There is much more to be found in Chicago than violent crime, though press on the city often focuses on it. Like any city and the people who live in it, Chicago is home to more nuance than news will cover—including stories of hope, learning, family, and love.

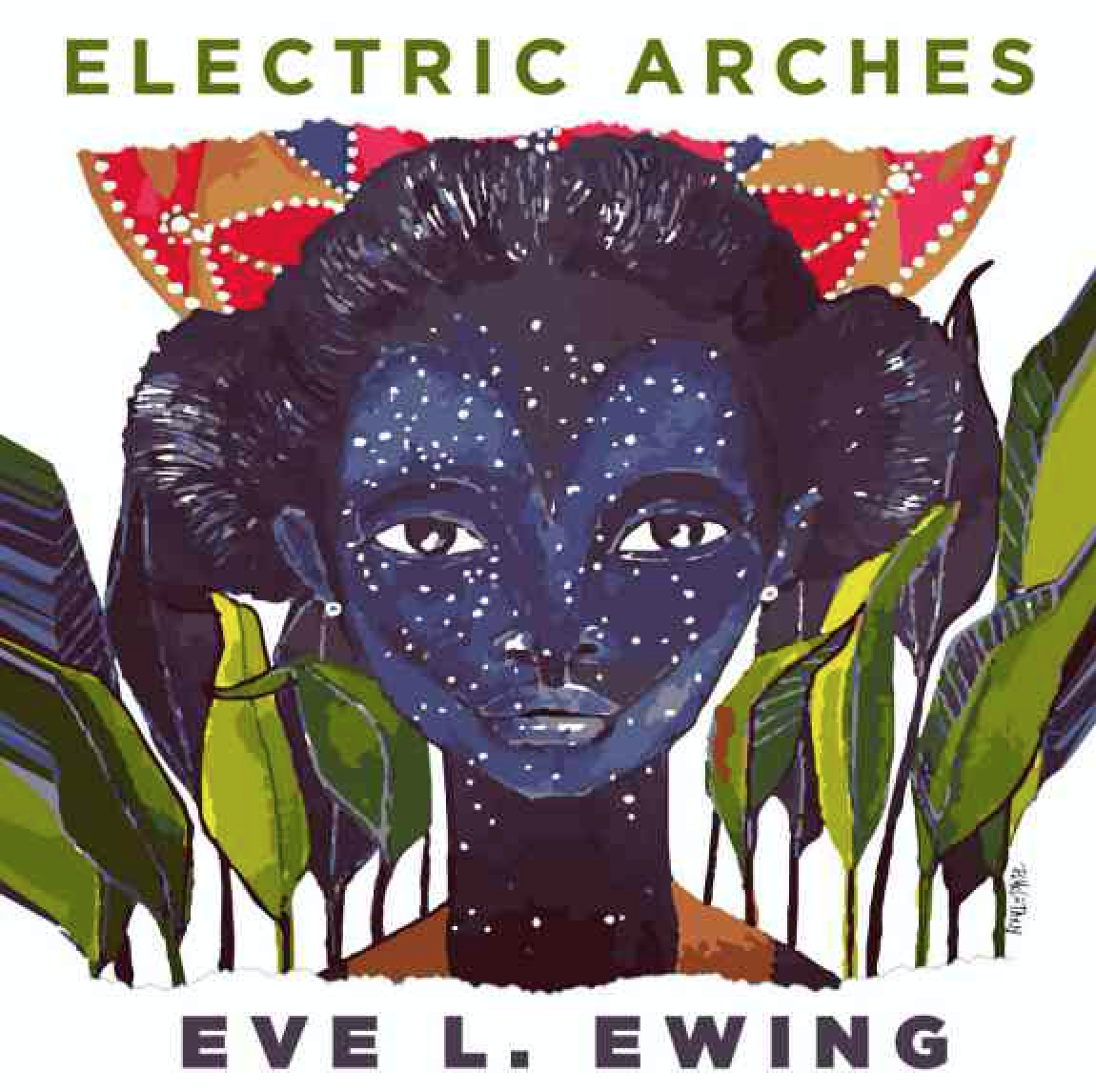

In her debut book of poetry, Electric Arches, released last month from Haymarket Books, poet, essayist, and sociologist Eve L. Ewing offers outsiders such an alternative view. Her short stories and poems are about growing up and living in Chicago; some are Afrofutrist fantasies about a “free black future,” as Ewing has said. Ewing focuses on children, school, celebrities, and activists, positing that discussions of city life and justice can take many forms.

The work in Electric Arches is often deeply personal. From a poem about a young student based on one she knew (titled “the notebook kid”) to a short ode to the now-closed Discount Megamall on the city’s northwest side, Ewing elicits beauty from her everyday experiences. She incorporates broader political statements into the collection as well. Electric Arches’ first poem, “Arrival Day,” begins with a quote from civil rights activist and former Black Liberation Army member Assata Shakur: “Black revolutionaries do not drop from the moon. We are created by our conditions.” Shakur’s words echo throughout Electric Arches’ works, which include various narratives about origin—in “Arrival Day,” black revolutionaries arrive on Earth from the Moon; in “Origin Story” and “At work with my father,” Ewing remembers her youth and her family.

The result is at once a portrait of her home, a tender letter to black youth, and a call to her audience to think beyond the confines of systemic racism. In an interview with Pacific Standard, Ewing discussed the role children played in the creation of Electric Arches, how her sociological and artistic projects intersect, and how Assata Shakur informs her work.

The poems in Electric Arches are so tender, and many of them are about children and childhood, black childhood in particular. Did you have a young audience in mind for this book?

Oh, very much so. What I hope is that it’s a book that young people will find appealing, resonant, and harmonious, and that will speak truth to their own lives. It’s something people can have a relationship to across their lifespan: I hope some people will find something in it when they’re young, and then find something different in it 10 years from now or 20 years from now. But it’s very much written with young people in mind.

Along with being a poet and essayist, you’ve also been an educator. Can you talk a little bit about how your work with students influenced Electric Arches?

I was a language arts teacher and I taught middle school, sixth, seventh, and eighth grades. And I continue to work with a lot of young people through poetry in out-of-school settings. But usually when I work with young people and poetry outside of school, it’s something where they’ve opted in, it’s something they’re interested in. Whereas when I was a public school teacher, the state has mandated that the students had to study literature for this many minutes a day.

[The public school scenario] is a challenge that’s really exciting to me, and as a teacher something I really loved was curating literary experiences based on my students’ interests, and trying to find different things that would be interesting to them. [Or] trying to find context and information and access points for different kinds of literature [so] that it could be exciting and relevant [to them]. That helped me a lot in writing this book because I had very real people in mind as audiences. It definitely wasn’t something where I was thinking of a nebulous, fake teenage person—I thought about particular young people, and the poems are very much for them in a lot of ways.

In an interview about your book, you said that it’s about a “free black future,” which “demands an honest reckoning with a violent and traumatic past.” How does poetry allow you to discuss these subjects in a way that other writing can’t or doesn’t?

I think the thing you’re asking that’s particularly interesting is around questions of violence and trauma, and thinking toward solutions to social problems. Poetry allows for us to lead first with the heart. And I think that, in academic writing, oftentimes there’s a tendency to talk about things that are really deep, traumatic, and complicated in a way that’s very abstract and distanced. But it’s a different access point for people, because people go to poetry because they want to feel something, you know? With poetry, you can bring readers in because they want to feel something and they can walk away thinking about something that they didn’t expect to think about.

In terms of imagination and transforming the world, I love writing about social transformation through poetry because the sky’s the limit. Creative writing allows you to tackle impossible social problems in limitless ways. And I think that’s really exciting, but I also don’t see that as a pie-in-the-sky exercise. I think it actually allows us to do the work of envisioning what lies beyond, and a pathway toward getting there.

After the 2016 presidential election, you said of the obstacles that society faces under Trump, “All fights begin at home.” Many of your poems are set in Chicago, which is your home. What do you see as the fights in Chicago right now?

I definitely think there’s the fight to imagine a world beyond violent, oppressive policing. And that fight very much transcends the city, and is really about the history of our country, the history of urban spaces, and the history of race and racism in the United States. But Chicago is one place where it’s very much under the magnifying glass. That’s something I’ve been thinking about in terms of the question, “From whence does justice come?”

So for example, the Department of Justice can create comprehensive reports that say [something like] “problems within policing are structural and they are endemic to the very fabric of the institution of police.” So a lot of what I try to do as a sociologist is push people to think about structures rather than individuals. And it’s really hard because American society encourages us to lean toward hyper-individualism; it’s pervasive in everything from movies and television to events like the State of the Union address, where the president will say, “Here’s Wonderson who started a small business, stand up and we’ll all clap for you!” Given these narratives, it becomes uncomfortable and intellectually difficult to understand that there are things that transcend us as individuals. So that’s something I think I’m puzzling through in Chicago, and is obviously a national issue. And also: segregation, poverty, the changing face of the American city. I think about all of this all day.

The first poem in the book begins with a quote from the activist Assata Shakur, and the final poem references her as well. How does Shakur and her story factor into your vision for the future?

When I first picked up Assata Shakur’s autobiography, I was blown away to find poetry in it. So the final poem in Electric Arches, “Affirmation,” is for a poem by Shakur of the same title. I love that poem because it allows us a space to use imagination to think through what liberation looks like. There’s a great line in that poem: “And, if i know anything at all / it’s that a wall is just a wall / and nothing more at all. / It can be broken down.” That simple assertion allows us a space to imagine the world without walls. It doesn’t beg of us easy answers in the moment, but it allows us the space to imagine.

Something I’ve been thinking about is how her place in American history is so contested depending on who you ask. I’m interested in that because part of what I’m trying to do in all of my work is reconfigure the way we think about history; to understand history as something constructed, and not something that comes to us from a tablet on the mountain. For example: Thomas Jefferson is a hero and the forefather of this country. That is the foremost truth that we are to understand about Jefferson, instead of the fact that he held human beings in bondage. It doesn’t have to be that way. That typifies the kind of work I’m trying to do more of.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.