In a Western world of plentiful crop cultivation, packeted convenience, and overconsumption, carbohydrates can be a curse. The sugar in today’s doses is often toxic, and plentiful servings of carb-rich wheat, rice, and corn can conspire with it to fuel plagues of obesity and diabetes.

But in worlds inhabited by our distant ancestors, before agriculture and production lines and Cap’n Crunch, carbs delivered charitable bursts of energy that weren’t so easy to find. It’s not difficult to imagine how evolution ensured that mammals came to perceive sugar as delicious. But now science is unlocking secrets about this hardwired allure of carbs that goes beyond their obviously alluring flavor.

Our mouths possess a subtle sense—one that’s unlike taste or smell. It’s linked to signaling pathways that recognize the presence of sugars, even sans flavor, and trigger a cerebral response.

Our mouths possess a subtle sense—one that’s unlike taste or smell. It’s linked to signaling pathways that recognize the presence of sugars, even sans flavor, and trigger a cerebral response. The response doesn’t just reward our carb consumption with gratifying deliciousness and dopamine. It green-lights the burning of additional energy and improves our physical performance.

Research published four years ago, for example, showed that even rodents with no sense of sweetness showed a glutton-like preference for sugary foods over similarly-caloric proteins. The brains of these taste-stunted rats still released dopamine when sugar was consumed, just as a normal rat’s brain would after chowing down on a cupcake. A body of research dating back to 2008 has shown that merely gargling carbohydrate solution during exercise can boost performance.

To test whether this mysterious carb-detecting sense activated parts of the brain that are independent of those that detect sweetness, New Zealand researchers put healthy volunteers into MRIs. The volunteers were instructed to pinch a device with a particular force whenever a cross was lit up in front of their eyes. During some of the tests, the volunteers swished solutions containing maltodextrin, a relatively flavorless type of sugar, in their mouths. In others, a flavor-matching but sugar-free placebo was used.

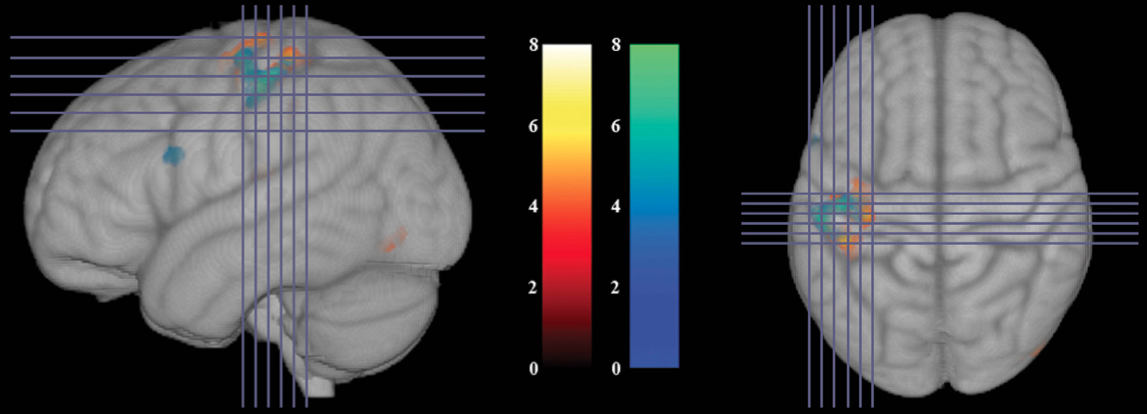

Sure enough, different parts of the brain were activated depending on the solution that was swished. Parts of the left sensorimotor cortex known to be associated with right hand control were activated to a greater extent when the sugar was used. Check out the results of the MRIs, published in the journal Appetite. The red and yellow show areas activated by the carbs; the blue and green were activated by the placebo (numbers in the key refer to standardized scores obtained from data analysis):

MRI results of carbohydrate exposure. (Photo: Appetite)

“Our increased activation in sensorimotor and visual sensory areas show the senses are immediately tuned or heightened by carbohydrate,” says Nicholas Grant, the director of the Exercise Neurometabolism Laboratory at the University of Auckland. “This in combination with immediately increased physical abilities might be the brain saying, ‘Keep doing whatever you’re doing because it’s giving you sugar.'”