The New York Times recently ran a story describing the Savannah, Georgia, defenders of Paula Deen. Deen, of course, is the recently disgraced television chef who was fired by the Food Network due to her admissions of casually using racial slurs and planning an antebellum plantation-themed wedding for her brother. The Times’ story is laden with quotes from a number of white Southern patrons of Deen’s restaurant offering defenses of their region and some barbs for their Northern critics. For example,

“Everybody in the South over 60 used the N-word at some time or the other in the past.”

“I don’t understand why some people can use [the N-word] and others can’t.”

“We have lived with each other and loved each other here for a long time. Sometimes I think there is more prejudice in the North than there is in the South.”

So what’s the story? Few would question that the South was home to some of the world’s most virulent white racism just a few decades ago, but similarly, few would doubt that the region has made tremendous strides to overcome that legacy. Is there still more prejudice in the South than in the North?

Political scientists and pollsters used to have an easier time identifying bigots in surveys; Americans were once very upfront about their discomfort, distrust, and even hatred toward people of other races. Over the past half century or so, though, a social desirability effect has become apparent. Even if a person fundamentally dislikes members of another race, he knows not to say this publicly, or even in response to a private survey. It’s simply not part of the acceptable parlance any more. But that doesn’t mean racial animus has disappeared.

Political psychologists instead look for evidence of “symbolic” racism. These are instances of individuals using code words that tend to indicate racial animus without being overtly racist themselves. For example, a white person might complain about immigrants, welfare queens, food stamp recipients—populations that are disproportionately racial minorities and portrayed as unjustly taking something from other Americans—but still deny that they have any problem with non-whites. (For a rich example of this, see Newt Gingrich’s exchange with Juan Williams during the 2012 Republican presidential primary debates.) Oh, and if you’re complaining that you aren’t allowed to use the N-word while other people get to? You just might be a symbolic racist.

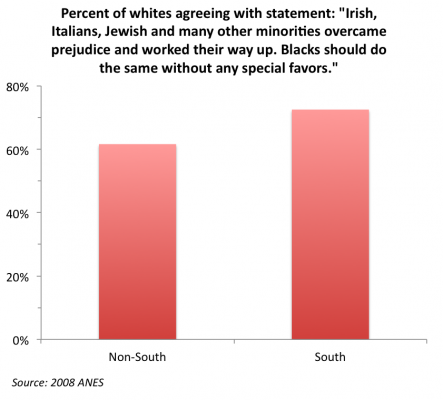

So here’s an example of a question along these lines from the 2008 American National Election Studies, asking whether African Americans should be “working their way up” without “special favors.” Only the white respondents are included in the tally:

There’s about a 10-point difference there, with Southern whites more likely to agree with the question than non-Southern whites. We see the same sort of pattern when we look at questions about interracial marriage, whether blacks should “push themselves where they’re not wanted,” or whether the law should support homeowners who choose not to sell their house to blacks. Southern whites are consistently more likely to choose the symbolically racist answer than non-Southern whites are.

In a thorough review of these sorts of questions and how they vary by geography, Nicholas Valentino and David Sears (via John Sides) concluded the following:

General Social Survey and National Election Studies data from the 1970s to the present indicate that whites residing in the old Confederacy continue to display more racial antagonism and ideological conservatism than non-Southern whites. Racial conservatism has become linked more closely to presidential voting and party identification over time in the white South, while its impact has remained constant elsewhere. This stronger association between racial antagonism and partisanship in the South compared to other regions cannot be explained by regional differences in nonracial ideology or nonracial policy preferences, or by the effects of those variables on partisanship.

In other words, it’s not just that there’s more prejudice in the South; Southerners are more likely than Northerners to use that prejudice in making political decisions.

This, of course, is not to suggest that the North is free of prejudice or that the South is peopled solely by bigots. And it is not to disparage the considerable racial progress the South has made since the era of segregated schools and violent repression of the vote, which happened within the lifetime of many of its residents. But even with all that progress and all the movement of people into and out of the region over the past half century, key cultural differences do remain. A future Paula Deen could emerge in the North. But she’s far more likely to emerge in the South.