Robin Thicke’s summer hit “Blurred Lines” addresses what sounds like a grey area between consensual sex and assault. The images in this post place the song’s lyrics into a real-life context. They are from Project Unbreakable, an online photo essay exhibit that features women and men holding signs with sentences that their rapist said before, during, or after their assault. Let’s begin.

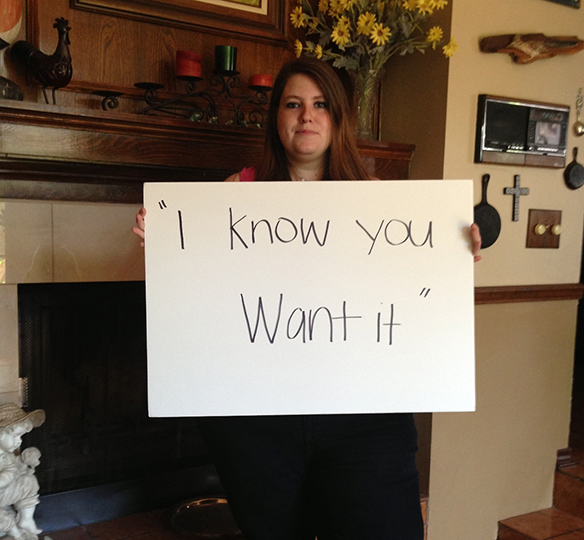

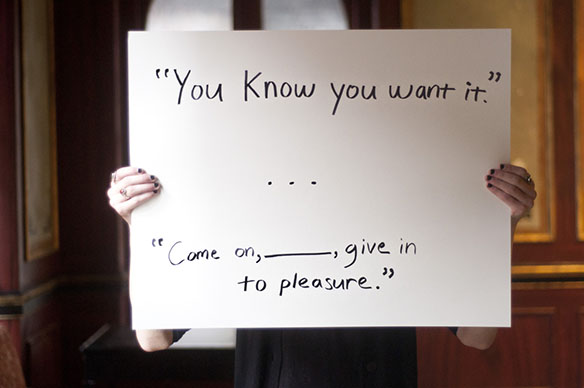

I know you want it.

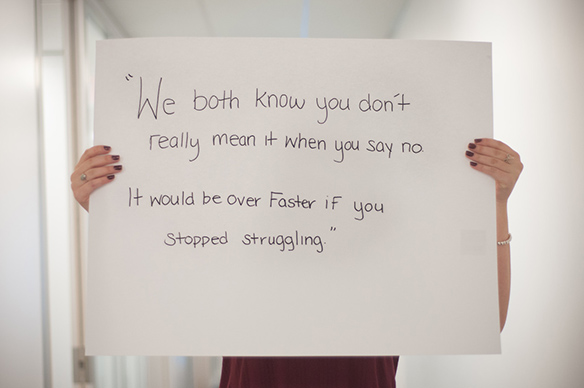

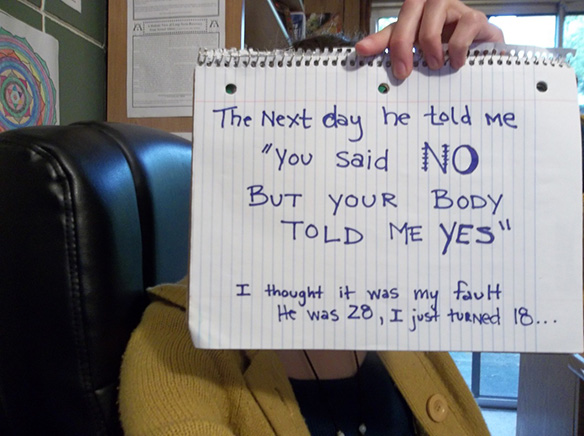

Thicke sings “I know you want it,” a phrase that many sexual assault survivors report their rapists saying to justify their actions, as demonstrated over and over in the Project Unbreakable testimonials.

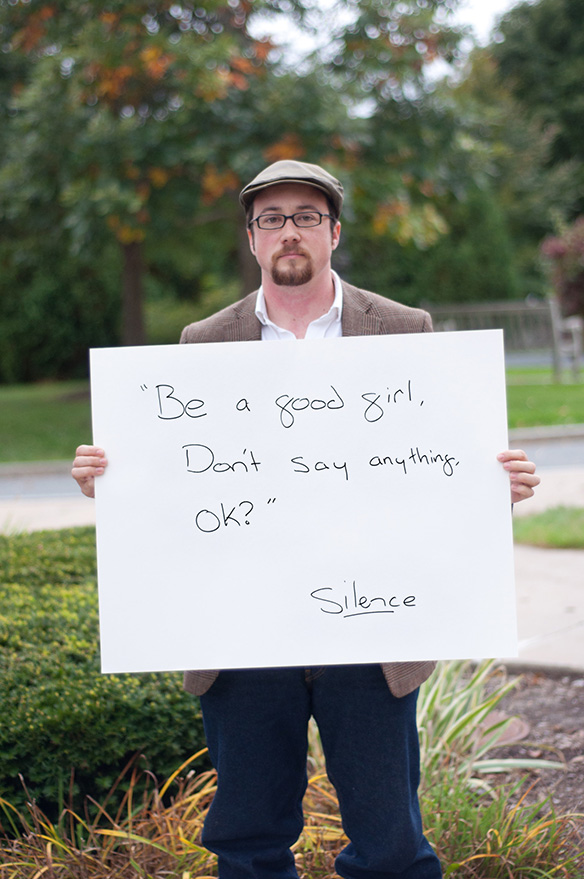

You’re a good girl.

Thicke further sings “You’re a good girl,” suggesting that a good girl won’t show her reciprocal desire (if it exists). This becomes further proof in his mind that she wants sex: for good girls, silence is consent and “no” really means “yes.”

Calling an adult a “good girl” in this context resonates with the the virgin/whore dichotomy. The implication in Blurred Lines is that because the woman is not responding to a man’s sexual advances, which of course are irresistible, she’s hiding her true sexual desire under a facade of disinterest. Thicke is singing about forcing a woman to perform both the good girl and bad girl roles in order to satisfy the man’s desires.

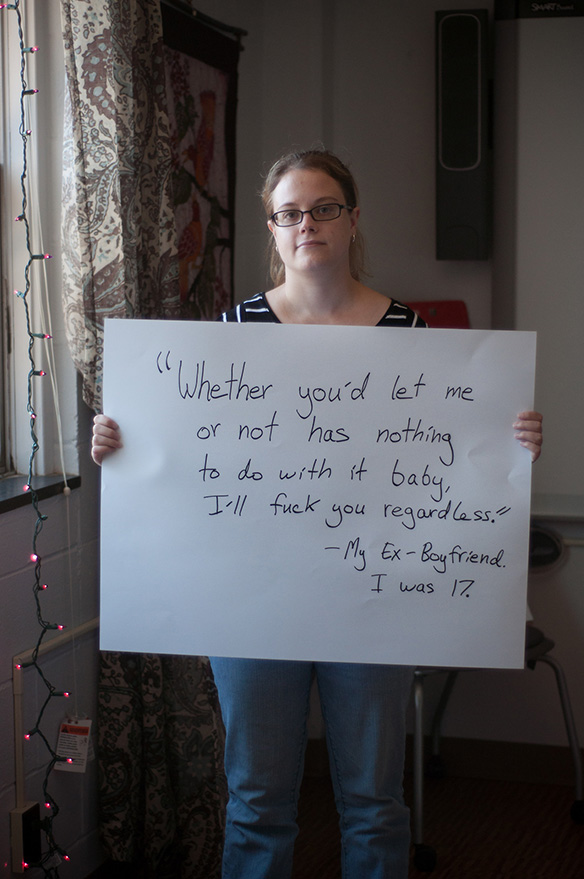

Thicke and company, as all-knowing patriarchs, will give her what he knows she wants (sex), even though she’s not actively consenting, and she may well be rejecting the man outright.

Do it like it hurt, do it like it hurt, what you don’t like work?

This lyric suggests that women are supposed to enjoy pain during sex or that pain is part of sex:

The woman’s desires play no part in this scenario—except insofar as he projects whatever he pleases onto her—another parallel to the act of rape: Sexual assault is generally not about sex, but rather about a physical and emotional demonstration of power.

The way you grab me.

Must wanna get nasty.

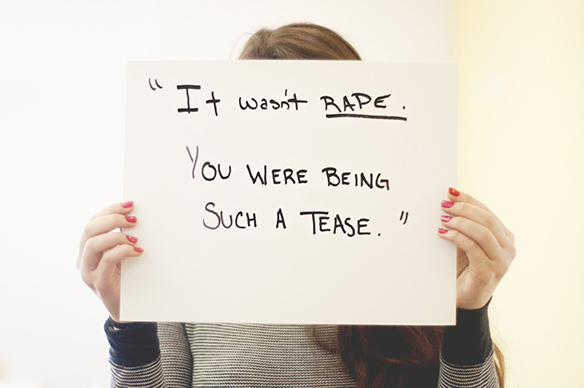

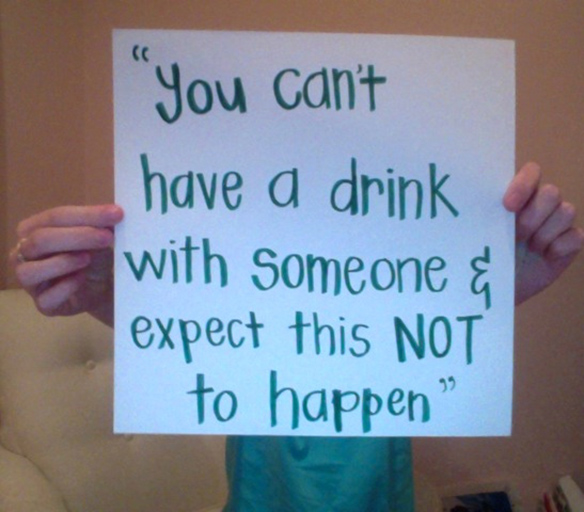

This is victim-blaming. Everybody knows that if a woman dances with a man it means she wants to sleep with him, right? And if she wears a short skirt or tight dress she’s asking for it, right? And if she even smiles at him it means she wants it, right? Wrong. A dance, an outfit, a smile—sexy or not—does not indicate consent. This idea, though, is pervasive and believed by rapists.

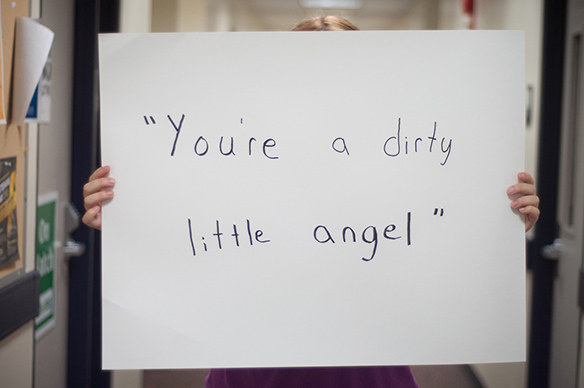

And women, according to Blurred Lines, want to be treated badly.

Nothing like your last guy, he too square for you.

He don’t smack your ass and pull your hair like that.

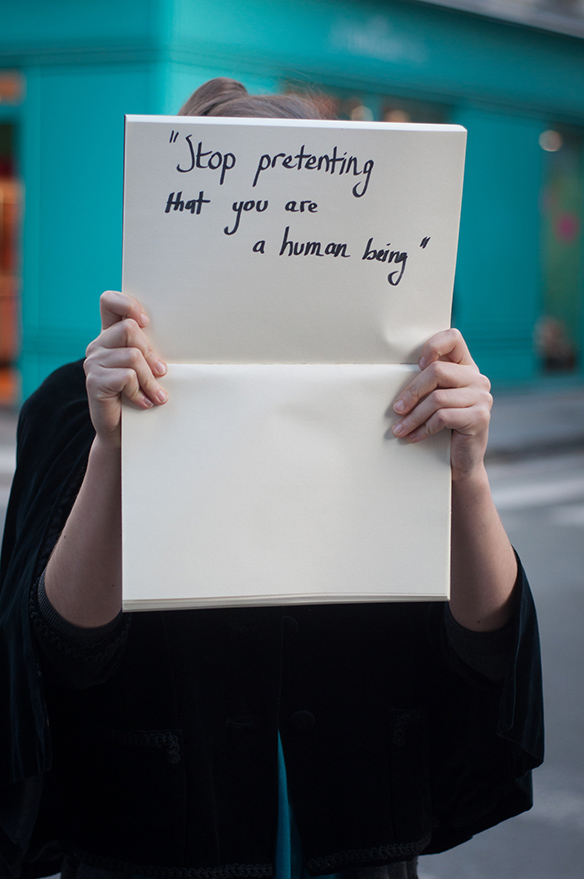

In this misogynistic fantasy, a woman doesn’t want a “square” who’ll treat her like a human being and with respect. She would rather be degraded and abused for a man’s gratification and amusement, like the women who dance around half naked humping dead animals in the music video.

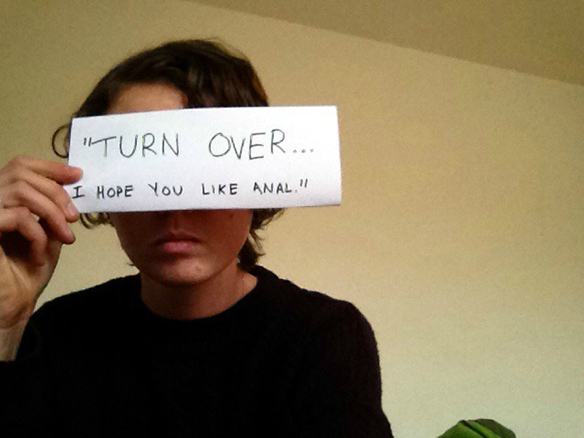

The piècede résistance of the non-censored version of Blurred Lines is this lyric:

I’ll give you something to tear your ass in two.

What better way to show a woman who’s in charge than violent, non-consensual sodomy?

Ultimately, Robin Thicke’s rape anthem is about male desire and male dominance over a woman’s personal sexual agency. The rigid definition of masculinity makes the man unable to accept the idea that sometimes his advances are not welcome. Thus, instead of treating a woman like a human being and respecting her subjectivity, she’s relegated to the role of living sex doll whose existence is naught but for the pleasure of a man.

In Melinda Hugh’s “Lame Lines” parody of Thicke’s song she sings, “You think I want it / I really don’t want it / Please get off it.” The Law Revue Girls‘ “Defined Lines” response to “Blurred Lines” notes, “Yeah we don’t want it / It’s chauvinistic / You’re such a bigot.” Rosalind Peters says in her one-woman retort: “Let’s clear up something mate / I’m here to have fun / I’m not here to get raped.”

There are no “blurred lines.” There is only one line: consent.

And the absence of consent is a crime.

This post originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site.