There is a family legend about Mookie Wilson and me. Aunt Nancy tells it best:

When you were two and a half years old, you told me, “When I’m big, and I’m black, I’m gonna be Mookie Wilson!” You weren’t too pleased when I informed you that no matter how big you might get, you were never going to be black, and never going to be Mookie Wilson.

In fact, you sobbed.

I do not remember this early blow to my professional aspirations. But I remember later things: Father-Son Day at Shea Stadium in 1989, when my pops and I walked the warning track waving a sheet that depicted two Ninja Turtles athwart the Mets’ insignia. I remember seeking third base each day of Little League, imitating the zip and glee that defined a Mookie Wilson three-bagger. I also remember my first baseball card of Mookie, where I learned he was not, in fact, as big as I had once imagined: 5’10”, 170 pounds. Topps regrettably did not have a statistical column for “love of the game.”

But, as Aunt Nancy promised, I did grow “big.” Taller than Mookie, in fact. Time works miracles, and we Mets fans nourish a well-documented faith in miracles. But my aunt was right on the other two scores: I remain not black, and I remain not Mookie Wilson. These are truths to which I long ago resigned myself.

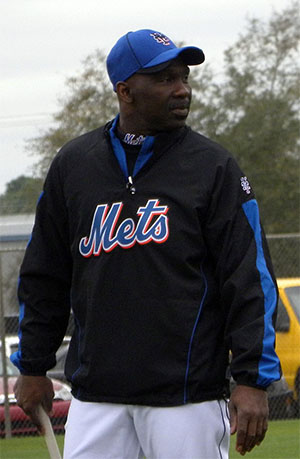

Wilson is, of course, best known for the ground ball that skipped through Bill Buckner’s legs and upended the 1986 World Series—but to many of us his career was a great deal more. Real Mookie fans followed him to the Toronto Blue Jays, and his coaching duties at various levels of the Mets organization. His new memoir, Mookie: Life, Baseball, and the ’86 Mets, is worth reading not least because it captures the man’s voice so well: honest, humble, self-deprecating, deeply committed to God and the game. (Wilson’s co-author is sportswriter Erik Sherman, whose editorial presence has the fine invisibility of Lonnie Wheeler’s in The Hank Aaron Story or even Ben Greenman’s work with Questlove.)

“Secret is, I don’t even remember stealing bases. I don’t because every time it was a challenge. It wasn’t about the number; just about outsmarting the pitcher and the catcher because they knew I’d be running.”

I called Wilson at his home in South Carolina to discuss life as a coach, the lost art of the triple, and a certain good friend of his.

What was the toughest part when you moved from playing to coaching?

It wasn’t a hard transition, really wasn’t. Um, the hardest thing is instead of now working on what you have to do, you have be very conscious of what the players around you are doing and try to evaluate them. Because you coach a lot of players who don’t have your same skill set. Find the powers they have, maximize that. That was the biggest challenge.

And how would you describe the Mookie skill set?

You know, the speedster that really needed to use his speed to be effective. Speedster on defense, too.

Your style of play is/was very old-school, small-ball, etc. Why has baseball moved away from all that?

I think that baseball has evolved. There’s still some players that have the abilities of slapping the ball, speeding around, but the game doesn’t require it any more. The game has moved in another direction. Ballparks are smaller. Teams want long-balls and guys with power. There’s still old-school players, but I don’t think you have scouts going out and looking for them. You’re not seeing a premium for speed. But I was just looking at the guy who’s leading the league in stolen bases, and there’s been a massive drop-off on that, so that’ll show you right there how the game has changed.

Even in 1986, there was something about that Mets team, something that felt old-school. Keith Hernandez—an intellectual of baseball—and you … did it feel like you were tapping into something elemental about the game in the ’80s?

Well, Darryl Strawberry was saying the other night that players are not as open to being themselves today. And then you lose a sense of having all these characters. We had so many characters on that team—characters with personality—and it was all about playing baseball. It wasn’t about promoting myself; it was about playing baseball. And where we are right now, guys are very conscious about having to promote themselves.

If you wanna talk about playing old-school, well, let’s say the players and their needs and obligations have evolved away from that. But yes, I would like to see the game kinda go back to some of the things we held to a higher value. I’d like to see the game go back to more of an emphasis on running and defense, instead of players complaining that the fence be too far, too deep. The bigger the field the better, I say. But we’re not gonna see that because of the economics and the culture of the game.

You were there for when ‘roids were getting real big, both at the end of your career and when you coached?

Oh yeah. You kinda saw it developing a little bit toward the end of my career but more later when I got into coaching, and you start to see that culture develop. And it’s a little depressing because I had such a passion for the game and enjoyment of the game; it wasn’t about “me me me,” it’s about what we can do as a collective team, and I think that is lost now a bit, because guys need contracts, and there’s nothing wrong with that, you gotta be a little selfish, but the team came first and that was most important. Their priorities toward the game are different now.

It’s about branding now, right?

Oh, that’s just a huge part of it. You have to really promote yourself. It’s worked out for a lot of guys, and it’s still a great game, obviously. No question, the best sport in the world.

Strawberry and Doc Gooden and Lenny Dykstra all helped define that era. Was it tough for you to see some of those guys fall off?

Matter of fact I was with Darryl and Doc the other night. And we have such a great relationship. And we were brothers, in that sense of the word—we were family. And when one falls on difficult times, it hurts. It hurts a lot, because you want to see the best for those guys. But, you know, that’s life, and sometimes we have to go through difficult times to be better people. But to answer your question, yes, it did hurt to see Doc and Straw and Lenny, when those things happened, those misfortunes, it affected all of us because we were one big happy family. Call it a cliché, but it’s true.

Who was the pitcher you were most scared of facing back in the day?

Oof, day-in, day-out, it was Nolan Ryan. Nolan Ryan was the guy I least wanted to face. No fun facing him—I’m glad I only had to face him every three months, when he was with the Astros. And then when I went to Toronto I had to face him again with the Rangers. Man. One thing about the Mets, we always had great arms. And on the Mets I think the one guy I wouldn’t want to face was Doc. I played behind him and I saw some of those fastballs and breaking balls, and ooh I wouldn’t wanna face Doc at all.

So Keith Hernandez has written the preface to your memoir. Regardless of tabloid stuff, he struck me as one of the most thoughtful ballplayers that I’ve watched. Curious what it was like to be in the dugout with him.

Keith is one of the most intelligent ballplayers I’ve ever had the joy of playing with. He breaks the game down—even when he’s with you in the dugout, he would be giving advice: This is what I’m gonna do, this is what this pitcher’s going to do, and this is what I’m going to do with that. On the field, yeah, he was our coach on the field. Positioning people when he had to. Always thought Keith would have been one of the greatest managers.

Why didn’t he take that road?

I don’t know, truly. I just think he enjoyed talking about the game, breaking it down, more than trying to coach it. I mean, that’s him. What he’s doing right now is what he excels at. I always thought baseball was missing out on the joy of having a great guy down there by the field, helping keep the product alive. He’s a lot of old school, man!

When did you decide to make yourself a switch hitter?

It wasn’t natural. I didn’t start switch hitting until my second year in triple-A ball. It’s not something that I had to do, but it happened by accident and I just picked it up very quickly—no real coaching. I enjoyed it, but if I had to do it over again I’m not sure if I would, but it kinda worked out for me.

You think it shaved off your batting average?

No question, I think that I probably woulda done a lot better, been a more disciplined hitter, because you don’t have the time to do the necessary work. Plus, it’s mainly right-handed pitchers, so you end up hitting left handed all the time. So the right-hand side ends up rusty. How many elite switch hitters can you think of? It’s not a thing any more. It’s not that easy, and I wouldn’t recommend it to any kid starting out.

You’re an artist of the triple, you held the Mets record for stolen bases—what is the secret to that Mookie dash?

Secret is, I don’t even remember stealing bases. I don’t because every time it was a challenge. It wasn’t about the number; just about outsmarting the pitcher and the catcher because they knew I’d be running. As for triples, if I hit one to the gap I was always thinking three, never thinking two. I just enjoyed running the bases.

Any particular catcher you especially liked to dupe?

I used to love toying with ’em, actually, so I really had fun with the whole thing. Tony Peña and I had this thing going on for years, and we still talk like kids about it; we really had a good thing going on. Guy I had the most fun with was Tony Peña.

When’s the last time you saw Bill Buckner in the flesh?

Two months ago. And I called him a week ago. We talk all the time. Bill and I are really good friends, we talk all kinda things: family, what we do, hobbies, and we talk baseball. I played minor-league ball with his brother in 1981. Bill is very easy to talk to—just a super guy. Once you get a chance to talk to him, you’ll see.