Drug use was never considered to be in a special category of human experience until we medicalized addiction—and that idea has been disastrous. Drugs are now returning to their life-sized status as part of the range of normal human behaviors. And they are ubiquitous. Realism about drugs and addiction must dictate drug policy.

HOW WE DISCOVERED, THEN REJECTED, ADDICTION

There is a myth that narcotics cause addiction, a myth created early in the 20th century. Yet both Americans and Brits used copious amounts of opiates in the 19th century—think laudanum, a tinctured opiate, given lavishly to infants and children—without any thought that they caused addiction.

How was it that people so familiar with the use of opiates were so unfamiliar with addiction to them? According to social historian Virginia Berridge, in Opium and the People, despite the liberal dosing of much of the British population with opium and then morphine, “There is little evidence that there were large numbers of morphine addicts in the late nineteenth century.”

But then, at the turn of the century, we made the brilliant discovery that narcotics caused a unique, irresistible, pathologic medical syndrome. As Berridge says: “Morphine use and the problem, as medically defined, of hypodermic self-administration were closely connected with the medical elaboration of a disease view of addiction.”

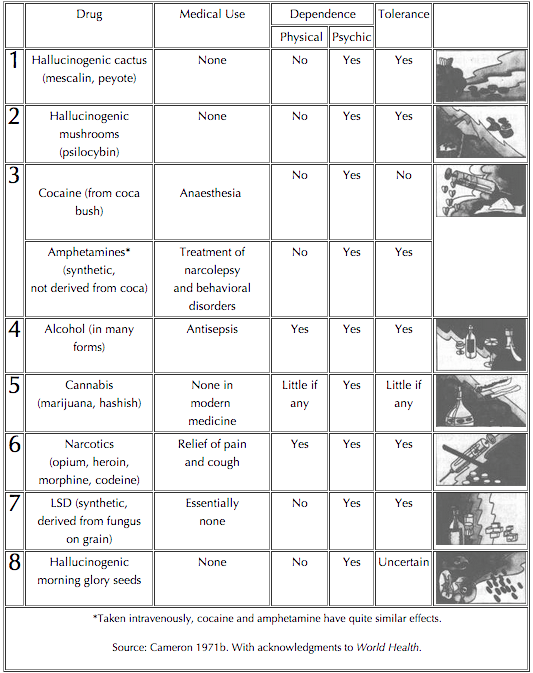

And so, by the 1960s, when many drugs burst on to the American scene, pharmacologists constructed lists of drugs and their dangers. These lists had two columns—drugs that cause addiction (or physical dependence), and those that merely cause psychological (“psychic”) dependence:

Only one class of drug was regarded by pharmacologists as truly addictive (aside from alcohol, which was categorized, and regarded, quite separately): narcotics. Nothing else produced physical dependence. So, after hundreds of years of the use of cocaine and marijuana, these experts were sure, neither was addictive. Nor did modern synthesized drugs, like amphetamines, have dangerous and addictive effects comparable to those of narcotics, they felt. And cigarettes are not even included in the table.

But today’s drug experts—like those who created the 2013 edition of psychiatry’s diagnostic manual, DSM-5—don’t think that way. There aren’t addictive drugs and drugs that cause psychological dependence. In fact, the DSM-5 doesn’t use the terms “addiction” and “dependence” at all when classifying substance use disorders (SUDs).

Instead, the DSM recognizes 10 classes of drugs: alcohol, caffeine, cannabis, two types of hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, stimulants (combining amphetamines and cocaine), tobacco, and an “other” category. All are divided into having “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe” categories of disorder.

And where did addiction, a term everyone knows, disappear to? Now no drug is notable as being “addictive.” Instead, any drug use may be more or less dysfunctional.

Addiction is no longer a specific property of drugs. Indeed, the DSM-5 uses the word “addiction” only in one place: “behavioral addictions.” And so far the DSM has found only one such addiction: compulsive gambling. Of course, American psychiatry is likely to find that more things are addictive. For starters, the DSM is pondering whether “persistent and recurrent use of Internet games, and a preoccupation with them” may constitute addiction.

What about food, sex, love, shopping? Doesn’t anyone get addicted to them, or to other things? Of course they do—and everyone not behind the DSM-5 knows it.

American pharmacology and psychiatry have backed themselves into a corner. In the old field of pharmacology, substances with widely divergent effects (heroin, LSD, marijuana, alcohol) were seen as so different that they were placed in different classes. But now in the DSM-5, since the concern is potential for misuse, all drugs are lumped together, with gambling et al. thrown in on top.

Pharmacology and psychiatry view any drug as being potentially harmful or addictive. But, in doing so, we are not having a pharmacological discussion.

REVERSING AMERICA’S BIOLOGICAL DEAD END

So we are emerging, begrudgingly, from misconceiving addiction.

Recognizing addiction outside the boundaries of pharmacology requires a monumental change in our thinking—even though it is merely a return to common usage from the 19th century and earlier, when “addiction” meant excessive devotion to something and was commonly applied across the range of human activities.

But modern American medicine is forced to arrive at this ancient position by a circuitous route. In 2013, in order to say gambling was addictive, the DSM-5 authors had to explain how gambling implicates—in the words of Charles O’Brien, head of that section—the same “brain and neurological reward system” as drugs. (But wait a second: Drugs aren’t called addictive in the DSM-5.)

As I indicate with Ilse Thompson in Recover!, to say that the brain responds to rewarding stimuli (think of sex, or watching a baby smile, or the taste of good food) is to state the obvious. But addiction doesn’t occur because things impact brain reward systems; it occurs in terms of people’s lived experience. The DSM’s characterization of substance disorders due to experienced problems is sensible, even obligatory—the only way we could go.

What is slowly dawning on pharmacology and psychiatry is that things aren’t addictive. As Ilse and I write, “Some people, at some point in their lives, for either shorter or longer periods, lose themselves in temporarily rewarding, powerful experiences, harming themselves.” This is addiction. And it doesn’t lead to lists of addictive and non-addictive stuff.

Deciding that gambling and other involvements can be addictive recognizes what Archie Brodsky and I wrote in Love and Addiction back in 1975:

If addiction is now known not to be primarily a matter of drug chemistry or body chemistry, and if we therefore have to broaden our conception of dependency-creating objects to include a wider range of drugs, then why stop with drugs? Why not look at the whole range of things, activities, and even people to which we can and do become addicted? We must, in fact, do this if addiction is to be made a viable concept once again.

HEROIN AND PAINKILLERS: A CASE IN POINT

That most heroin users don’t get addicted and that most heroin addicts quit their addictions and don’t die from heroin is so hard for people to stomach that these ideas must be presented gingerly. But these myths must be decisively refuted, since they underlie our crazy drug policy.

There is nothing about heroin that guarantees it will be more perpetually used than other substances, or engaged in more regularly than other activities. Comparing the lifetime use figures for heroin (2.6 percent) with current problematic users/addicts (0.1 percent) in the 2012 National Survey of Drug Use and Health, we find that four percent of those who have ever used heroin are currently addicted.

This percentage of those who currently have problems with or are addicted to heroin, versus the number who have used it, is far less than the comparable numbers for cigarettes and alcohol (which are included in the National Survey), and for love and potato chips (which are not). This is true even though only a very small percentage receive treatment.

The drop-off in heroin use/addiction is due both to the number of heroin users who don’t become addicted in the first place, and to those who quit their addictions (Norman Zinberg and Patrick Biernacki are two brave souls who first revealed these truths).

Most of us—fed by the media—still regard heroin as the paragon of addiction. But something is finally beginning to detract from heroin’s singular status.

Americans use a lot of painkillers, either because painkillers have always been popular throughout history, because Americans are especially frightened of pain, or because they are now so easy to obtain.

Most of us use painkillers reasonably, to address moments or periods of pain. But others do find them to be addictive; the elimination of pain is an appealing motivation.

And analgesic addiction has ceased being a tale about heroin—as much as the media and the public retain this view. As the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention informed us back in 2011:

Deaths from prescription painkillers (e.g., Vicodin, OxyContin) have reached epidemic levels in the past decade. The number of overdose deaths is now greater than those of deaths from heroin and cocaine combined….

Enough prescription painkillers were prescribed in 2010 to medicate every American adult around-the-clock for a month. Although most of these pills were prescribed for a medical purpose, many ended up in the hands of people who misused or abused them.

Although more men than women die due to painkillers, nonetheless, according to the CDC, painkillers currently kill more women than cervical cancer and homicide do. And, for every such death, 30 women end up in emergency rooms. Although heroin use and deaths are increasing—due to enhanced restrictions on narcotic painkillers—fatal prescription drug overdoses are still much more common than heroin deaths.

Ours is a 19th-century environment in terms of the accessibility of narcotic painkillers, only we use pills instead of laudanum and morphine. While it was once people who obtained the pills illicitly (per the CDC quote) who died from them, most deaths are now associated with filling multiple prescriptions, even though individually the prescriptions might be legitimately obtained.

Pharmaceuticals are more likely than heroin to lead to overdose deaths because they are more likely to be combined with other drugs, including alcohol. And it is such drug combinations that cause 90-plus percent of overdose deaths. So perpetually focusing on heroin overdoses, as the New York Times and other media do, simply takes our eye off the ball.

THE DRUG CORNUCOPIA FOR THE 21ST CENTURY

The situation with painkillers is a microcosm of drug use in America. Whatever their dangers, we’re not going to eliminate pharmaceutical painkillers, and no one says we should. They have a beneficial purpose that everyone appreciates.

We use many other drugs for similarly practical reasons. But sometimes their use leads to negative consequences. And someone has to tell America, “Deal with it!”

We must deal with drug use as a normal part of human experience, wrongly placed in some other category in the 20th and 21st centuries by political, legal, economic, and social forces. We can’t do without psychoactive drugs—and we seem less inclined to all the time—but we haven’t come to grips with what this says about us, about drugs, and about drug policy.

Despite our irrational fears, illicit substances are well on their way to being legalized, starting with marijuana here and in Latin America, and the decriminalization of all drugs in Portugal, among other developments around the world.

Meanwhile our use of legally available substances—like alcohol, tobacco, and coffee—has varied over time, but will not disappear and will always be substantial. (Do you think nicotine is more addictive than caffeine? I don’t.)

Let’s return to pharmaceuticals. We are a medicated society. The use of prescribed mind-altering substances (painkillers, antipsychotics, antidepressants)—is increasing exponentially, and at earlier ages. These drugs and others are commonly prescribed for kids for ADHD and bipolar disorder (the specialties of boys and male adolescents and girl adolescents respectively). Such drug use is a cornerstone of everyday American life.

The drugs prescribed to support our and our children’s mental health will only become more prevalent, judging by their skyrocketing use over the last three decades. In the case of pharmaceuticals, I (along with many others) think we are going overboard. Nonetheless, for better or worse, Americans must learn how to deal with these medications.

And then, there are performance enhancing drugs (PEDs). Who would endanger their health (as we are told these drugs do) in order to become sports heroes and to make multi-millions of dollars? Everyone from Ben Johnson, the Canadian Olympic gold medalist, to Lance Armstrong, to several top baseball stars—and those are only the ones who have been caught.

We may pretend that we can eliminate PEDs. But if they help top-flight athletes to excel and others to join their elite circle, they will always be popular. And PEDs are not just for world-class athletes—they are present wherever they are seen to improve people’s chances to get ahead in life, including kids in high school and college trying to achieve better grades with Adderall, Ritalin, etc.

CONCLUSIONS

America and the world have become an open drug marketplace. This was the case for most of human history, only people didn’t have the instant access to so many substances that they do now. Think, in this context, of the Internet—for which Silk Road is just the tip of the iceberg. This trend cannot be reversed. We must deal with it.

And how can we deal with it? Demonizing drugs that many people want to use—e.g., designer/club drugs, alcohol, heroin, LSD, PEDs—makes no sense, and is not an appropriate role for public health. All drugs should be legal, with appropriate controls (as with alcohol, including age, driving, places and times for purchase and consumption, and taxation) and medical supervision (prescriptions).

But, underlying any successful cultural coping strategy, people need to be raised with, and educated into, “substance intelligence”—that is, the self-awareness, knowledge of drugs, and skills for managing substance use. They won’t be able to function in the new world without such intelligence.

This is the 21st century on drugs.

This post originally appeared on Substance, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “We Need to Normalize Drug Use in Our Society—Deal With It!”