Florida will likely pass what many call an “anti-sanctuary” bill this week: The bill, bitterly battled over in the state’s legislature, will make it illegal for Florida police officers not to cooperate with with Immigration and Customs Enforcement and will inflict penalties—including removal from office—on any officials who enacts sanctuary-city policies.

With Florida poised to become the latest state to enact a state-wide legislation on sanctuary policies, we set out to make a map of states that have similar anti-sanctuary laws, as well as states that have declared themselves “sanctuaries.”

It proved harder than you might think. While the notion of “sanctuary”—sanctuary cities, sanctuary counties, sanctuary states—appears in the news frequently, there’s no legal definition of, or widespread agreement on, what qualifies as one. And there’s a lot of misinformation out there about what sanctuary policies do.

There’s less disagreement about qualifies as an anti-sanctuary policy: Like Florida, a collection of other states have laws where local authorities’ full cooperation with ICE agents is mandatory, making it illegal for any city or country to enact sanctuary policies. That makes a map of anti-sanctuary policies easier to make:

If and when Florida’s proposed new law goes into effect, 20 percent of states will have anti-sanctuary policies.

The anti-sanctuary movement at the state level began in 2009, largely as backlash to a pro-sanctuary movement that began at the city level in the late 1980s and ticked back up in the 2000s during an upswing in illegal immigration.

Disagreement About How Many Sanctuary States Exist

Depending on who you ask, the United States could have over a dozen sanctuary states or as few as zero. It all comes down to what the person answering considers to constitute as a sanctuary policy.

According to the Center for Immigration Studies, one of the most prominent anti-immigration advocacy organizations in the country, there are eight states that count as “sanctuary jurisdictions” as of April of 2019.

“My working definition of a sanctuary is a jurisdiction that has an ordinance, or an executive order, or a policy, or even an articulable practice of interfering with ICE’s efforts to remove their charges,” says Jessica Vaughn, CIS’s director of policy studies who helped create the organization’s list of sanctuary jurisdictions.

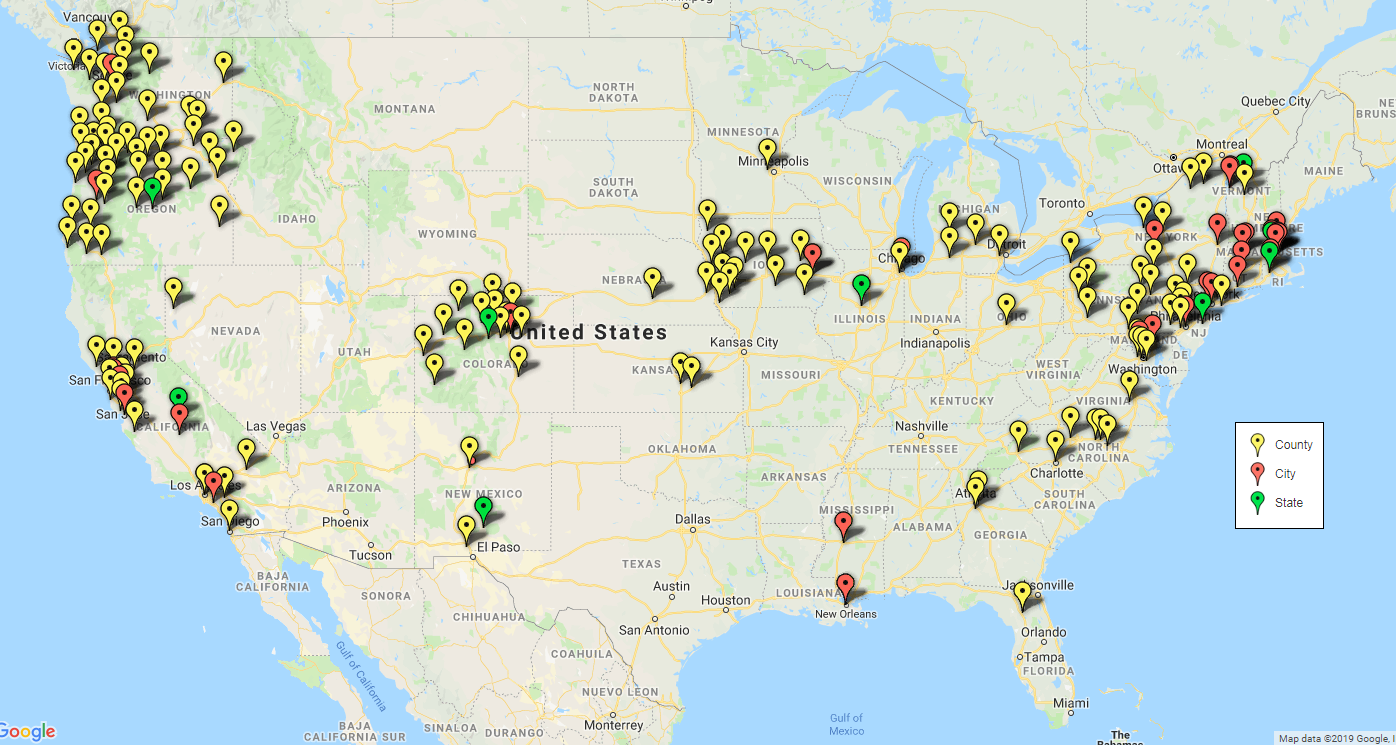

CIS’s map of these jurisdictions (states, counties, and cities) is frequently cited by newspapers and magazine reporting on sanctuary policies. Here’s what it looks like:

Other organizations and experts disagree with CIS’s list.

“According to how we define [sanctuary], California might be the only one,” says Krsna Avila, an immigrants’ rights fellow at the Immigrant Legal Resource Center, a pro-immigration research and advocacy group.

The ILRC has its own map, which uses a gradient of sanctuary-ness, rating the degree to which local jurisdictions cooperate with ICE. Here’s what its map looks like:

Understanding What ‘Sanctuary’ Means

Some people—often influenced by alarmist rhetoric from anti-immigration politicians—believe that sanctuary jurisdictions are places where undocumented immigrants are free from deportation or arrest. No such place exists anywhere in the U.S. There’s no state, town, or even city block where ICE agents cannot arrest an undocumented person: Even in San Francisco, the first city to declare itself a “sanctuary city” in 1989—which sits in the middle of California, which declared itself a sanctuary state in 2017—ICE arrested over 150 people in just one week in 2018.

So what, then, does “sanctuary” mean?

Living in the country as an undocumented immigrant is a civil offense, not a crime: That means that it’s not up to police—state, county, or city cops—to enforce immigration laws. That job is left to federal agents: namely ICE. However, ICE agents can’t be everywhere at once, so they often request that local law enforcement agents help them carry out their mandate. This happens in a variety of ways: ICE might ask police to let their agents interview someone in jail, deputize police officers to make immigration-related arrests, or request that police hold someone in jail until ICE agents can come arrest them.

Sanctuary policies seek to limit the degree to which local police work with ICE. For instance in California, one of the country’s strongest sanctuary jurisdictions, it’s illegal for state and local law enforcement to use any funds or resources to “investigate, interrogate, detain, detect, or arrest persons for immigration enforcement purposes.”

That does not mean that California police do not cooperate with ICE: Federal law mandates that when police arrest someone anywhere in the country—including all sanctuary states and cities—they send that person’s fingerprints and other information to the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees ICE. ICE can also procure warrants that compel local police officers to detain suspects wanted by the federal government.

Multiple courts have ruled, however, that local jurisdictions have the discretion to deny certain requests ICE makes. According to Avila and ILRC, there are six discretionary areas wherein local jurisdictions can choose not to cooperate with ICE:

- Local jurisdictions can decline what are called “detainer requests,” wherein ICE requests a local jail hold someone even after they should’ve been released so that ICE agents can come re-arrest them.

- They can decline to notify ICE when a person ICE is targeting is going to be released from jail.

- They can refuse what’s called a 287(g) contract, which allows ICE to deputize local law enforcement to make immigration-related arrests.

- They can refuse to provide ICE the use of a jurisdiction’s existing detention facilities.

- They can instruct police never to ask about a person’s immigration status.

- They can refuse to grant ICE agents access to jails to interview suspects if the ICE agents do not have a warrant.

Putting That All on a Map

The question of what states count as sanctuaries then comes down to a matter of degrees: How many different types of ICE requests must a state refuse for us to consider that state a sanctuary state?

For Vaughn and CIS, the most important thing toward deciding whether or not a state is sanctuary is whether or not it honors detainer requests. “A detainer is the primary tool used by ICE to gain custody of criminal aliens for deportation,” CIS’s sanctuary map explainer says.

That’s why CIS includes Colorado and New Mexico on its map, even though neither state has a law or executive order creating anything close to a sanctuary policy. However, essentially every county jail in both those states will decline ICE detainer requests. This is because civil rights groups brought lawsuits in Colorado and New Mexico in 2014 that questioned the constitutionality of detainer requests. In the Colorado suit, a district judge ruled in 2018 that a sheriff could not legally keep someone in jail after a judge had ordered that person released (or if the police otherwise had no reason to hold them other than a detainer request). A judge in New Mexico went even further, and ruled that local law enforcement is limited in information they can share with ICE. As such, almost all the sheriffs managing county jails in both states decided that, in order to limit legal liability and vulnerability to similar suits, they would refuse ICE detainer requests that came without warrants.

CIS includes Massachusetts for a similar reason: In 2017, the state’s Supreme Court ruled that detainer requests are unconstitutional, equating them to arbitrary detention.

The list of states that have actually passed sanctuary-like laws is short: California, Connecticut, Illinois, Oregon, and Vermont. Additionally, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Washington State are all currently under executive orders that limit the degree to which local law enforcement cooperates with ICE.

However, having laws or executive orders creating sanctuary policies might not be enough for a state be considered a sanctuary if law enforcement can still cooperate with ICE in significant ways.

“Some jurisdictions that call themselves sanctuaries don’t meet that definition, because they’re doing it as a sort of posturing—’Oh, we’re a welcoming city, we’re a sanctuary—but they actually do cooperate with ICE,” Vaughn says.

For instance, CIS does not consider Connecticut a sanctuary state, even though the state passed a law limiting cooperation with ICE in 2013. Connecticut still communicates and cooperates enough with ICE that CIS doesn’t count it as a sanctuary.

That gets us to our own map. Here it is:

To make our list of sanctuary states, we decided that only three states have laws on the books that have significantly limited cooperation with ICE: California, Oregon, and Vermont. On our map, we consider these the truest sanctuary states.

Next, we considered states that have sanctuary-like policies or executive orders in place that limit cooperation with ICE, but not to the same degree as the states we consider sanctuaries. These states, with limited sanctuary, are Connecticut, Illinois, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Washington.

Finally, we mark the three states that have court decisions somehow motivating or compelling local jurisdictions not to honor detainer requests: Colorado, Massachusetts, and New Mexico.