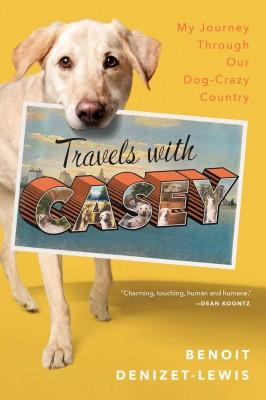

This article is adapted from Benoit Denizet-Lewis’s new book, Travels With Casey: My Journey Through Our Dog-Crazy Country, out this week from Simon & Schuster. To learn more about the book, visit www.travelswithcasey.com.

As I drove around the country with my dog to research a book about dogs in contemporary American life, I met a lot of people who loved dogs. I also met a few people who didn’t.

One such encounter happened at an RV park in New Mexico. As I walked Casey through the campground one morning, we came upon a young woman in a purple robe cradling a bulging toiletry bag and listening to music on her headphones. I assumed she was on her way to the campground’s shower facility. I didn’t have Casey on his leash, and for whatever reason he found the woman worthy of further inspection. He galloped toward her, his head held high. The woman didn’t see or hear Casey approaching, and he made it all the way to her side before she let out a horrified shriek. Her toiletry bag hit the dirt with a thud.

“Get that dog away from me!” she screamed, pivoting stiffly to locate me, the irresponsible dog owner.

I called Casey back and apologized profusely. “I’m so sorry,” I said, as she fumbled to remove her headphones. “He’s friendly and just wanted to say hello.”

“I’d question everywhere I was invited. If there were a chance I’d meet a dog, I wouldn’t leave the house.”

“You need to learn to control your dog,” she said, wagging her finger at me. “Dogs bite.”

“Casey doesn’t bite,” I assured her. “He might lick you to death. But he doesn’t bite.”

She shook her head dismissively. “All dogs bite.”

I wondered if she really believed that. After all, Casey hadn’t bitten her—even as she’d screamed and nearly dropped her toiletry bag on his head. He’d simply backed away, his head down and his tail between his legs. As the woman picked up her bag and walked off in a huff, I was sorry that we’d met this way. I would have liked to have a chance to speak with her about her cynophobia—her fear of dogs.

Those who study animal phobias have found that while more people are afraid of spiders or snakes than dogs, living with cynophobia is considerably more challenging—especially today, as dog-wielding humans appropriate more and more public places.

When I’d spoken to friends (and friends of friends) about living with a fear of dogs, they described a debilitating phobia that affects where they go and who they see. “For the longest time, I would never go to the park because I might come in contact with a dog there,” Margo, a school nurse, told me. “I’d question everywhere I was invited. If there were a chance I’d meet a dog, I wouldn’t leave the house.”

Margo decided to face her fear only when she noticed her daughter mirroring it. “I didn’t want her to have to live like that,” she said. Margo and her husband decided to get a puppy (they named it Casey), and though Margo initially kept her distance, she warmed up to the dog after a week or two. Today, she’s much less fearful when she sees a dog in public. “But I’ll still never be a dog person,” she told me.

Like many women who suffer from cynophobia (men are considerably less likely to be afraid of dogs), Margo can point to an early traumatic incident. When she was five, she fell and skinned her knees as a big dog chased her down a sidewalk. I heard similar chasing stories from others. Robyn, a law student, said a neighbor’s German Shepherd followed her for several blocks while she jogged as a young teenager.

“But little dogs scare me now, too,” she said. “They can creep up on you and then start barking their heads off. You have no idea if they’re going to bite you or hump your leg!”

Robyn worries that her cynophobia will hamper her future. What if she ends up marrying a dog person? What if she can’t go to a best friend’s baby shower because a dog is there? A fear of dogs can seriously impact a person’s social life—and good luck getting sympathy from friends or family.

“Most people just tell me to get over it, as if it’s that easy,” said Sashana, a recent college grad. She hates when coworkers bring their dogs to work. “No one bothers to ask if anyone’s bothered by it.”

Sashana is black, and I asked her if she believed the commonly held stereotype that African Americans are more afraid of dogs than white people. “I wish that were true,” she replied, “because then I could go over to more of my friends’ houses.”

But sociologist Elijah Anderson did find some evidence of racial differences, at least among working-class whites and blacks. In his book Streetwise, about a diverse urban neighborhood in Philadelphia, he noticed that “many working-class blacks are easily intimidated by strange dogs, either on or off the leash.” He found that “as a general rule, when blacks encounter whites with dogs in tow, they tense up and give them a wide berth, watching them closely.”

Kevin Chapman, a clinical psychologist at the University of Louisville, noticed the same anxious behavior among many African Americans that Anderson found. Chapman also discovered that nobody had explicitly investigated the incidence of cynophobia in African American populations. So in 2008, he and several colleagues conducted the first of two studies looking at the prevalence of specific fears across racial groups.

Compared to non-Hispanic whites, they found that “African Americans in particular may endorse more fears and have higher rates of specific phobias”—particularly, of strange dogs. When we spoke, Chapman offered two possible reasons. First, many dogs in low-income urban areas are trained to be what he calls “you-better-stay-away-from-our-property” guards. Being wary of those dogs makes sense—many of them are scary. In addition, Chapman told me, there’s “the historical notion of what dogs have represented for black folks in America.” In the antebellum South, dogs were frequently used to capture escaped slaves (often by brutally mauling them), and during the civil rights era police dogs often attacked African Americans during marches or gatherings.

As Chapman and his colleagues wrote in their 2011 study, many African Americans were psychologically conditioned to fear dogs when the animals were used as tools of racial hostility toward the black community. That conditioned fear is transmittable through families, he explained, and has contributed hugely to a community-wide fear of canines.

But though it seems that African American history has fostered a fear of dogs among some blacks, cynophobia mostly affects people who are conditioned to fear dogs and are predisposed to anxiety. When coupled, Chapman explained, environmental conditioning and genetic predisposition are “powerful enough to make someone develop a significant or substantial clinical fear of anything.” And people who are that afraid—who have what Chapman calls “a legit phobia of dogs”—don’t discriminate between canines, regardless of how their fear is conditioned.

“It may begin with a Rottweiler or a Pit Bull, or something that is stereotypically trained to be vicious,” Chapman told me. “But if you’re conditioned to think they’re dangerous, that fear gets generalized to, say, Shih Tzus and Chihuahuas.”

Regardless of race, those seeking help for their canine phobia have several therapeutic options. The most effective is in vivo treatment, where a therapist walks a person through instructions of increasing difficulty with a heavily trained dog, from leading the animal on a leash to, in the case of a brave patient, putting a hand in the dog’s mouth. But as Margo proved when she and her husband came home with a puppy, you don’t always need a therapist to recover from cynophobia. Sometimes, you just need to hang around a friendly dog.

When I’d visited Dr. Joel Gavriele-Gold, a Manhattan therapist who includes his dog in therapy sessions, he told me that one of his previous dogs, Amos, was helpful for patients who were afraid of dogs. One woman had been so frightened by the prospect of Amos lunging at her in his office that Dr. Gold promised a year of free therapy if the dog so much as approached her. She left treatment sometime later “kissing Amos on the head.”