In 2012, Medicare’s massive prescription drug program didn’t spend a penny on popular tranquilizers such as Valium, Xanax, and Ativan.

The following year, it doled out more than $377 million for the drugs.

While it might appear that an epidemic of anxiety swept the nation’s Medicare enrollees, the spike actually reflects a failed policy initiative by Congress.

More than a decade ago, when lawmakers created Medicare’s drug program, called Part D, they decided not to pay for anti-anxiety medications. Some of these drugs, known as benzodiazepines, had been linked to abuse and an increased risk of falls and fractures among the elderly, who make up most of the Medicare population.

But doctors didn’t stop prescribing the drugs to Medicare enrollees. Patients just found other ways to pay for them. When Congress later reversed the payment policy under pressure from patient groups and medical societies, it swiftly became clear that a huge swath of Medicare’s patients were already using the drugs despite the lack of coverage.

In 2013, the year Medicare started covering benzodiazepines, it paid for nearly 40 million prescriptions, a ProPublica analysis of recently released federal data shows. Generic versions of the drugs—alprazolam (which goes by the trade name of Xanax), lorazepam (Ativan), and clonazepam (Klonopin)—were among the top 32 most-prescribed medications in Medicare Part D that year.

And it appears these were not new prescriptions.

IMS Health, a health care analytics company that tracks drug sales nationwide, logged only a tiny increase in all benzodiazepine prescriptions, including those covered by Medicare, from 2012 to 2013. That probably means Medicare paid mostly for refills of existing prescriptions, said Michael Kleinrock, director of research for the IMS Institute.

That millions of seniors are taking Xanax, Ativan, and other tranquilizers represents a very real safety concern, said Dr. Brent Forester, a geriatric psychiatrist at Harvard-affiliated McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts.

The drugs are popular because they are fast-acting—working quickly, for example, to quell debilitating panic attacks. But they can be habit-forming and disorienting and their effects last longer in older patients. For that reason, the American Geriatrics Society discourages their use in seniors for agitation, insomnia, or delirium. The group says they may be appropriate to treat seizure disorders, severe anxiety, withdrawal, and in end-of-life care.

Forester said he and others who specialize in geriatric psychiatry don’t use benzodiazepines as a “first-, second-, or third-line treatment because we see more of the downside than the good side.”

Some geriatric psychiatrists worry that doctors may have turned to the drugs in place of antipsychotic medications to sedate patients with conditions such as dementia. In the past several years, Medicare has pushed to reduce the use of antipsychotics, particularly in nursing homes, because of strong warnings about their risks.

In 2013, Medicare covered more prescriptions for benzodiazepines than for antipsychotics.

“At the end of the day,” Forester said, “in terms of risk, the risk with benzodiazepines seems so much worse to me…. There’s significant danger and there’s no spotlight.”

A spokeswoman at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services declined to answer questions about Medicare’s suddenly soaring tab for benzodiazepines.

Some doctors who ranked among Medicare’s top prescribers of the drugs said any risks were outweighed by their benefits.

Fall River, Massachusetts, psychiatrist Claude Curran wrote more than 11,700 prescriptions for benzodiazepines (including refills) in 2013, ranking him behind only four other doctors, all from Puerto Rico. He said the drugs worked well for his patients, many of whom are trying to kick addictions to narcotics but struggle with anxiety and depression.

“First of all, they’re reliable,” he said. “Second of all, they’re cheap because they’re all generic…. They tickle the brain in the same way alcohol does.”

Without benzodiazepines, he added, patients in recovery often need higher doses of methadone, which carries significant risks of its own. “Anyone who’s ever had a panic attack is sympathetic to the use of the benzos,” Curran said. “Anyone who has never had a panic attack doesn’t understand it.”

The vast majority of Curran’s Medicare patients were younger than 65 and qualified for coverage based on a disability. Disabled patients made up about a quarter of Part D’s 35 million enrollees in 2013, but used benzodiazepines disproportionately, accounting for about half of all prescriptions.

Miami psychiatrist Rigoberto Rodriguez also ranked high among Medicare prescribers of benzodiazepines, writing 9,900 prescriptions in 2013, but most of his patients were seniors. Many, he said, are Cuban immigrants who experienced traumas that left them with lingering anxiety, and they have been taking the drugs for years.

Rodriguez readily acknowledged the risks of the drugs for elderly users—recently, researchers found that the longer a person took benzodiazepines, the higher his or her risk of being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. The drugs’ labels say they are generally for short-term use but many patients take them for years.

Rodriguez said he has been working to reduce his benzodiazepine prescriptions in light of emerging research. He expects that when Medicare releases data for 2014 and 2015, his totals will be lower.

“This is fresh information coming out in the last couple years … telling us that benzos are probably not good and you should try to avoid them,” Rodriguez said. “I totally agree with that.”

Roberto Hernando, another Miami psychiatrist who wrote high numbers of benzodiazepine prescriptions in 2013, said he intends to review his prescribing after a reporter told him his totals.

“Some people may need it; some people may not,” he said. “You’re bringing to my attention something that I wasn’t even aware of.”

When Congress created Medicare’s drug program in 2003, there wasn’t much discussion about whether it should cover benzodiazepines.

They were on a larger list of drugs excluded for coverage, along with barbiturates, fertility drugs, and drugs for weight loss and cosmetic purposes. The list mirrored one from a law years earlier allowing states to voluntarily exclude certain drugs from Medicaid programs for the poor. (Medicare now also pays for barbiturates.)

Andrew Sperling, director of federal legislative advocacy for National Alliance on Mental Illness, said it’s unclear why Congress made the exclusions mandatory for Medicare when they had only been voluntary for Medicaid. He believes it was a drafting error.

IMS Health data suggests that while the Medicare ban was in effect, seniors and disabled patients paid for benzodiazepines in other ways. Many paid out of pocket for the relatively inexpensive drugs, which can cost less than $10 for a 30-day supply. Some, particularly those with disabilities, qualified for state Medicaid programs, which continued to cover the drugs even though they didn’t have to. Another set of patients chose Medicare Advantage plans that offered the drugs as an added benefit.

Dr. Michael Ong, an associate professor at the University of California-Los Angeles, co-authored a 2012 paper concluding that many patients continued using benzodiazepines after Congress banned coverage in Medicare Part D and that some turned to more powerful psychiatric drugs.

“Just mandating something and saying we’re not going to pay for the benzodiazepines is probably not the right type of policy solution to change the behaviors of both the providers who are providing these medications and also the patients who are using them,” Ong said.

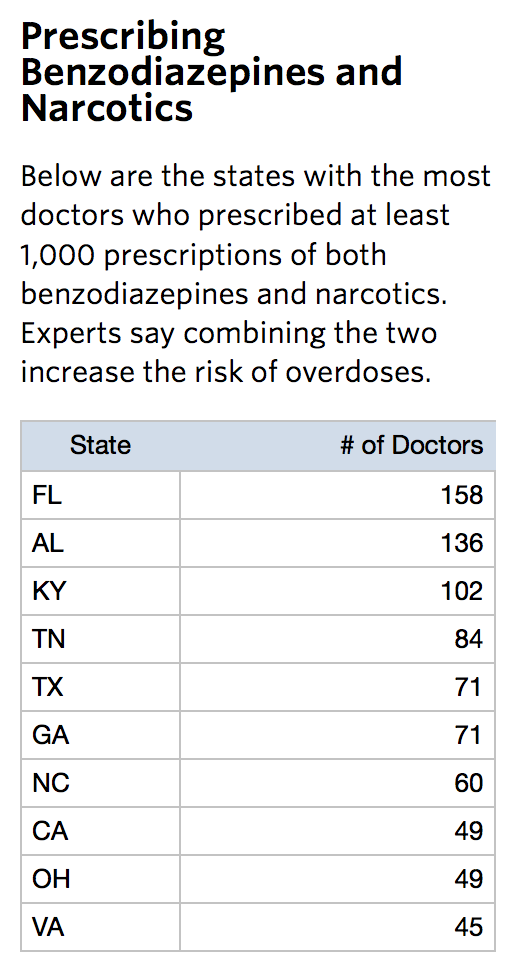

A worrisome aspect of the newly released data is that some doctors appear to be prescribing benzodiazepines and narcotic painkillers to the same patients, increasing the risk of misuse and overdose. The drugs, paired together, can depress breathing.

ProPublica found that this pattern was most common in southeastern states, which struggle with opioid abuse and overdoses. In 2013, 158 doctors in Florida wrote at least 1,000 prescriptions each for opioids and for benzodiazepines, tops in the nation. Alabama, Kentucky, and Tennessee also had unusually high numbers of doctors who often prescribed both narcotics and benzodiazepines. The data does not indicate if the prescriptions were given to the same patients, although that prospect worries experts.

Dr. Leonard J. Paulozzi, a medical epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, co-authored an analysis showing that benzodiazepines were involved in about 30 percent of the fatal narcotic overdoses that occurred nationwide in 2010.

“It increases the possibility of overdoses,” he said.

This post originally appeared on ProPublica as “One Nation, Under Sedation: Medicare Paid for Nearly 40 Million Tranquilizer Prescriptions in 2013” and is re-published here under a Creative Commons license.