In the months after my grandfather died, no one ever seemed to notice how much time I was spending in the bathroom. The grown-ups were always downstairs in the den talking about who we were related to and how, and my sister was always somewhere occupied with the toys that had been cobbled together at the big old house for us: Pik-up-Stix, a peeling Rubix cube, our father’s childhood picture book about time with a built-in clock, its metal hands rusted and dagger-sharp. I was nearly 11, nearly bored of those things. It was a relief to sit alone behind the locked door at the top of the stairs. No one called up to me, no one knocked or pried; I was not the family’s most notable absence.

My grandfather had been a big man, taller than my own tall father and more loosely hewn. He took up a considerable amount of space in a few particular places: At the head of the dining room table, in the front seat of his green pick-up, in a gray suit atop one of his long-striding horses, but mostly in the den in his red leather armchair. After he got sick, around Christmas, a bed was moved down to the den for him but I never saw him in it. For as long as he lay there I avoided the room. Every time I hurried past the doorway, my eyes would lock on his empty chair, red and sagging. Two weeks past New Year’s, he was gone.

If anyone had taken note of how often and for how long I was shutting myself away they may have sensed cause for concern, and they may have been right about the need for concern but not about the cause. I took every vague twinge in my gut as an excuse to turn the lock and install myself on the toilet, but it was not a matter of digestion. I was reading. For as long as I’d been literate I’d rarely gone anywhere without a book-shaped thing, and in a pinch I could have pulled anything from the slumping heaps of books and magazines all over the house, and I could have read any of these things anywhere. But there was something different, something more alluring, about the copies of Reader’s Digest stacked in the basket in the bathroom at the top of the stairs.

Almost every time I walk out of a house, or watch someone walk out of a house, I wonder if this will be the last time, and for which of us. I’m never sure if I’m buying myself time or spending it.

At some point, based on reasoning I can’t access now, I had sensed that these magazines were not supposed to be read by a child, or at least not by me. I was not a drawer-rifler, not an early peeper of Christmas presents; I was very aware of the general pattern of things that I was and wasn’t supposed to do, and I lived my small life accordingly. But in a rare deviation I simultaneously decided that these magazines were off-limits and that I would, in fact, be reading them. And so I did, sitting on the toilet, my pants pooled around my ankles on the cool white tile, the world beyond and below shuffling on without me.

At 11, I had already been fixated on the eventuality of my own death for half my life. Now I was coming to understand that the years that stretched between me and my unavoidable end were full of much else to fear—complications, malfunctions, things maybe even worse than death in all their unpredictability. Reader’s Digest did not disabuse me of this notion. Each squat little issue was filled with talk of cholesterol and blood clots and diabetes and heart disease. There were new ideas every month about what you should or should not eat to keep every new threat at bay, and ads for diseases I’d never heard of that listed side-effects that sounded worse than any disease I ever had heard of.

Reader’s Digest had answers, too, but they mostly coalesced into a frantic clatter: diet tips and exercise tips and tips on when to worry about your body changing colors or shapes or your arm tingling or your head aching, tips on when to heed tips and when not to and who should you trust? Your doctor? That other doctor? Sometimes doctors don’t know, but other doctors might, but all doctors can be wrong. There were so many routes by which I might meet my eventual death, and so many horrible detours to take before I got there. I’d had no idea. But Reader’s Digest did.

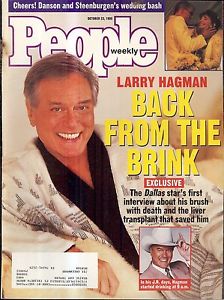

During one visit to the bathroom I found a new magazine in the basket, an issue of People with a bathrobed, Chiclet-toothed Larry Hagman on the cover. Big yellow letters declared him BACK FROM THE BRINK and smaller yellow letters stage-whispered that inside could be found the Dallas star’s first interview about his brush with death and the liver transplant that saved him. I found this strange, as I’d heard he’d been shot. My grandfather had died of something to do with his liver, too, and there had been no attempt that I knew about to bring him back from any brink. I read the Larry Hagman story, and the one about Ted Danson and Mary Steenburgen’s wedding, but People wasn’t what I wanted. It was floppy and breezy and starry-eyed. I needed squat and dense and serious, grim diagnoses and words I couldn’t pronounce. I needed Reader’s Digest.

I had favorite issues of the magazine and, if necessary, would unload the basket’s entire contents on the tile floor to pull them from the chaff. One was so old its cover wasn’t glossy full-color but light-green cardstock, all the pictures inside powdery grayscale. Inside was the story about a boy around my age whose doctors found a tumor growing all up and down his spine. His only chance to avoid total paralysis was a risky new surgery in which the surgeons would lay him out on a table and slice his back open and scrape the tumor away from his vertebrae until it was all gone. His mother, who told the story to the magazine, was distraught: He had recently started taking violin lessons and showed real promise, she said, but if the surgery went wrong he might never play again—he might never do anything again. In the end, the boy’s surgery was a success and he made a full recovery and resumed his violin lessons and the rest of his life, and somehow this always surprised me.

Every issue of Reader’s Digest arrived with the implied promise of one of these as-told-to, real-life tales of survival. There was a new spine-boy every month. If it wasn’t a tumor it was a birth defect, a rare virus, a freak household accident. The idea was for the teller to wring some sort of lesson or wisdom from the gray rag of their grief and pass it along to the magazine’s readers, an apparently parched demographic. And I suppose, for a while, I was among them.

Every time I read and re-read about spine-boy, I pictured an image of a tumor growing up my own back, pink like Silly Putty around the tiny white knobs of my spine. And I felt great shame that if this or any other terrible fate befell me I wouldn’t have even the most basic mastery of a violin or any other special thing to claim as my life’s main achievement, or to return to if I recovered. What would I have? Not much: A carefully guarded sticker collection, a shoebox of tourist-trap brochures culled from every hotel lobby I’d walked through, a lockless diary in which I had recently excoriated my mother for not letting me watch Nightmare Before Christmas. (I couldn’t understand what she meant when she said it was “too deathly” for me, that I “didn’t do well” with those things.)

I’m not sure what our last goodbye was like. If I’d had any idea that it would be the last one—if I’d had any idea, then, that any goodbye could be the last one—I can’t say it would have been any different than what it was.

When I would flip open that issue of Reader’s Digest and come across spine-boy I always felt a shivery stomach-flop of recognition. But another story in another issue hit me like a wave of dread—like when the hot water cuts out in the middle of a shower. The story was in a more recent, full-color issue: A father remembering the morning he spent watching his wife and kids hurrying around to get ready to leave the house on their way to work and school—all of them running late, so late, no time for breakfast, no time for even a kiss goodbye. He described watching his family pile into the car and watching the car zoom away down the street, not knowing it was the last time he would watch them do anything. Minutes later, out on the interstate, they were crushed by a runaway tractor-trailer. Wife, kids, all of them dead.

I could never make myself remember which issue that story was in and so could never make myself avoid it. It lurked in the basket like a viper. All it took to devastate me was a flash of passages as I flipped through: the cheery illustration of a station wagon in a driveway, the inset snapshot of the family in happier times. I knew it could be inside every stout glossy copy I picked up, but I kept reading anyway, or maybe because.

What the man with the dead family had learned was something about the preciousness of life, slowing down and appreciating the time you have with the people you love, because they might rush out that front door and never come back. But I was more struck by the cruelty of timing. The man said something about the collision being “a matter of seconds”—I remember those words—and about how his family might still be alive if they had been in less of a hurry, how he might have saved them by helping them go about their morning in a more leisurely, loving way. But if it really was just a matter of seconds, I thought, couldn’t they have been spared by being in more of a rush? Was it possible that they were not harried enough? How could you ever know if you were rushing too much or too little? How could you know until the thing you didn’t even know you were trying to avoid was right there, bearing down upon your helpless self?

Even now, 20 years later, I catch myself dawdling before I leave the house in the morning or before I leave the office at night. I adjust and re-adjust my sleeves inside my jacket, take the long way to return my grocery cart, stare at myself in the bathroom mirror until it starts to feel ridiculous. Almost every time I walk out of a house, or watch someone walk out of a house, I wonder if this will be the last time, and for which of us. I’m never sure if I’m buying myself time or spending it.

These are ghastly habits, but ones I haven’t quite convinced myself are worth trying to break. I rarely manage or even try to capture anything about those parting moments, anything that might be useful to replay if my worst suspicion comes true. I tell myself maybe that’s the point—to appreciate the ordinariness, to make peace with the very real potential for imperfect final exchanges. Because if it’s not a rushed morning and a runaway tractor-trailer, if it’s not a blood clot or a gunshot, it will eventually be something else.

For years I was wrong about how my grandfather died. It wasn’t his liver but his pancreas, or more precisely, the cancer that planted itself there and bloomed faster than any of us could catch a breath. But his liver would have done the job if given more time. I’m not sure what our last goodbye was like. If I’d had any idea that it would be the last one—if I’d had any idea, then, that any goodbye could be the last one—I can’t say it would have been any different than what it was. I was a child and afraid, my eyes locking on the empty red chair, my fingers twisting the lock of the bathroom door, shutting myself away before I could be invited in.

I would lose all sense of time up in the bathroom, pantsless and bent double. But after a while the ache would come, the blurred pain radiating from my lower back and the needles inside my legs. I would entertain a self-diagnosis of acute coincidental spinal tumor before snapping back to myself and my dangling feet, my hunched shoulders, the skin of my backside fused to the toilet’s maw. Only then would I peel myself away and bury the Reader’s Digests deep in the basket again. I would flush the empty bowl and pantomime a hand-washing ritual, then turn the lock and pry open the door. And then it was back to life, back again downstairs into the waiting world, to see what I had missed.

The Weekend Essay is a Saturday series edited by Leah Reich.