The strangest part of the Rachel Dolezal saga—stranger than the former head of the Spokane, Washington, branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People being “outed” as a white woman by her own parents after years of passing as African American, stranger than her passing off her adopted black brothers as her own children, and stranger than Dolezal’s lawsuit against historically black Howard University for discriminating against her for being white—is that she may be a sign of things to come.

While the entire Internet is flipping out over Dolezal’s misrepresentation of her racial background, a new report on multiracial identity in the United States suggests that more and more Americans will, in some ways, play a more active, deliberative role in defining their racial identities.

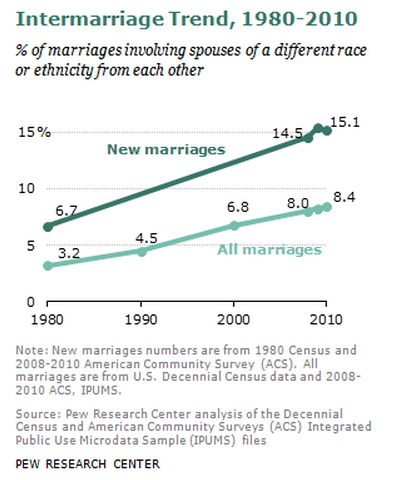

This is simply a matter of demographics, according to research. A new report from the Pew Research Center entitled “Multiracial in America” suggests that the population of Americans with at least two races in their background, currently at a high of 6.9 percent, is growing three times faster than the rest of the U.S. population. This fits with trends identified by the U.S. Census Bureau, which saw a spike from 6.8 million in 2000 to nine million in 2010—that’s 32 percent—in the number of Americans who checked more than one race on their census forms. In addition, Pew reported in 2012 that some 15 percent of new marriages in 2010 were interracial, more than double the share in 1980.

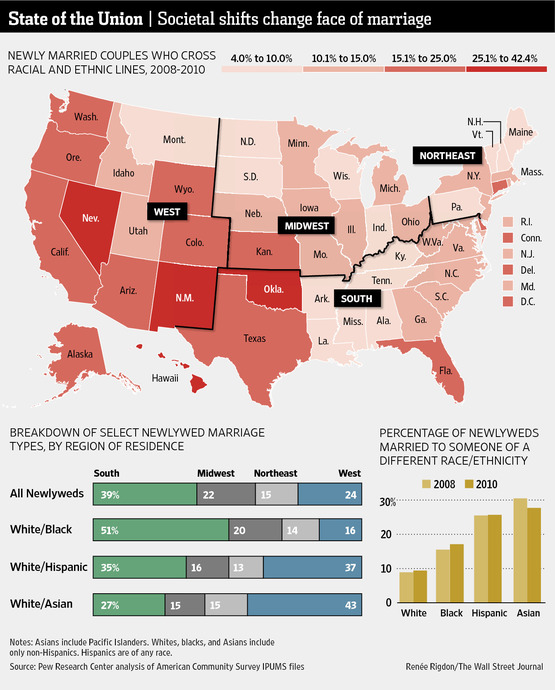

This should be obvious. After all, approval of interracial marriage jumped from four percent in 1959 to 87 percent in 2013 (Loving v. Virginia made interracial marriage bans illegal in 1967). Below, the Wall Street Journal lays out how interracial marriage has changed the face of American society:

This in itself has little bearing on Dolezal’s fraud, but Pew identifies an important trend: Multiracial adults “cannot be easily categorized.” For multiracial Americans, there’s far more fluidity in racial identity. Despite the fact that 61 percent of multiracial Americans don’t actually identify as “multiracial,” about 30 percent of the subjects in Pew’s research say that they have “changed” the way they talk about their racial identity over the course of their life—and often, from situation to situation. While “passing” as a different race has a long history in the U.S., particularly in African Americans seeking to avoid racial discrimination, Pew suggests that the practice now seems like an integral part of the multiracial experience.

While Rachel Dolezal outright lied to friends and colleagues about her background and circumstances, her fraud shines a light on the fluidity and complexity of race. Dolezal isn’t black by “by lineage or lifelong experience,” as the New Yorker‘s Jelani Cobb puts it—but what else is blackness, then? Does blood matter? Is blackness, or any race, really, performative? These are the questions that, ironically, are going to afflict a growing portion of Americans for generations to come. Is the strange saga of Rachel Dolezal not the perfect pedagogical tool for examining the intricacies of race and privilege?

The strangest part of the Rachel Dolezal saga is that she may be a sign of things to come.

While 60 percent of Pew respondents say they are “proud” of their identity, life doesn’t always give them the pleasure of that experience. Passing for multiracial Americans may even be a measure of personal identity. According to Pew, many multiracial adults with black backgrounds “have a set of experiences, attitudes and social interactions that are much more closely aligned with the black community”—not because they sought those experiences out, but because 69 percent say “most people view them as black or African-American.” By contrast, biracial white and Asian adults “feel more closely connected to whites than to Asians,” by the same principal.

The irony, of course, is that the “average American” of the future won’t be easily pigeonholed into a racial category based on appearance. In October 2013, National Geographic hired renowned portrait photographer Martin Schoeller to capture the faces of America’s multiracial future. The results are astounding, and quite telling. “In today’s presumably more accepting world, people with complex cultural and racial origins become more fluid and playful with what they call themselves,” writes Lise Funderburg. “On playgrounds and college campuses, you’ll find such homespun terms as Blackanese, Filatino, Chicanese, and Korgentinian.”

In reality, the future of America may be one where, transmuted by the demographic and anthropological currents of history, racial identity becomes something determined by choice and desire, rather than centuries of structural forces—and their corresponding privileges and burdens. And as race becomes increasingly fluid, the results may yield less and less anxiety about not just who’s white and who’s black, but who gets to “make” those distinctions in the first place. As sociologist Nikka Khanna told Pacific Standard: “Race isn’t real, but we make it real. We attach meaning to what it means to be black or white or Asian in our society, and because of that we oftentimes police the boundaries of different racial groups, about who belongs and who doesn’t belong.”

Make no mistake: Rachel Dolezal deceived her colleagues about her personal background, regardless of the remarkable and important work she did as a member of the NAACP, or, more importantly, the fact that she self-identifies as black. But the general lesson of her years-long deception—that race isn’t genetic, but a social construct dictated by centuries of history—is oddly salient for a generation of Americans more politically, culturally, and ethnically diverse than any in history. The questions of race and identity posed by the Dolezal saga are ones multiracial Americans have experienced for at least a generation, and ones that the next generation will have to grapple with as well—it’s just a shame that the impetus for this conversation had to come from the strange story of a single woman.