It’s time for another new Superman show. The Christopher Nolan-produced Man of Steel tells the familiar story of our favorite superhero, only this time with a lot of Krypton backstory and a few more elements from a “one man saving the world” epic than we’re used to—just for good measure.

It’s an overtly Christ-themed (if perhaps kinda Mormon) story that critics have said portrays as more complicated and depressing the Man of Steel than we remember from earlier iterations. As Chris Nashawaty at Entertainment Weeklyput it:

He’s been transformed into the latest in a long line of soul-searching super-brooders, trapped between his devastated birth planet of Krypton and his adopted new home on Earth. He’s just another haunted outsider grappling with issues.”

Or he is this time around anyway. The Superman story is one of America’s most retold. Unlike many historical narratives (see The Great Gatsby), this one doesn’t even need to wait an entire generation for a remake.

This is the eighth Superman performance (and fifth movie) in my lifetime. Why do we need to re-imagine this story so often? Well, historically, we have used superheroes to tell tales about a nation, the struggles it’s facing and what decisions it has to make. And because Superman is among America’s most famous and beloved characters, filmmakers need to keep him current. And they usually keep him very current. As Richard Brody wrote in the New Yorker:

Imagine a person who is both endowed with virtually infinite and irresistible powers and is invulnerable to any earthly resistance. What would stop such a person from using those powers to gratify his or her immediate desires? A human tyrant, after all, needs followers and an army; Superman can cow the world single-handedly.

Oh my. How can I remain good despite my vast power? Allegory? It seems every predicament requires a new Superman.

Superman began as a comic book character in 1938, but he wasn’t an all-American nice guy back then. Originally, Superman was aggressive and sort of coarse. He treated people violently. Though he later developed a “no killing” principle, back in 1938 he routinely did the sort of things to villains—abusive husbands, gangsters, and profiteers, mostly—that would cause them to die, even if readers never saw the death portrayed explicitly in the comic books.

He was also a big liberal. The Depression-era Superman often targeted crooked businessmen and razed dangerous tenements. According to comics scholar Roger Sabin, reader in popular culture at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design, Superman’s early behavior specifically reflects “the liberal idealism of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.”

Later on, in the late 1940s, he developed the kindhearted persona and law and order focus familiar to fans today. The personality is also familiar to detractors, who find him plastic and unconvincing and disparagingly refer to him as the “big blue boy scout.”

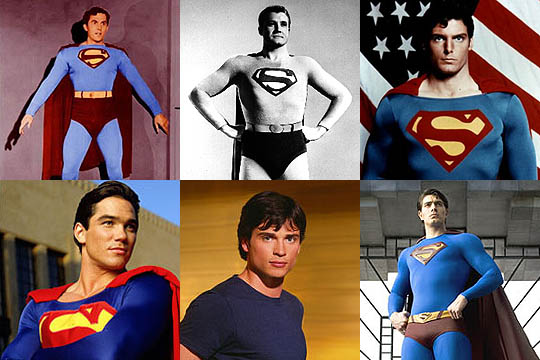

Columbia Pictures made the first Superman movie, a 15-part black-and-white serial, in 1948. It starred an uncredited Kirk Alyn (that’s him in the top image) as the Man of Steel. Superman here was pretty simple. A man is born on a faraway collapsing planet and lands on a Kansas farm. He grows up and gets a job in the city as a newspaper reporter. He helps the world using his superpowers. The problems he faces are modest. He must defeat the Spider Lady. He must avoid Kryptonite. He must take down Lex Luthor. He faces no profound internal struggles.

The 1978 Superman, portrayed by Christopher Reeve, has to divert a nuclear missile that Lex Luthor sends hurtling toward the San Andres Fault so that he can make a fortune in real estate when the dessert he owns becomes the new West Coast—or something like that. This Superman gets upset enough to disregard his father’s instruction not to “interfere with human history” and uses his powers to travel back in time in order to save Lois Lane from death. “I’m here to fight for truth, and justice, and the American way,” Superman says to Lane at one point. He ends up fighting to keep the continental United States intact, a far greater challenge. The threat of nuclear weapons was, of course, a crucial policy issue—and everyman concern—throughout the duration of the Cold War.

In Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman, the ABC television show that aired from 1993 to 1997, the superhero often had to deal with corporate malfeasance and environmental concerns. And in Smallville, the television series that ran from 2001 to 2011, the major struggle facing the young Clark Kent (it’s about him developing into Superman—he’s just a kid), at least in the first few seasons, seemed to be finding his “place” in the world and what to do when he got there.

The problem here is the confusion and potential emotional pain that comes with being Superman. This made a lot of sense in the early 2000s when the U.S., having triumphed over communism, was struggling to defeat terrorism and figure out the next steps in both its economic development at home and foreign policy abroad.

Why does Superman change like this? One of the more interesting struggles societies face as they age is how to keep their stories relevant. Armando Maggi, professor of Italian Literature at the University of Chicago, explains that all cultures struggle with their fairy tales. According to a piece published in the University of Chicago alumni magazine last year:

“These stories were constructed,” Maggi said, as his voice swelled with urgency. “They were invented. And they are very recent stories.” But we cling to them … because we have nothing else to take their place. And so,” he said, “We need a new mythology.”

Superheroes give us the opportunity to create that new mythology. Superman may be an orphan from a distant planet, bestowed with great powers, who lands on a farm in Kansas, and works in journalism (also the blue suit, red cap, S-on-the-chest thing). But that’s just the architecture, the costume.

As Jack Zipes, professor emeritus of German and comparative literature at the University of Minnesota, writes in The Irresistible Fairy Tale: The Cultural and Social History of a Genre, we change our stories from time to time:

As a tale names characters, and makes distinctions among motifs, setting, and behavior, and as certain new stylistic and social applications are introduced or older ones are abandoned, the tale breathes differently—namely, it breathes new, meaningful life into the community of listeners, who often become carriers or tellers themselves. It defines itself differently while adhering to a tradition of tales that may be indecipherable, but is inherent in the telling as well as the writing of a story.

We edit the Superman story for the same reason we edit our fairy tales. We create the heroes we need.

Critics complain that the latest version of Superman, Man of Steel, is “dark” and “brooding.” This is because, unlike the other movies, it concentrates more specifically on Superman’s internal struggles. In early movies Superman never worried about the burden of his skills; there was no sense that he had power that could be corrupted. But in the years since then America has seen seven more movies, one Broadway musical, and four television shows about the hero. Over time, being Superman has become much more difficult. Or as the one relevant contemporary song (which is, I’m afraid, the pop-maudlin 3 Doors Down tune “Kryptonite”) put it:

And if I go crazy then will you still call me Superman?

If I’m alive and well, will you be there holding my hand?

I’ll keep you by my side with my superhuman might

Kryptonite

This is a rather odd worry. Will you still love me once I’ve proven how awesome I am? But this is very much the question of a morally confused world power.

Now, with the U.S. the world’s undisputed hegemon, and with revelations of extensive government spying on U.S. citizens, and continuous problems with drone wars and prisoners held at Guantanamo Bay, the question of how a superpower can use his … er, its … strength is important to us. What can stop him “from using those powers to gratify immediate desires”? It looks like now maybe Superman works (just check the latest box office numbers) because we need our superheroes to address the evil that power could potentially bring—and find a way to avoid it at all costs.