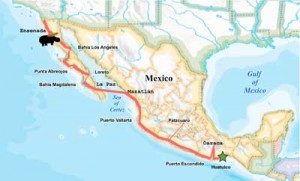

El Hippo continues it’s journey south, finding an overturned fishing boat that comes to symbolize the plight of the world’s suffering fisheries.

Location: On a sandy bluff next to a fisherman’s house in Punta Cabras, a few hours south of Ensenada.

Conditions: Hot and dry. The swell is smaller than yesterday, when the panga capsized.

Discussion: The open fields were golden in the afternoon light, when we arrived in Punta Cabras. Further from the coast, the earth seemed to warp into hills and mountains, like a wrinkled carpet that a little boy pushed together as a landscape for his toys. That first night, under a starry sky and waning new moon, we found a beachside bluff to camp, next to the baritone rumble of the ocean. With help from our two-burner propane stove we ate pollo asado (the ubiquitous roasted chicken that is sold on most street corners), homemade coleslaw and drank a glass of wine. There was much rejoicing: We were in the open country.

The next morning was warm, but I discovered the water was freezing, while surfing small beach breaks in front of our camp. After a mighty breakfast and coffee, we rode our bikes along the ranch lands, kept mostly undeveloped by the rugged terrain and increasing distance from the border. Past a hillcrest, the markings of a fish camp: a deserted trailer, some junk cars and a few pangas — the 14-foot cabin-less boats that are commonly used for fishing in Baja.

When we returned, a sight startled us. A white panga — that we had seen in the morning bobbing offshore — was now upside down and dangerously close to the breakers. Three men clambered on top of the overturned hull as it drifted slowly toward the waves. On the beach, a few men were scurrying about frantically, trying to figure out what to do. One of them was the fishermen’s cousin; after I talked to him for a minute, we decided to paddle out with my surfboards and try to assist. Just as we were about to enter the water, fortunately (for the fishermen, and us too!) a rescue boat arrived, which had been summoned earlier by the cousin, and it whisked the men away to safety.

According to the cousin, the men had been diving for clams when a rogue wave hit them sideways and caused the capsize. I was surprised when I saw the panga on shore later that afternoon, fully intact, after being dragged onto the beach by the men; and I was ashamed that I had missed the whole endeavor, having fallen asleep during a particularly deep siesta, only waking up to the grumbling of their trucks as they left to repair the now un-submerged outboard engine.

They left smiling and relaxed — it was all in a day’s work. Despite the tribulations, the fishermen like the sea and their life by the coast. They sell the clams and urchins to the Japanese market, which brings enough money to pay for their 4×4 pickup trucks and sturdy boats that can handle an occasional capsize.

“It’s better here,” said Jorge, the fisherman who lived at the house next to our campsite. Jorge used to live in Tijuana and work across the border but had relocated to Punta Cabras. His house was simple, built like a large shed of materials that happened to be available. Jorge told me, gesturing with his hands, “The air is clean here, no violence, you know? The ocean is good to us — most days! Flip sometimes and not much money sometimes, but it’s OK. I like the wind.”

I hoped that these men could continue their livelihood by the sea for a long time. Fisheries are already a tough business — and fish stocks can and have collapsed due to overfishing or ecosystem stress. Prime examples include the North Atlantic cod fishery and many salmon fisheries. Now climate change may also accelerate the decline of worldwide fisheries, due to the twin problems of ocean acidification and ocean warming.

These physical processes are well studied, according to a 2009 report by International Union for Conservation of Nature. Since the Industrial Revolution, ocean acidity has increased 30 percent. Excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere descends and mixes with water to produce carbonic acid, which in turn weakens the carbonates that shellfish need to calcify and create their shells. Coral reefs may also fail to calcify — intensifying what is already a global catastrophe. Coral reefs, which are habitat for a huge array of marine organisms, and support the coastal livelihood of millions of people, have been dying in huge numbers due to bleaching associated with warm water. During the 1998 El Niño phenomenon alone, it was reported that 16 percent of the earth’s tropical corals perished.

The eastern Pacific, where Baja California is located, is in a better position than most. The strong westerly winds common to this area drive upwelling from deep ocean trenches and brings up cold water — the storehouses of nutrients. For this reason, the fishermen in Baja may have enough clams, lobster and fish for their lifetime — and people everywhere can continue to enjoy seafood. If the ocean is as bountiful and resilient as we hope, perhaps a few more generations of fish camps and capsized pangas will bless this coast.