the actual North Italian countryside to her back as she posed. All those jagged hills in the background weren’t there at all—they were a Renaissance-era analog of a weather caster’s green screen. The hills were part of a motif, a mere representation of the countryside, one that may have been hanging in da Vinci’s studio.

“The backgrounds of the Prado and the Louvre versions are statistically not different with regards to shape, yet the background of the Prado version is zoomed in by a constant factor of 10% as compared to the background of the Louvre version,” the researchers write in a paper that will soon be published in the journal Leonardo.

The zooming, or expansion, is consistent throughout. If the background had been a true landscape, you would expect the expansion of nearer objects to be stronger than is the case for objects that seem further away. But that isn’t the case, suggesting that the differences were the product of the distances the artists were sitting from the motif as they painted.

(Photo: Leonardo)

“It was always speculated, but only speculated, that the landscape is a plane—not equipped with depth,” says Claus-Christian Carbon, head of the University of Bamberg’s general psychology and methodology department and a co-author of last year’s Perception paper and the upcoming Leonardo paper. “Indeed, it is plane, and we have found mathematic evidence for it.”