In the 1920s a German workers’ sports organization, ARB Solidaritat, become one of the largest cycling organizations in the world. It had more than 300,000 members, and its own bicycle factory, workshops, inns, and an insurance system. The organization celebrated the affordability of cycling and the freedom it allowed workers, but in 1933 ARB Solidaritat was banned by the Nazis. It was re-established in 1945, but never quite re-gained its earlier popularity. Twenty years later, ARB Solidaritat dropped the term Arbeiter (workers) from the name and today few visible connections exist between the organization and the historical workers’ movement.

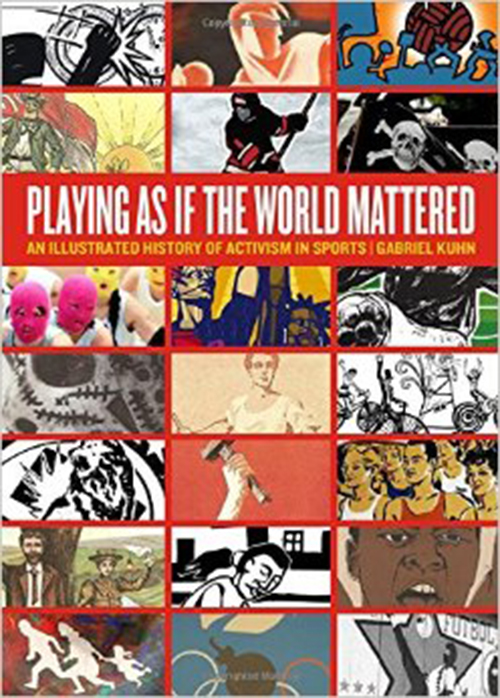

The history of ARB Solidaritat is just one thread of many documented in Gabriel Kuhn’s Playing as If the World Mattered: An Illustrated History of Activism in Sports, released earlier this year. From the workers’ sports movement of the early 20th century to the civil rights movement in the 1960s to today’s grassroots operations, Playing as If the World Mattered traces more than 120 years of activism in sports, and highlights the liberation and social change sports can provide.

In 2011, Kuhn, a former semi-pro soccer player, wrote Soccer vs. the State: Tackling Football and Radical Politics, which documents the sport’s history, reflects on common criticisms, and explores the contemporary landscape of the sport. Much like that earlier title, Playing as If the World Mattered peels back the commercialism and exploitation of sport to reveal how the games we play not only explain the world, but, at their best, can improve it for the better.

Pacific Standard reached him at home in Sweden.

Why did you want to collect and share this history?

Some of it is simply not very well known. The workers’ sport movement, for example, was a mass movement, but it has disappeared from most history books, including socialist ones. The main reason, however, was that I think sports are underrated as a subject within the left. It is either rejected as a pacifier for the masses or, in the best case, tolerated as an acceptable emotional relief for battle-scarred activists. But I think that sports is at the heart of the struggles we need to engage in: it is a mass phenomenon; it transcends boundaries of class, race, gender, and other social dividers; it bundles emotions and aspirations; and it teaches us plenty about community, respect, and fairness.

How did you decide on the individuals and organizations that are included, and the illustrations that accompany them?

It is unavoidable that my own background—in terms of where I grew up and the sports I grew up with—is reflected in the selection. But I have tried to follow objective criteria regarding the significance of events and projects for social and left-wing movements.

The images were selected according to different aspects: they needed to be representative and expressive with respect to the issue at hand; they needed to be aesthetically appealing; they needed to be available in the form of high-resolution scans; and they needed the permission of the respective artists, photographers, and archivists to be used. In some cases, I found images that satisfied all of these needs, while, in others, I had to compromise.

It was a lot of work, but, in the end, I was very happy with the selection. The only regret I have is not finding a good image of Billie Jean King who would have certainly deserved her own entry. Billie Jean King had a tremendous impact on the emancipation of women tennis players and women athletes in general.

Are there any sports movements that you’re particularly close to?

I’m a history nerd and therefore really captivated by the workers’ sport movement. It was a tremendously ambitious attempt to administer sports based on uncompromised socialist values. We can only dream of such a movement today. However, there are great contemporary initiatives too. Among the most interesting for me are supporters taking over professional sports clubs as cooperatives; the organizing efforts by anti-fascist and anti-racist sports fans; and the network of grassroots clubs that attempt to establish a world of sports away from the hyper-commercialized spectacle presented to us by corrupt power-mongers.

How important is it today, in this era of both hyper-commodified sport and social unrest, to remember what sport is capable of achieving?

It is terribly important. Sport reaches the masses like few other social activities do. There is a reason why those in power have been preaching the separation of sports and politics for such a long time. If athletes, supporters, and managers revolutionized the distribution of power in sports, the impact on society would be immediate and far-reaching; due to its popularity and inspirational force, sports would become a major instigator for social change. Yet even as individuals, politically conscious and outspoken athletes can have a tremendous influence. We know of a few exemplary folks such as Muhammad Ali, Roberto Clemente, or Billie Jean King. But think what would happen if all athletes were like them.

Are there any current athletes or organizations that could earn a place in a future edition of this collection?

There have been a few interesting developments since I finished the book. In the United States, several professional athletes have come out in support of Black Lives Matter and related campaigns against police violence and racial injustice. In Europe, there has been huge support among both individual athletes and clubs for refugees arriving from impoverished and war-torn countries. In light of the most recent FIFA scandal, interest in independent soccer leagues and tournaments has grown stronger than ever. And even in alpine skiing, usually bereft of any critical voice, prominent figures such as Marcel Hirscher and Felix Neureuther have raised concerns regarding the commercial interests dictating the decisions of the International Olympic Committee. These are all very encouraging signs.

In your own background, as a semi-professional soccer player, did you see firsthand the way sports can effect change?

In the 1980s, when I was a teenager playing for a second-league team in Austria, one of my teammates was a co-founder of the country’s first union for soccer players. Unfortunately, I was too young at the time to fully appreciate the significance of this. Players’ unions are often misunderstood as organizations helping millionaire athletes to make even more money. The reality is that millionaires among athletes are a small minority. The vast majority of today’s professional athletes belong to what has become known as the precariat: an unstable workforce with short-term employment, weak labor rights, poor protection against contract violations as well as injuries, and few alternative career choices.

What was obvious to me even as a young player was the potential of sports to transcend social boundaries. While class was a highly stratifying factor in the high school I went to, the relevant hierarchies were leveled, or even turned upside down, on the playing field. The same could be said about the ethnic divisions that characterized daily life where I grew up. There is no point in romanticizing, but sport’s integrative potential is one of the reasons it is so popular across all sectors of society. If this potential could be expanded to society at large, significant changes would inevitably follow.

The Sports Lens is a running series exploring the intersection of sports and culture.