As New York slouched through the pre-Memorial Day workweek this year, a fissure appeared in the surveillance state.

Someone—a “supervillain,” “Braking Bad,” the “subway saboteur“—was yanking the emergency brakes on subway trains, disrupting many thousands of commutes. And, he’d been doing it continually for months—perhaps even years. Despite the MTA’s awareness and chagrin, he remained free and relatively unimpeded from meddling with more trains.

Many of the responses to reports of the brake-puller were predictably hostile. But amid quasi-joking calls for his beheading and jokes about him being Governor Andrew Cuomo (who controls the struggling subway system and has overseen its decline in service), an undercurrent of sympathy and celebration of the mischief maker gurgled through New York’s discourse streams. “WHY AM I ROOTING FOR THIS GUY??” an editor at The Nation wondered aloud. Across Twitter, the “supervillain” found stans, and was repeatedly called a hero.

Supporters sometimes explicitly characterized his actions—witting or not—as a protest against police surveillance. “Monkey-wrenching is an important part of anarchist praxis,” one reporter wrote. “His manifesto:” another person tweeted, “tell NYPD hands off immigrant delivery workers,” referring to the department’s practice of stopping food-delivery workers and seizing their e-bikes. In the face of rapidly increasing police surveillance, people were finding delight in a regular person who had successfully bucked the machine, at least for a few months.

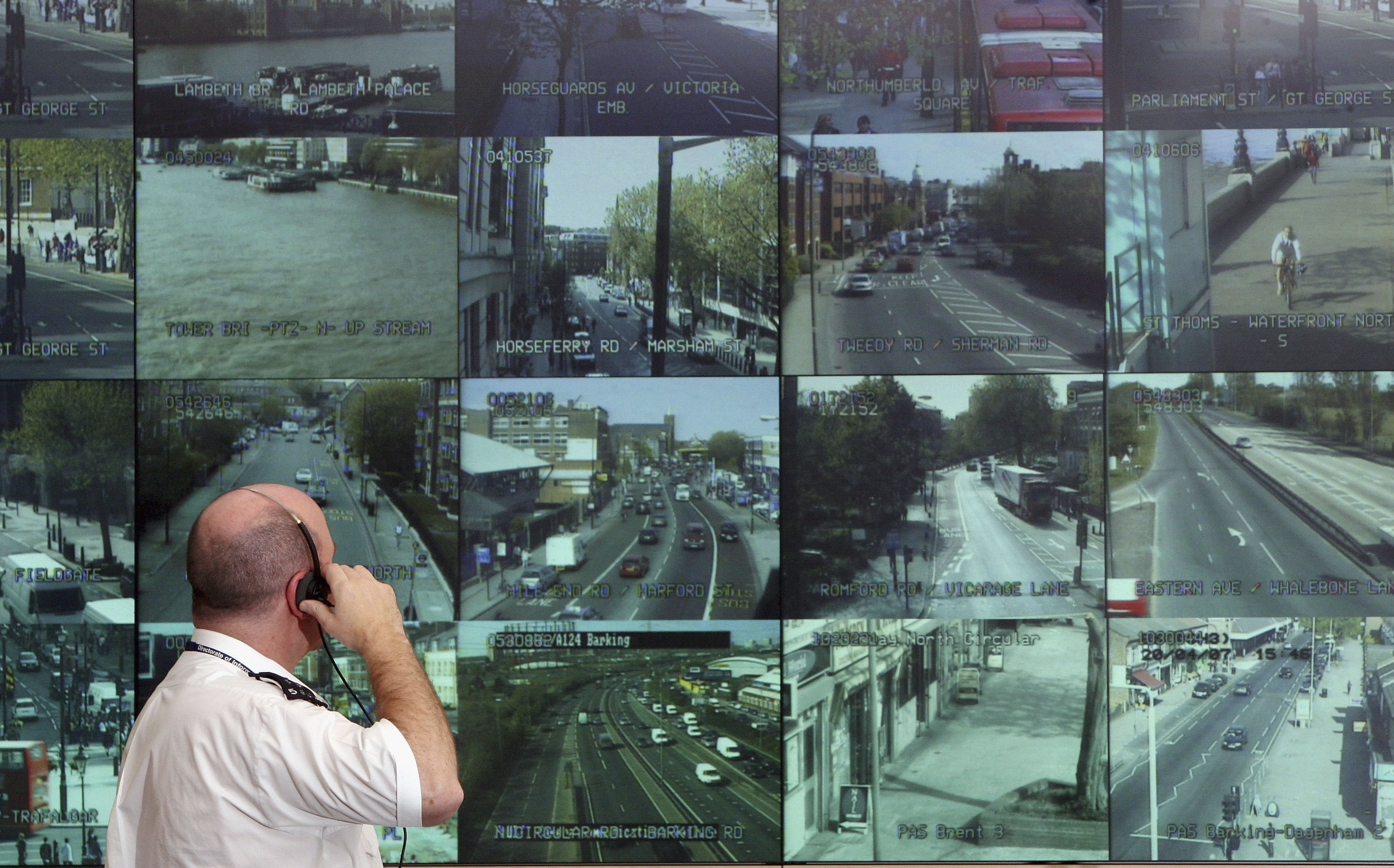

In some international cities, the average person is captured on camera an estimated 300 times a day, and most United States cities are not far behind. But if a rogue brakeman can repeatedly kneecap entire train lines for months without getting caught, then how much surveillance are our cities under, exactly?

Surveillance isn’t exactly new. Tailing individuals in person is about as old as policing itself. Wiretapping of individual telegraph lines goes back to the mid-19th century, and became a widespread police tool during Prohibition. But these old forms of surveillance required lots of manpower, and were annoying to carry out. “It used to be that police had to sit in their hot cars, drink cold coffees, and watch their suspect go from place to place in order to follow them,” says Andrew Ferguson, a law professor at the University of the District of Columbia and author of The Rise of Big Data Policing: Surveillance, Race, and the Future of Law Enforcement.

What Ferguson calls “big data policing” is a much more recent surveillance paradigm that has been developing since the 1990s—but especially over the last decade with the rise of predictive policing, camera ubiquity, facial-recognition technology, and sensor surveillance from Internet of Things devices that create data trails useful to police investigators. Fitbit data and recordings from “Alexa” speakers are already being used in criminal trials. Across the country, new technologies continue to appear in different ways, but one thing is true almost everywhere: People are being watched more than ever, with little oversight.

Surveillance cameras and license-plate readers became common in cities’ public spaces in the ’90s, but the technology was relatively new and spotty, says Bryce Clayton Newell, a surveillance scholar at the University of Oregon and editor at the journal Surveillance & Society. As city streets grew increasingly pockmarked with cameras, an activist group called the Surveillance Camera Players created camera maps of many major American and European cities in protest, showing routes that objectors could take to opt out of being filmed. “It’s becoming much more difficult to plan one of those sorts of routes,” Newell says.

This preemptive, eyes-everywhere approach is fundamentally changing policing. “This isn’t the same power balance we’ve had between law enforcement and the public,” Ferguson says. “We’re used to police collecting information when a crime has been committed in order to find the person who did it, but not this generalized monitoring of people because it might be useful later for crime investigation.”

Chicago, for example, has installed some 35,000 public surveillance cameras that police have access to. And although large cities, with their similarly sized police budgets, have the highest camera density, smaller municipalities are catching up. Rural areas are increasingly adopting police body cameras, license plate readers, and more. “One of the things that happens with technology is that it all gets cheaper and easier to acquire,” Ferguson says.

Three new surveillance technologies have gotten notably easier to acquire in recent years: police body cameras, predictive policing programs, and facial-recognition software. Body cameras were first deployed in the United Kingdom around 2006, and have been in use in the U.S. for about a decade, Newell says, but have become increasingly ubiquitous in the five years since police officer Darren Wilson shot Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. No footage of the shooting existed, and witness testimony disagreed on the facts; a nation searching for a quick solution to prevent this situation from happening again quickly embraced body cameras as a panacea for police accountability. Regulation of the cameras, however, has been scant, and always long after implementation.

For his research, Newell embedded in police departments during their adoption of body cameras. Initially, officers feared the accountability promised by the cameras. However, after a while, the officers began to see body cameras “as a tool to exonerate themselves, and to collect evidence, such as an admission of guilt or witness statement,” Newell says. “I think the sense is that the cameras haven’t brought the level of oversight that the officers feared at the beginning.”

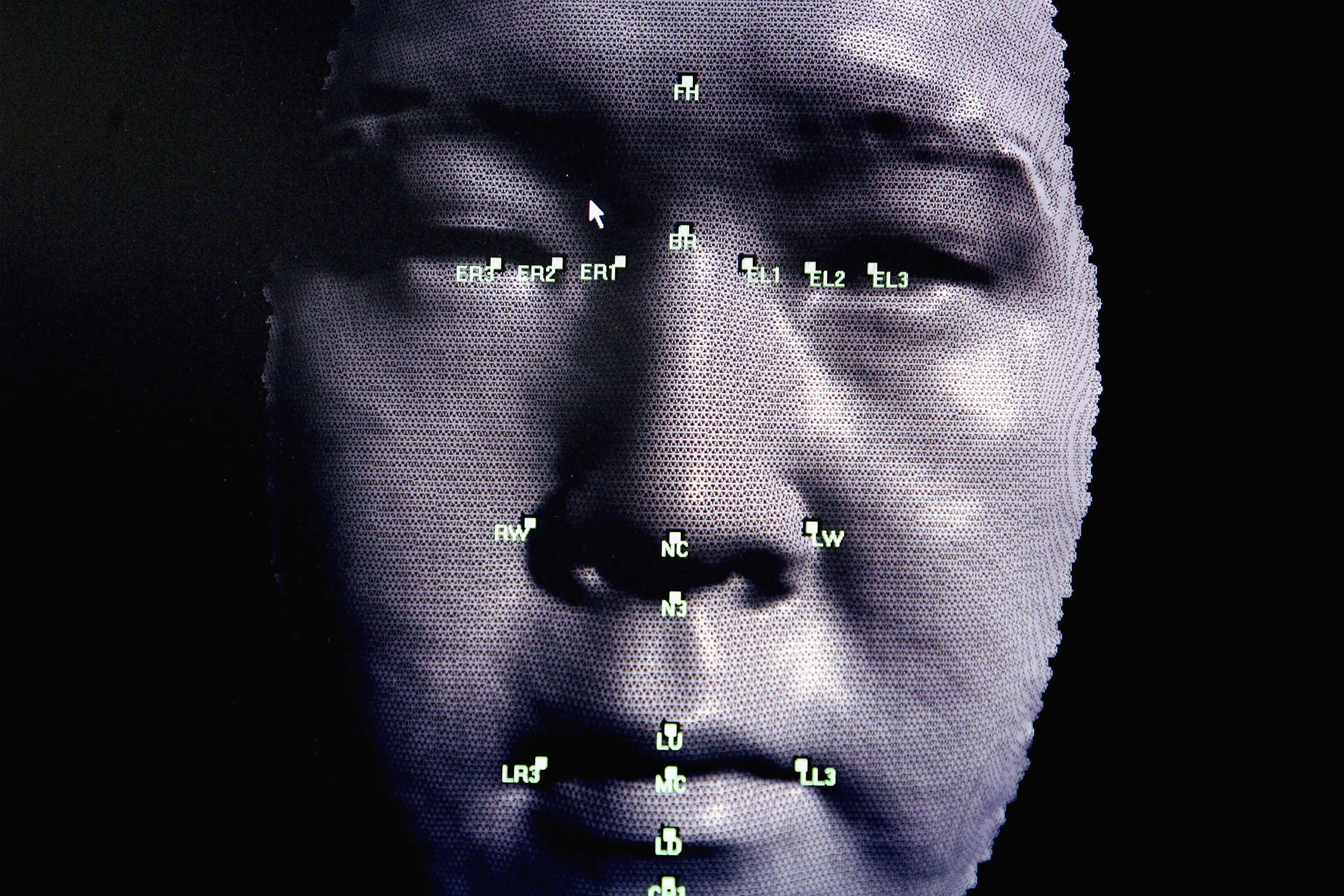

(Photo: Matt Cardy/Getty Images)

An Arizona State University study of the Mesa Police Department found that officers who wore body cameras issued more tickets than those who did not, “perhaps because they were concerned about being reprimanded for not issuing citations when the video evidence showed citizens violating an ordinance,” the researchers wrote. However, the study also found that officers wearing cameras conducted fewer stop-and-frisk searches. “Like us, police are also being monitored in new ways,” Ferguson says. “So this is an interesting workforce surveillance experiment going on with policing.”

By the end of 2016, nearly half of the U.S.’s police departments had body cameras, in part thanks to the Department of Justice’s distribution of over $20 million in grants for the technology. That number has continued to grow as the company formerly known as Taser (which rebranded itself as Axon in an effort to distance itself from the stun-gun weapons it still makes) began giving away cameras to departments for free—later charging lucrative, recurrent subscription fees for requisite storage of data and footage. As of 2016, Axon reportedly controlled at least three-quarters of the body camera market, and last year purchased its main competitor.*

Sophisticated predictive policing tools are also undergoing a widespread spike in adoption. These algorithmic programs synthesize massive amounts of data to identify people and locations most at risk for committing crimes, in order to allow police to deploy resources in a more targeted way. Such programs have faced strong criticism that their assumptions result in unfair targeting of black and latino communities; for example, in April, the Los Angeles Police Department was forced to end its LASER program for this reason, after community outcry and a lawsuit from the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition, which works to fight police oppression and dismantle government surveillance systems in L.A.

Because these intelligence programs require so much information on an entire population to make meaningful predictions, they also require perpetual surveillance regimes. “In order for [predictive policing programs] to work and do the social network analysis, they need to have constant streams of data coming in,” Ferguson says. “That ends up surveilling a lot of people who aren’t under suspicion as well.”

Even further along the Minority Report spectrum is facial-recognition technology, which finally developed enough that police departments are beginning to adopt its use for real-time scanning of video-feeds to match faces with those in a database. The Federal Bureau of Investigation and many local police departments already do a manual version of this, comparing pictures and video stills to national databases of government ID photos and mugshots that contain images of the majority of American adults, according to the Georgetown Law Center on Privacy & Technology.

But many experts warn that the available facial-recognition softwares, such as Amazon’s Rekognition, are still far too unreliable for police usage, especially at identifying darker faces. One police officer in a suburb of Portland, Oregon—reportedly the first to deploy Rekognition—ignored Amazon’s guidelines about “search-confidence percentages,” and set the system to always return five matches, no matter the likelihood. He also created a website that allowed officers to search from their cars, and “[t]o spice it up, he also added an unnecessary purple ‘scanning’ animation whenever a deputy uploaded a photo—a touch he said was inspired by cop shows like CSI,” the Washington Post reported.

In the past two years, Seattle and Oakland have passed local ordinances requiring the city council to approve the adoption of any new surveillance technologies, and, last month, San Francisco banned the use of facial-recognition technology. But almost everywhere else “there’s no one watching, police can just make things up as they go,” Ferguson says. “There are no rules.”

However, that might be changing. Perhaps because of its strong associations with dystopian science fiction, facial-recognition technology has become a flashpoint lately for discussions about police surveillance. Ferguson recently testified about the tech before the House Committee on Oversight and Reform, and said that, even as a professional surveillance Cassandra, he felt like a moderate in the room. “I was surprised by the bipartisan concern about this technology,” he says. “The conservative Republicans seemed as outraged as progressive Democrats that this technology was being used without any regulation.”

(Photo: Ian Waldie/Getty Images)

Irrespective of the concerns of our federal politicians (and, perhaps, their constituents), most cities continually build onto their surveillance state without having a conversation about whether its residents are OK with the architecture. “Whenever I give a talk, I always ask: How many of you know what surveillance technologies are being used in the community we’re in right now? Most people don’t know,” Ferguson says. “And where would they even go to find out? Even council members often have no idea of the technology being used.”

Instead of surveillance regulation by elected representatives, police technologies are primarily governed through what Newell calls “policy by procurement” (making policy simply by adopting a new, unregulated technology) and Ferguson’s idea of “policy by contract” (the stipulations on the usage of the technology and its data are determined only by the contract lawyers for the city and tech company). “There’s no overriding legislation or constitutional mandate that restricts their ability to use these technologies,” Newell says. “Our political and legal responses come after the fact.”

Legislation also isn’t always a check on surveillance. “Post 9/11, national security prerogatives and counterterrorism tactics were rapidly incorporated into domestic policing,” says Hamid Khan, an organizer for Stop LAPD Spying. Khan says that the 9/11 Commission Report, the Patriot Act, and the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act all created programs that brought “behavioral surveillance and data mining into the mix, and expanded the scope of intelligence gathering locally.”

These reports and legislation resulted in the country-wide creation of local Fusion Centers, which are “are repositories of all the information that is gathered from the military, the National Counterterrorism Center, private contractors, and local police,” Khan says. “At the heart of that program is the notion of behavioral surveillance.”

Despite all the ongoing privacy erosion, there’s not good evidence that much of the surveillance actually reduces crime or makes people safer. Research in the U.S. and the U.K. shows cameras’ effects to be at best unclear, and no better at deterring crime than less-intrusive techniques like increasing lighting. Beyond cameras though, many surveillance technologies haven’t really been studied at all, Ferguson says.

And the tools that are implemented often aren’t well-utilized, thanks to limited training and resources for equipment and software updates. When Newell was embedded with a department, “all the police officers were using laptops in their cars that ran Windows XP, and this was in 2014, 2016,” he says. Other officers told him that their license plate readers got so many false matches, that they stopped trusting them at all.

The NYPD did eventually catch the subway brake-puller. But it was only able to identify him thanks to a cell phone picture submitted by a bystander. All that government watching—but to what end?

*Update—June 10th, 2019: This article has been updated.