IT’S A SUNNY SPRING DAY at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory outside Los Angeles when I show up at Kevin Hand’s office to talk about his work with Ridley Scott on the new film, Prometheus, a sort-of prequel to the Alien series. But it seems only polite to ask first about the trip Hand has just returned from: a quick expedition to the middle of the Pacific Ocean with another star director, James Cameron, who was taking a custom-made submarine on a historic dive to the deepest point on Earth.

Cameron spent three hours at the bottom of the Mariana Trench, 33,000 feet below the sea, the longest anyone has ever stayed at that depth. Hand was on the sub’s mother ship, tasked with doing on-board analysis of samples Cameron brought back from the depths. “It was a pretty incredible thing to be part of,” says Hand.

Hand’s job itself sounds like something out of a movie: he’s an astrobiologist who spends his days searching for life on other planets. So it’s perhaps not too surprising that he has a sideline consulting with some of Hollywood’s top science fiction directors. A growing number of filmmakers are turning to researchers like Hand in an effort to give their fantasies a stronger basis in scientific reality. In the last four years, the Los Angeles-based Science & Entertainment Exchange, which promotes collaboration between Hollywood and the world of research, has arranged for hundreds of scientists to give advice to the makers of films and TV shows from Tron: Legacy to House and Lost.

Movies are part of the reason Hand went into science. Growing up in rural Vermont, he was captivated by Close Encounters, E.T., and Carl Sagan’s Cosmos series. “I’ve always been obsessed with life on other worlds, since I was a kid looking up at the stars,” says Hand, a trim, mellow-voiced 36-year-old with a gelled-up wave of hair cresting over his high forehead. “I’m still asking the same question: is there life beyond Earth? But now I do it with a lot more tools.”

Among other things, Hand helps run NASA missions to survey the outer solar system. Some of the frozen moons orbiting planets out there are currently the most promising prospects for extraterrestrial life, especially Jupiter’s Europa. Across the hall from his office, Hand oversees a lab he calls “Europa in a can,” where he and his research partners try to recreate the moon’s atmospheric and chemical conditions inside a concatenation of gleaming canisters. “I love Mars, but there, we’re looking for evidence of past life. The search for extant life points us to Europa,” he says. That’s because scientists are all but certain that there’s a literal ocean of water beneath the moon’s frozen crust. “If we’ve learned anything about life on Earth, it’s that where you find liquid water, you find life,” says Hand.

A key aspect of Hand’s research is figuring out how life can exist amid intense heat, cold, and other extreme conditions. His work has taken him to the north slope of Alaska, the glaciers of Mount Kilimanjaro, and Antarctica. A blown-up photo on the wall of his small but bright office shows the camp he stayed in down there—a speck of a tent in a corner of a vast, ice-corrugated terrain.

Hand first worked with Cameron on Avatar, and then with the producers of the superhero movie Thor. He gave the filmmakers pictures of Europa to help them design a halfway-plausible icebound home planet for Thor’s nemeses, the Frost Giants, and convinced them to make that planet round instead of a physics-defying flat plain.

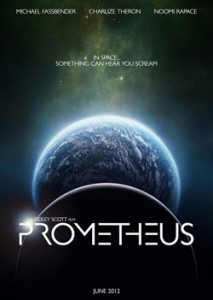

For Prometheus, he met with Scott—the legendary director of Blade Runner, Gladiator, and Alien—and his team at their offices in Beverly Hills. The movie is about a team of space explorers, played by the likes of Charlize Theron and Michael Fassbender, whose pursuit of clues to the origin of life on Earth leads them to a distant planet full of dangerous aliens. Scott and company wanted to know more about what other planets actually look like. “I gave them a tour of the solar system, about the bizarre things we know about moons, and the incredible weirdness of Mother Nature when it comes to worlds beyond Earth,” says Hand. “Creative as these artists can be, they’re often tethered to things we know. That’s why you always see aliens in hominid form. But Mother Nature comes up with things like Titan’s methane lakes and orange atmosphere, or Europa’s ice cliffs.”

Hand also weighed in on the aliens themselves, advising the filmmakers on what biological constraints reality imposes on even extraterrestrial life. “It makes a better film when the makers get the science right,” says Hand. “Look at shows like CSI. They do well in part because they present puzzles that need to be solved through science.”

“At the end of the day, though,” he concedes, “these guys are telling a story. If the science is too meticulous, it gets in the way.” Hand isn’t expecting to find any multilimbed, big-eyed aliens on Europa when NASA sends its next probe out there, some time in the next decade. He’d be delighted to find microbes. That’s not exactly material for the silver screen. But finding star-quality life on another planet? That would be a blockbuster.