Doctors have long disputed that the payments they receive from pharmaceutical companies have any relationship to how they prescribe drugs.

There’s been little evidence to settle the matter—until now.

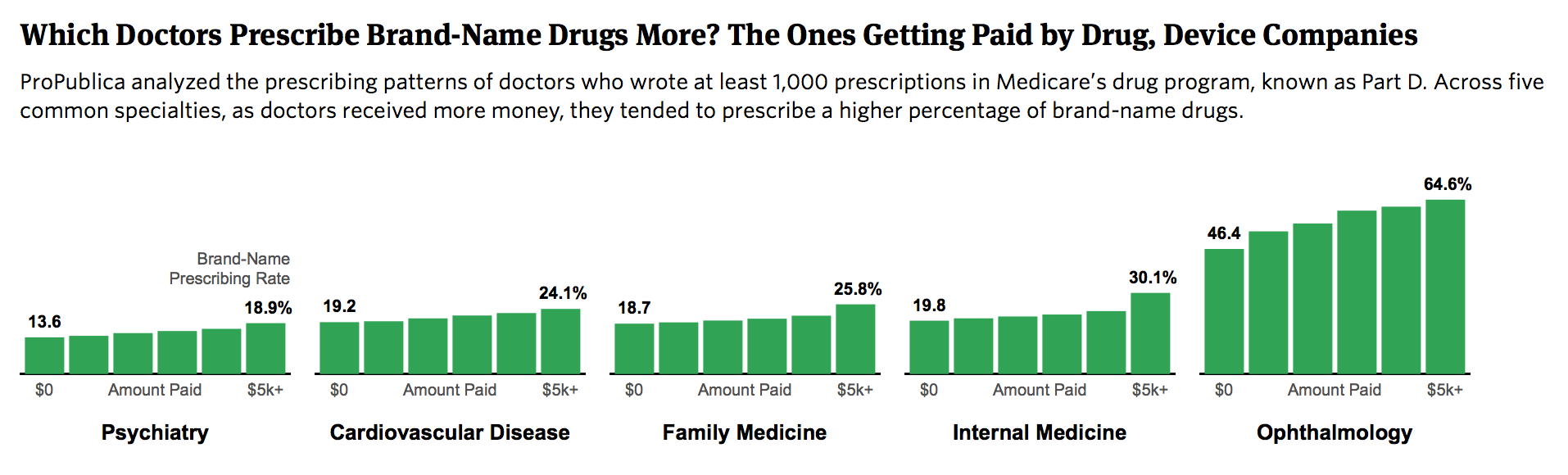

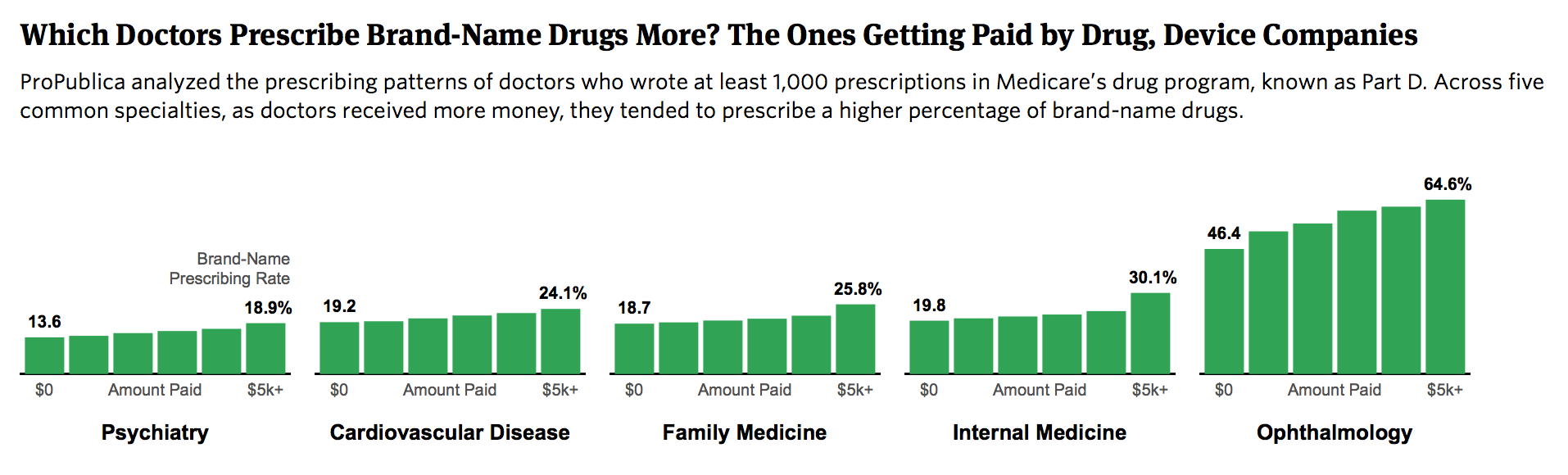

A ProPublica analysis has found for the first time that doctors who receive payments from the medical industry do indeed tend to prescribe drugs differently than their colleagues who don’t. And the more money they receive, on average, the more brand-name medications they prescribe.

We matched records on payments from pharmaceutical and medical device makers in 2014 with corresponding data on doctors’ medication choices in Medicare’s prescription drug program.

Doctors who got money from drug and device makers—even just a meal—prescribed a higher percentage of brand-name drugs overall than doctors who didn’t, our analysis showed. Indeed, doctors who received industry payments were two to three times as likely to prescribe brand-name drugs at exceptionally high rates as others in their specialty.

Doctors who received more than $5,000 from companies in 2014 typically had the highest brand-name prescribing percentages. Among internists who received no payments, for example, the average brand-name prescribing rate was about 20 percent, compared to about 30 percent for those who received more than $5,000.

ProPublica’s analysis doesn’t prove industry payments sway doctors to prescribe particular drugs, or even a particular company’s drugs. Rather, it shows that payments are associated with an approach to prescribing that, writ large, benefits drug companies’ bottom line.

“It again confirms the prevailing wisdom … that there is a relationship between payments and brand-name prescribing,” said Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard University Medical School who provided guidance on early versions of ProPublica’s analysis. “This feeds into the ongoing conversation about the propriety of these sorts of relationships. Hopefully we’re getting past the point where people will say, ‘Oh, there’s no evidence that these relationships change physicians’ prescribing practices.'”

Numerous studies show that generics, which must meet rigid Food and Drug Administration standards, work as well as name brands for most patients. Brand-name drugs typically cost more than generics and are more heavily advertised. Although some medications do not have exact generic versions, there usually is a similar one in the same category. In addition, when it comes to patient satisfaction, there isn’t much difference between brands and generics, according to data collected by the website Iodine, which is building a repository of user reviews on drugs.

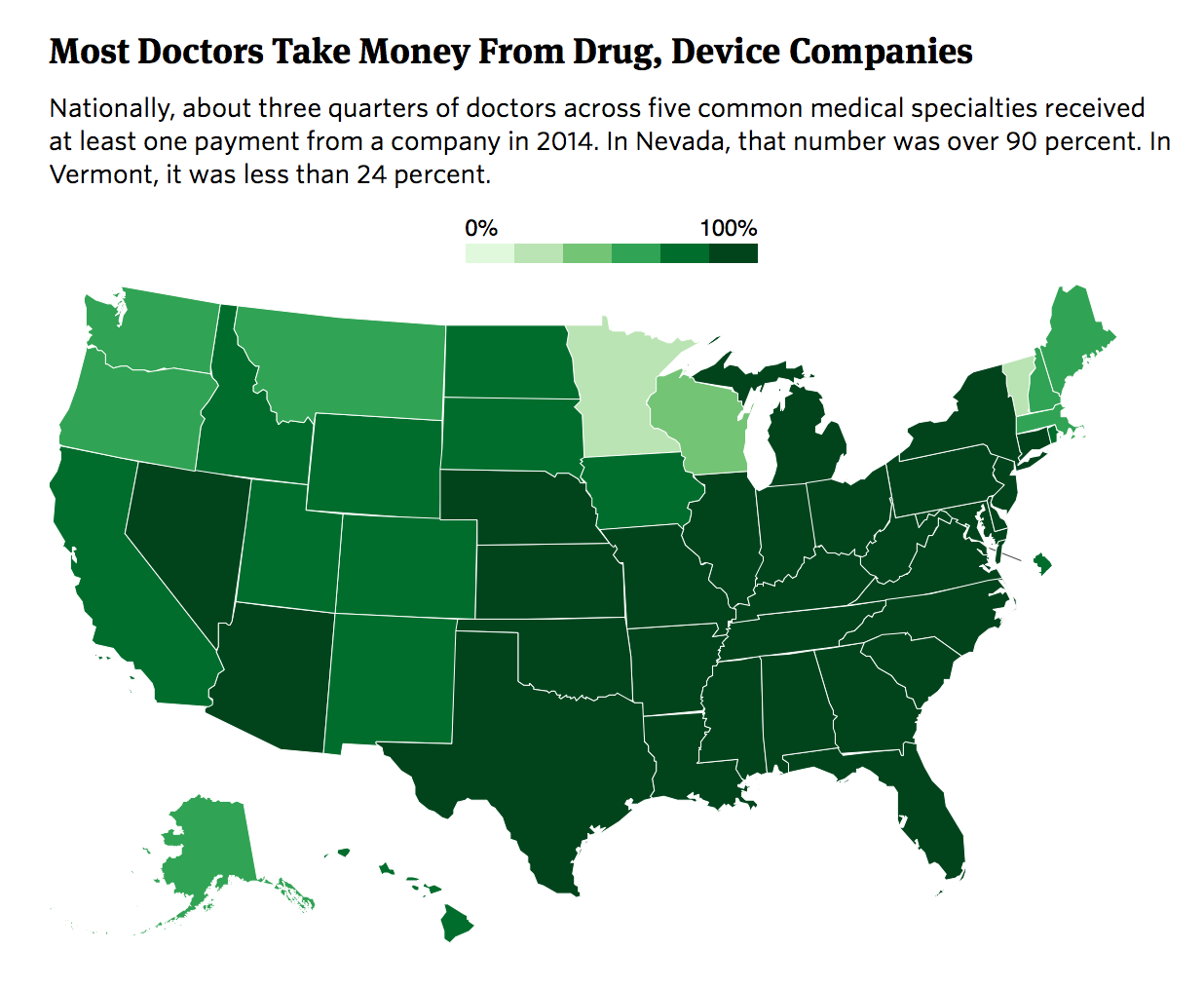

There’s wide variation from state to state when it comes to the proportion of prescribers who take industry money, our analysis found. The rate in Nevada, Alabama, Kentucky, and South Carolina was twice as high as in Vermont, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Maine.

But, overall, payments are widespread. Nationwide, nearly nine in 10 cardiologists who wrote at least 1,000 prescriptions for Medicare patients received payments from a drug or device company in 2014, while seven in 10 internists and family practitioners did.

Dr. Walid Gellad, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh and co-director of its Center for Pharmaceutical Policy and Prescribing, who also reviewed our analysis, said the pervasiveness of payments is noteworthy. “You can debate if these payments are good or bad, or neither, but what isn’t debatable is that they permeate the profession.”

The results make sense, said Dr. Richard Baron, president and chief executive of the American Board of Internal Medicine. Doctors nowadays almost have to go out of their way to avoid taking payments from companies, according to Baron. And those who do probably have greater skepticism about the value of brand-name medications. Conversely, doctors have to work to cultivate deep ties with companies—those worth more than $5,000 a year—and such doctors probably have a greater receptiveness to brand-name drugs, he said.

“You have the people who are going out of their way to avoid this and you’ve got people who are, I’ll say, pretty committed and engaged to creating relationships with pharma,” Baron said. “If you are out there advocating for something, you are more likely to believe in it yourself and not to disbelieve it.”

Physicians consider many factors when choosing which medications to prescribe. Some treat patients for whom few generics are available. A case in point is doctors who care for patients with HIV/AIDS. Others specialize in patients with complicated conditions who have tried generic drugs without success.

Holly Campbell, a spokeswoman for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the industry trade group, said in a statement that many factors affect doctors’ prescribing decisions. A 2011 survey commissioned by the industry found that more than nine in 10 physicians felt that a “great deal of their prescribing was influenced by their clinical knowledge and experience,” Campbell said in a written statement.

“Working together, biopharmaceutical companies and physicians can improve patient care, make better use of today’s medicines and foster the development of tomorrow’s cures,” she wrote. “Physicians provide real-world insights and valuable feedback and advice to inform companies about their medicines to improve patient care.”

Several doctors who received large payments from industry and had above-average prescribing rates of brand-name drugs said they are acting in patients’ best interest.

“I do prefer certain drugs over the others based on the quality of the medication and also the benefits that the patients are going to get,” said Dr. Amer Syed of Jersey City, New Jersey, who received more than $66,800 from companies in 2014 and whose brand-name prescribing rate was more than twice the mean of his peers in internal medicine. “My whole vision of practice is to keep the patients out of the hospital.”

Dr. Felix Tarm, of Wichita, Kansas, likewise prescribed more than twice the rate of brand-name drugs than internal medicine doctors nationally. Tarm, who is in his 70s, said he’s on the verge of retiring and doesn’t draw a salary from his medical practice, instead subsidizing it with the money he receives from drug companies. He said he doesn’t own a pharmacy, a laboratory, or an X-ray machine, all ways in which other doctors increase their incomes.

“I generally prescribe on the basis of what I think is the best drug,” said Tarm, who received $11,700 in payments in 2014. “If the doctor is susceptible to being bought out by a pharmaceutical company, he can just as easily be bought out by other factors.”

A third doctor, psychiatrist Alexander Pinkusovich of Brooklyn, also prescribed a much higher proportion of brand-name drugs than his peers in 2014 while receiving more than $53,400 from drug companies. He threatened to call the district attorney if a reporter called again. “Why are you doing a fishing expedition?” he asked. “You know that I didn’t do anything illegal, so good luck.”

ProPublica has been tracking drug company payments to doctors since 2010 through a project known as Dollars for Docs. Our first look-up tool included only seven companies, most of which were required to report their payments publicly as a condition of legal settlements. The tool now covers every drug and device company, thanks to the Physician Payment Sunshine Act, a part of the 2010 Affordable Care Act. The law required all drug and device companies to publicly report their payments. The first reports became public in 2014, covering the last five months of 2013; 2014 payments were released last year.

The payments in our analysis include promotional speaking, consulting, business travel, meals, royalties, and gifts, among others. We did not include research payments, although those are reported in the government’s database of industry spending, which it calls Open Payments.

Separately, ProPublica has tracked patterns in Medicare’s prescription drug program, known as Part D, which covers more than 39 million people. Medicare pays for at least one in four prescriptions dispensed in the country.

This analysis matches the two data sets, looking at doctors in five large medical specialties: family medicine, internal medicine, cardiology, psychiatry, and ophthalmology. We only looked at doctors who wrote at least 1,000 prescriptions in Medicare Part D.

Senator Charles Grassley (R-Iowa), who pushed for the Physician Payment Sunshine Act, said in a statement that “it’s gratifying to see” ProPublica’s analysis.

“Since brand name drugs generally cost more than generic drugs, what doctors prescribe has major effects on Medicare and other payers in the health-care system,” he said. “I look forward to more data, more analysis, and to hearing from doctors about what influences their decision to prescribe brand name drugs versus generic drugs.”

Dr. David W. Parke II, chief executive of the American Academy of Ophthalmology, suggested that many payments made to ophthalmologists don’t relate to drugs they prescribe in Medicare Part D, and instead may be related to drugs administered in doctors’ offices or devices and implants used in eye procedures. As a result, he said, it may be unfair to presume that industry payments are associated with prescribing in Part D.

Still, he said, ProPublica’s analysis points to areas that specialty societies may want to look at. “In some cases, there are very appropriate and clinically valid reasons” for doctors who are outliers in their prescribing. “For others, education may very easily result in prescribing change leading to substantive savings for patients, employers, and society.”

Dr. Kim Allan Williams Sr., president of the American College of Cardiology, said he believes relationships between companies and doctors are circular. The more physicians learn about a new drug’s “differentiating characteristics,” he said, the more likely they are to prescribe it. And the more they prescribe it, the more likely they are to be selected as speakers and consultants for the company.

“That dovetails with improving your practice, and, yes, you are getting paid to do it,” he said.

Williams said new drugs are, at least in part, responsible for a significant decrease in cardiovascular mortality in the past three decades.

“If you’re not making strides in this highly competitive area, if you don’t have a product that’s better, it’s not going to fly,” he said. “So the fact that there’s this high relationship in cardiology [between doctors and companies] may in fact be driving the progress that we’re making.”

This story originally appeared on ProPublica as “Now There’s Proof: Docs Who Get Company Cash Tend to Prescribe More Brand-Name Meds” and is re-published here under a Creative Commons license.