Juan Haines is the kind of old-school editor who’s disappearing in American newsrooms. He talks to his reporters face to face. He keeps copious, handwritten notes in an orderly notebook. He’s hard-headed when he needs to be; soft and funny when that’s called for; a dogged reporter and a thoughtful proofreader. He’s intensely familiar with his reporters’ beats and the context in which they are working—and he should be. He’s eaten, slept, lived, and worked there for 23 years.

I met Haines the first time I visited San Quentin State Prison (where, full disclosure, I am a volunteer). He has worked in various editing positions at San Quentin News, one of the country’s only prison newspapers, for almost a decade. There, he helps produce a 20-page paper every month with only a few computers and no Internet access. The results reach 30,000 incarcerated and free subscribers across the United States.

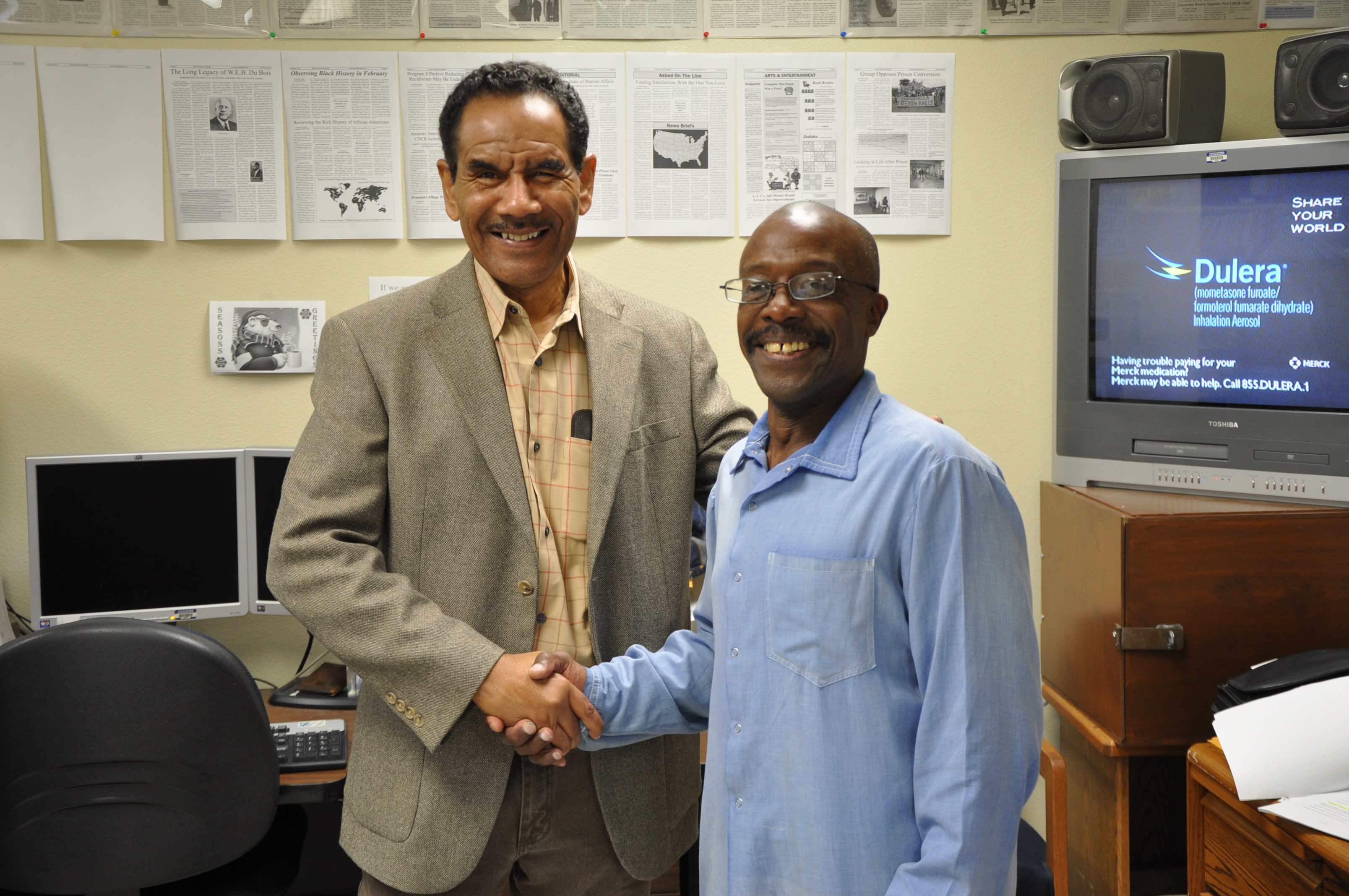

Now Haines is spearheading a new project, Wall City, a magazine of prison culture. We sat down recently at San Quentin’s media center to talk about rehabilitation, press freedom, and what journalism can and can’t do for incarcerated readers.

Since you’re also a journalist, I thought we could start this together. If you were me, trying to set the scene, how would you describe it? And how would you describe yourself?

We’re in the San Quentin News office, nestled away in the back of the lower yard. You go through a heavy steel corrugated fence, then walk into this fairly large office. There’s double-screen computers, a big desk in the middle.

I’m 61, kind of short, skinny, balding, missing tooth in the front. Energetic. I’m a Navy brat. I grew up mostly in San Diego County. I did two stints in the Army; both ended not so well. Then I started getting into trouble, had drug and alcohol problems.

But there’s other things that people always want to know about me. No. 1, I’ve been in prison for the past 23 years. I’m in prison for multiple bank robberies that I committed in 1996 in San Diego County. I was sentenced to 55 years to life.

How do you feel about that when you think about it now?

I don’t want to say that I was stupid, but I was disconnected. I wasn’t in reality. Because that was just totally inexcusable. I neglected my family, neglected the children in my life, absolutely shut myself off. Shortly after I was arrested, I called my wife, and she told me that she thought I wanted to be in prison. I didn’t understand that then. I thought that was a really cruel thing for her to say.

But that phone call stays with me, and I go back to it a lot. When I objectively examine what I was doing and how I was living my life, I could see where she was coming from. I have five brothers and two sisters. I have so many nieces and nephews I can’t count them. However, if you had asked me what their birthdays are or who they are I couldn’t have told you. Because that’s that type of person I was. I wasn’t focused on how I affected other people’s lives.

After 23 years in prison, I have slowed down my thinking. I really care about how I affect other people. I’m mindful of who I am, what I do.

You got involved in San Quentin News not long after you arrived here. How did that happen, and what has journalism meant to you in prison? Has it been part of the ways that you’ve changed?

A really good friend of mine, Arnulfo Timoteo Garcia, was a member of the journalism guild. He would always come get me when he wanted to interview someone. He had these composition books, and he’d fill them up. I always asked: Why did you write that down? I mean, the guy sneezed, and Arnulfo wrote it down.

Eventually, Arnulfo told me, I want you to come to San Quentin News full time to be the managing editor. One of the most important things to me about San Quentin News is the style of news that we report, which typically deals with transformation. When someone’s loved ones read about their relative, it’s different than how they knew that person when they first became incarcerated. You know, “Juan Haines, arrested for bank robbery May 10th, 1996,” and that’s what they read about me in the newspaper. However, when a person’s loved one reads about their incarcerated family member in San Quentin News, it’s a story about a graduation, completing a coding class, participating in a self-help group. That allows the person’s loved ones to see their incarcerated family member in a completely different way.

(Photo: San Quentin State Prison)

Tell me a little about your workday.

Usually about 8 o’clock, I’ll come down to the office. I supervise the staff writers, and so whatever they write, I’ll review that. Then I have several projects that I’ll be working on. I’ll check with the editor-in-chief to see what he wants me to do.

I guess free people have their devices, and they’ll check off what their appointments are. Well, I have a notepad with little square boxes that I draw, and then I write what that particular task is—call this person, schedule this, and I’ll go down that checklist to try to complete it. I usually edit anywhere from 30 to 40 stories a month, and I usually write five or six stories.

Why does a prison need a newspaper? And why does a prison need a magazine?

Prisons need newspapers for the same reasons that the public needs newspapers. Communities need to know what’s happening locally in order for them to make better decisions in their daily lives. It’s really important for people who made mistakes, some horrible mistakes, in their lives to be given information to where they can make better decisions. And so what the magazine does is it allows us to take selected stories and put them in a longer form, so that we can go even more in-depth on how this transformation really works for people.

Tell me about press freedom inside San Quentin. I know everything you publish has to be approved. Do you feel like there are things that you can’t write about?

There is no censorship in anything that we write. We have our First Amendment rights. That being said, there is an approval process. Our stories have to go to the Sacramento press office [of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation]. What the administration looks for are security concerns. Are we sending coded messages to other inmates to do stuff? That’s the only purpose of the administrative review.

Still, we’re cognizant that words have power. We know the news that our audience needs. We want to say things to other incarcerated people that we know help because it’s what would have helped us. We don’t want to report on prison violence, although we could probably sell hundreds of thousands of papers if we only reported on that. But we’re more about wanting a mother to read about her son in a basketball game against an NBA star or getting a high school diploma.

Do you ever find yourself practicing self-censorship, then?

Oh yeah, all the time. I had an inmate tell me about a crime before. I said: “Why are you telling me this? Have you ever been prosecuted for this?” The parole board reads the newspaper. I have to think about what I’m doing to the subjects who I report on and if I’m going to do damage. [Interviewer’s note: I followed up with Juan soon after this conversation and asked again if he really hadn’t ever experienced censorship from the prison administration. He thought for a few moments and then responded that, on a couple of especially sensitive stories, he just didn’t receive a response, which usually meant he was unable to publish them. He says he didn’t really see that as censorship, though.]

Yes, I can see why representation might be a tricky issue here. How does that play into Wall City magazine? I know the first edition came out this year, and the second one is about to go to print.

Wall City was Arnulfo’s idea. He had always felt constrained with the word count in a newspaper. It goes back to the days when we sat down in those interviews, and he’d have that composition book full of all these details. He wanted to talk about people who returned to the community. He wanted to talk about the people who came out of the Security Housing Units, the SHUs. The stories we’re working on right now deal with gun violence, suicide prevention, and gang issues. Arnulfo saw an opportunity with the magazine to bring people’s lives out into the light.

I know it might be painful, but can you talk about how you ended up being the editor of Wall City?

Arnulfo had been in prison for 22 years, and he pretty much changed the lives of everyone he came in contact with. Then the greatest thing happened. Everyone saw the transformation in Arnulfo, including the district attorney that sent him to prison. That district attorney was instrumental in advocating for Arnulfo’s release. Arnulfo went back to court, and the judge agreed. And then two months and two days after he was released, he was killed in a car crash.

It devastated us in the office. There was just so much left for Arnulfo to do. I feel obligated to carry on his legacy.

I can only imagine. That story hurts me every time I hear it. Since Arnulfo wanted to promote understanding, what is one thing that you wish that people outside understood about life in prison?

When people are hurting, there’s a ripple effect. When you leave a person in a state of hurt, then that’s all that person knows. But when you allow that person to better themselves, there’s a ripple effect there also. When I run across a rookie correctional officer, I know that he or she is apprehensive, and so I’m careful. I want that person’s experience on the job to be one where there’s compassion. When I exercise that, I can physically see the difference.

As somebody who’s not inside, my understanding has always been that you gotta be tough, and that showing kindness is weakness.

That’s a fallacy. You’re looking to me, this skinny 61-year-old guy. I barely weigh 120 pounds, but I get out there and play basketball with 20-year-olds. And I run circles around them. Sometimes they get mad.

But then when they see me smile my toothless grin, that softens them. I put an arm on their shoulder, no matter how the big the kid is, and I’m just kind to them. Kindness goes a long ways in this world, and people just don’t understand how powerful just a smile is.

Even in prison?

Even in prison.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.