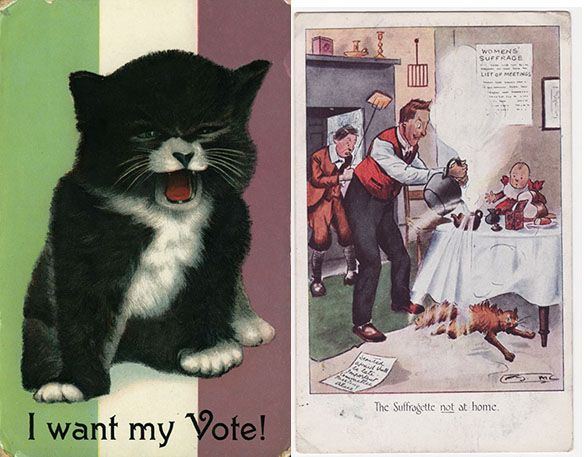

Cats and dogs are gendered in contemporary American culture, such that dogs are thought to be the proper pet for men and cats for women (especially lesbians). This, it turns out, is an old stereotype. In fact, cats were a common symbol in suffragette imagery. Cats represented the domestic sphere, and anti-suffrage postcards often used them to reference female activists. The intent was to portray suffragettes as silly, infantile, incompetent, and ill-suited to political engagement.

Cats were also used in anti-suffrage cartoons and postcards that featured the bumbling, emasculated father cruelly left behind to cover his wife’s shirked duties as she so ungracefully abandons the home for the political sphere. Oftentimes, unhappy cats were portrayed in these scenes as symbols of a threatened traditional home in need of a woman’s care and attention.

While opposition to the female vote was strong, public sentiment warmed to the suffragettes as police brutality began to push women into a more favorable, if victimized, light.

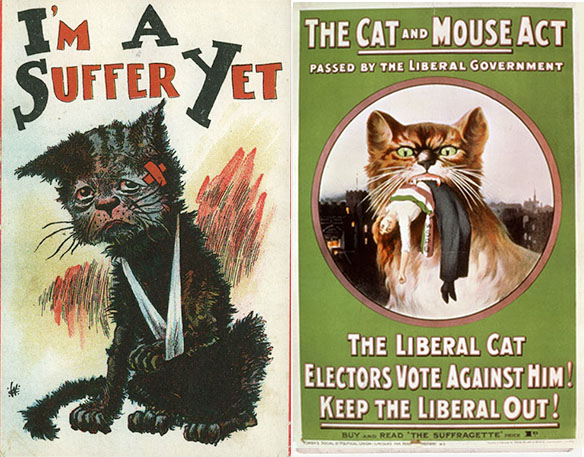

As suffragettes increasingly found themselves jailed, many resisted unfair or inhumane imprisonment with hunger strikes. In response, jailers would often force-feed female prisoners with steel devices to pry open their mouths and long hoses inserted into their noses and down their throats. This caused severe damage to the women’s faces, mouths, lungs, and stomachs, sometimes causing illness and death.

Not wanting to create a group of martyrs for the suffragist cause, the British government responded by enacting the Prisoner’s Act of 1913 which temporarily freed prisoners to recuperate (or die) at home and then rearrested them when they were well. The intention was to free the government from responsibility of injury and death from force feeding prisoners.

This act became popularly known as the “Cat and Mouse Act,” as the government was seen as toying with their female prey as a cat would a mouse. Suddenly, the cat takes on a decidedly more masculine, “tom cat” persona. The cat now represented the violent realities of women’s struggle for political rights in the male public sphere.

The longevity of the stereotype of cats as feminine and domestic, along with the interesting way that the social constructions flipped, is a great example of how cultural associations are used to create meaning and facilitate or resist social change.

This post originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site.