Many critics are praising 12 Years a Slave for its uncompromising honesty about slavery. It offers not one breath of romanticism about the ante-bellum South. No Southern gentlemen getting all noble about honor and no Southern belles and their mammies affectionately reminiscing or any of that other Gone With the Wind crap, just an inhuman system. 12 Years depicts the sadism not only as personal (though the film does have its individual sadists) but as inherent in the system—essential, inescapable, and constant.

Now, Noah Berlatsky at The Atlanticpoints out something else about 12 Years as a movie, something most critics missed: its refusal to follow the usual feel-good cliche plot convention of American film: “If we were working with the logic of Glory or Django, Northup would have to regain his manhood by standing up to his attackers and besting them in combat.”

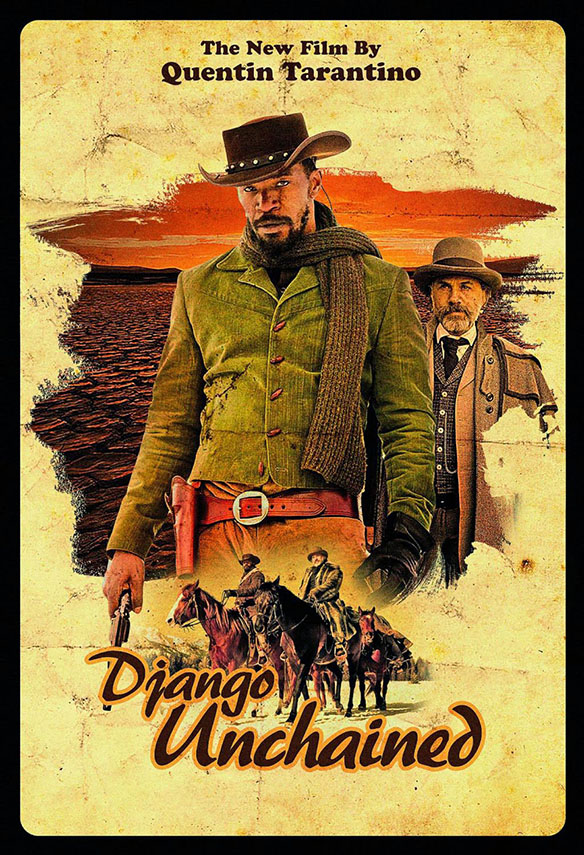

Django Unchained is a revenge fantasy. In the typical version, our peaceful hero is just minding his own business when the bad guy or guys deliberately commit some terrible insult or offense, which then justifies the hero unleashing violence—often at cataclysmic levels—upon the baddies. One glance at the poster for Django, and you can pretty much guess most of the story.

It’s the comic-book adolescent fantasy—the nebbish that the other kids insult when they’re not just ignoring him but who then ducks into a phone booth or says his magic word and transforms himself into the avenging superhero to put the bad guys in their place.

This scenario sometimes seems to be the basis of U.S. foreign policy. An insult or slight, real or imaginary, becomes the justification for “retaliation” in the form of destroying a government or an entire country along with tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of its people. It seems pretty easy to sell that idea to us Americans—maybe because the revenge-fantasy scenario is woven deeply into American culture—and it’s only in retrospect that we wonder how Iraq or Vietnam ever happened.

Django Unchained and the rest are a special example of a more general story line much cherished in American movies: the notion that all problems—psychological, interpersonal, political, moral—can be resolved by a final competition, whether it’s a quick-draw shootout or a dance contest. (I’ve sung this song before, most recently here after I saw Silver Linings Playbook.)

Berlatsky’s piece on 12 Years points out something else I hadn’t noticed but that the Charles Atlas ad makes obvious: It’s all about masculinity. Revenge is a dish served almost exclusively at the Y-chromosome table. The women in the story play a peripheral role as observers of the main event—an audience the hero is aware of—or as prizes to be won or, infrequently, as the hero’s chief source of encouragement, though that role usually goes to a male buddy or coach.

But when a story jettisons the manly revenge theme, women can enter more freely and fully: “12 Years a Slave though, doesn’t present masculinity as a solution to slavery, and as a result it’s able to think about and care about women as people rather than as accessories or MacGuffins.”

Scrapping the revenge theme can also broaden the story’s perspective from the personal to the political (i.e., the sociological): “12 Years a Slave doesn’t see slavery as a trial that men must overcome on their way to being men, but as a systemic evil that leaves those in its grasp with no good choices.”

From that perspective, the solution lies not merely in avenging evil acts and people but in changing the system and the assumptions underlying it, a much lengthier and more difficult task. After all, revenge is just as much an aspect of that system as are the insults and injustices it is meant to punish. When men start talking about their manhood or their honor, there’s going to be blood, death, and destruction—sometimes a little, more likely lots of it.

One other difference between the revenge fantasy and political reality: In real life, results of revenge are often short-lived. Killing off an evildoer or two doesn’t do much to end the evil. In the movies, we don’t have to worry about that. After the climactic revenge scene and peaceful coda, the credits roll, and the house lights come up. The End. In real life though, we rarely see a such clear endings, and we should know better than to believe a sign that declares “Mission Accomplished.”

This post originally appeared onSociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site.